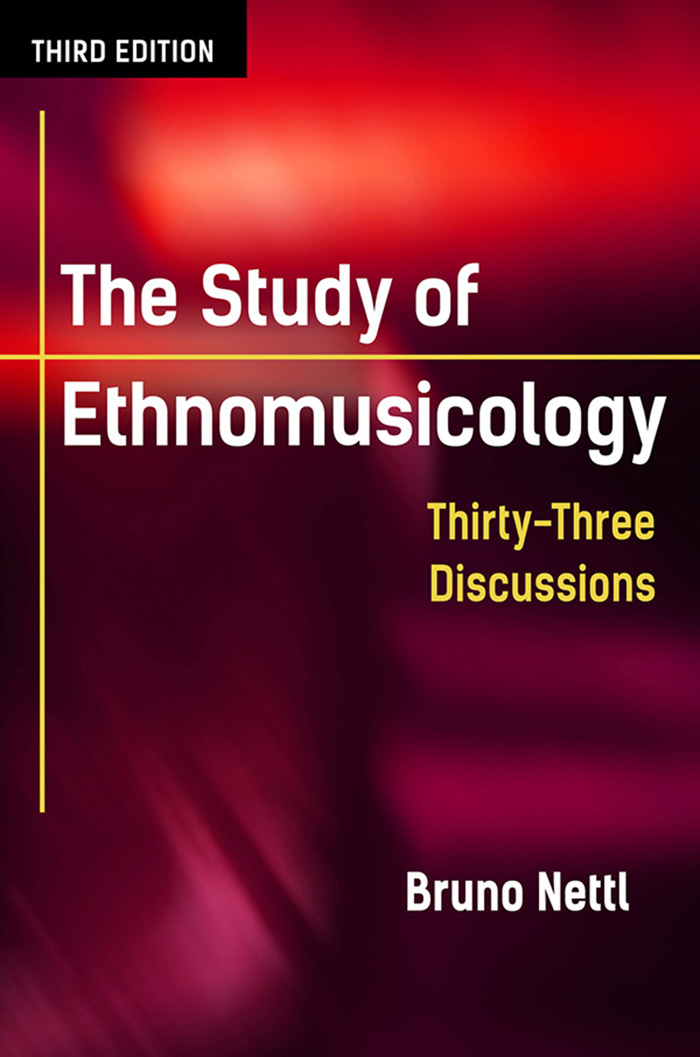

The Study of Ethnomusicology

THIRD EDITION

The Study of

Ethnomusicology

Thirty-Three Discussions

THIRD EDITION

BRUNO NETTL

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2015 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nettl, Bruno

The study of ethnomusicology : thirty-three discussions / Bruno Nettl. Third edition.

Pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03928-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-08082-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09733-1 (e-book)

1. Ethnomusicology. I. Title.

ML3798.N47 2015

780.89dc23 2014043248

edition supported by a grant from

Figure Foundation

crosswords of music true illumination

For Wanda

(the lady of my life)

Contents

Preface

I am happy to present my third attempt, brought up to date, hopefully improved, and substantially enlarged, to provide an account of ethnomusicology as a field of research. The reader acquainted with the earlier editions will note a good many changes. When I began this project in 1979, I barely considered myself a mature scholar, and the field of ethnomusicology was still struggling for its place in the academy. Now, some thirty-five years later, ethnomusicology is thoroughly established (though not universally understood), and I see myself looking back at sixty years in the profession, to having worked in a field whose history now extends well over a century. Ethnomusicology has changed substantially even since I undertook the second edition, about 2002. In this third edition of The Study of Ethnomusicology, I have tried to describe much of what has happened recently, but to do this in the context of its past. My attitude is not so much that of Look, weve got something brand new, as of an understanding that the things we believed and did were valuable and valid, but we have had to change and redirect.

So, whats new? To begin with a minor matter, Ive changed the subtitle from Issues and Concepts to Discussions. I still believe that one way of defining a field of scholarship is by the problems that its practitioners face and the issues about which they argue. But I realize that these issues are not really separable and that certain ones, such as the insider-outsider dyad, the concept of culture, the various taxonomies of music, keep recurring and that it is therefore best to see these chapters as discussions.

