Contents

About the Book

In 1973, aged twenty-two, Timothy OGrady left America for Europe. He had grown up through the time of moonshots and protest marches, new music and unprecedented economic expansion and of hopes for a new society, a new democracy and a new kind of man.

For the next thirty years he lived in and wrote about Europe. As he did, the American counter-culture crashed, Ronald Reagan came and went, wars were declared and the country was attacked by air. Much of the world began to look at America in a new way, wondering what had happened to it and where it was going. Among them was Timothy OGrady, and he decided to go back and investigate.

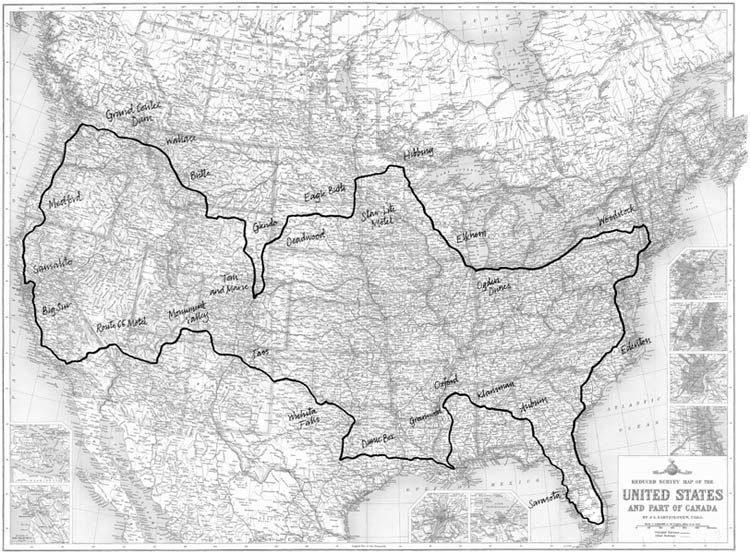

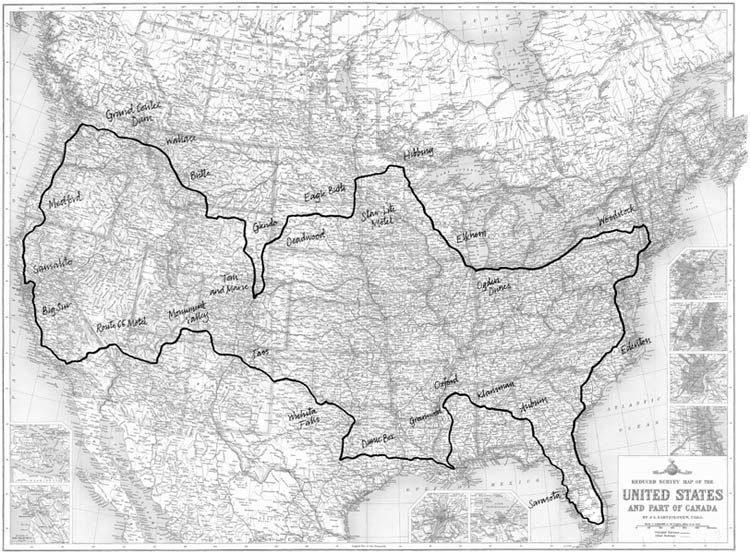

Following in the footsteps of such Europeans as de Tocqueville, Dickens and Simone de Beauvoir, and such Americans as Henry Miller, Kerouac, Steinbeck and Woody Guthrie, he went out onto the American road, travelling over fifteen thousand miles through thirty-five states. He met academics, the homeless, war veterans, political activists, New Orleans rappers, billionaires, novelists and a Ku Klux Klansman. A Yale legal historian told him why there are a million lawyers in America, a Chicago broker how executive pay is set and how the lobbying system works in Washington, and a Salvadorean gang member how life is on the streets of East Los Angeles. In every bar he stopped in, it seemed, there was a story of American life to be heard.

Using history, memoir, state-of-the-nation analysis and a novelists skill at evoking places and people, Divine Magnetic Lands presents a picture of America as it evolved and how it is at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

About the Author

Timothy OGrady was born in the USA and has lived in Ireland, London and Spain. He is the author of the novels Motherland, which won the David Higham award for best first novel in 1989, I Could Read the Sky, which won the Encore award for best second novel of 1997 and Light. His book On Golf was published by Yellow Jersey to superb reviews in 2003.

ALSO BY TIMOTHY OGRADY

Fiction

Motherland

I Could Read the Sky

(with photographs by Steve Pyke)

Light

Non-fiction

Curious Journey: An Oral History of Irelands Unfinished Revolution

(with Kenneth Griffith)

On Golf

for Eduardo and Beatriz OGrady

Come, I will make the continent indissoluble,

I will make the most splendid race the sun ever shone upon,

I will make divine magnetic lands,

With the love of comrades,

With the life-long love of comrades.

Walt Whitman, For You O Democracy

God save America! Thats what I say too, because who else is capable of doing the trick?

Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