Each of the chapters has been rewritten, and I discuss and comment on some of the voluminous literature that has appeared during the twenty-first century. The bibliography has been enlarged by some 10 percent. Several chapters of the second edition have been reduced and their content combined with others. On the other hand, I have been able to give increased attention to the study of change, the understanding of minorities, the relationship of ethnomusicology to other disciplines, the practice of ethnomusicology in newly developed nations, the history and use of recordings, the importance of popular music, and the matter of ownership and control of music. Ive had to take second and third looks at certain issues such as the origins of music, the relative significance of the system of ideas about music as against the understanding of musical style for comprehending a musical culture, the significance of performance study, and the role of the concept of authenticity. At the same time, less space is devoted to some subjects, as, for example, universals, conjectural history, and tune relationships. I have eschewed a narration of the entire history of the field, but the fundamentally historical orientation of each chapter remains.

The arrangement and order of the chapters have been reorganized a bit, and there are now six groups of chapters. I have added a section of five new (or newish) chapters titled From a Broad Perspective. Some of these final chapters include materials, revised, from my books Encounters in Ethnomusicology (Harmonie Park Press, 2002) and Nettls Elephant (University of Illinois Press, 2010). They are devoted, respectively, to the newly developed field of applied ethnomusicology, to the relationship of ethnomusicology to other disciplines, to my need to confess to some second thoughts and even U-turns in my perceptions and earlier interpretations, to a personal (and hopefully lighthearted) account of certain aspects of the history of our field, and, finally, to an attempt to provide a snapshot of the present state of ethnomusicology, which also tries to reply to a question I have been pondering for a few years, a query put to me by a scientist: What are the great discoveries of your field?

And whats old? This makes no pretense at being a new book; its still, in its essence, the work that began to be known as the red book among some students. I have tried to keep the informal style of presentation and the occasional bit of humor. The basic structurebrief essays with short subdivisionsremains. I have tried to maintain balance between objective description of what has happened or is happening and my personal view of the past and present of ethnomusicology. By the same token, I continue to balance illustrations from the accounts of many scholars with a substantial amount from my own, sometimes recent, experience. But as the field has progressed and aged, so I too am writing, hopefully, as a slightly wiserbut fortunately not much sadderauthor.

* * *

It goes without saying that I have benefitedin both the preparation of this work and what Ive had to study to be able to undertake this preparationa great deal from many colleagues, friends, and students. I can mention only the most prominent. Im very grateful (in no particular order) to Tom Turino, Vicki Levine, Phil Bohlman, Steve Blum, Dan Neuman, Chris Goertzen, Albrecht Schneider, Zuzana Jurkov, Steve Slawek, Alison Arnold, Tony Seeger, Stefan Fiol, Ted Solis, and Ellen Koskoff. All of them have made suggestions that ended up being quite specific to this project, gave me food for thought, shot down some goofy ideas, and encouraged mein some cases already in the preparation of the first edition. Im also grateful to Bill Kinderman, Sally Bick, Anna Maria Busse Berger, Gabriel Solis, Theresa Allison, Victor Grauer, and Harry Liebersohn for stimulating discussions and correspondence.

I wish to thank Donna Buchanan, my colleague in the Division of Musicology at the University of Illinois, for discussing issues in the area of social theory and for sharing her syllabus for a seminar on this subject. I very much appreciated the willingness of my daughter Rebecca Nettl-Fiol, professor of dance at the University of Illinois, to read and comment on the sections on dance research. And I am grateful to Aniruddh Patel, professor of psychology at Tufts University, for valuable advice on recent literature (some by himself) on the origins of language and music.

I continue to feel gratitude to many who were helpful to me in preparing the first edition. These I cannot mention here for lack of space, but they include many colleagues at the University of Illinois and, very significantly, a number of my teachers in the course of my fieldwork over the decades going back to 1950, several of whom are mentioned in the course of these pages. I wish particularly to honor Judy McCulloh, who passed away as this manuscript was being edited, my friend for fifty years and longtime editor for the University of Illinois Press who encouraged and aided the publication of the first and second editions of this work.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.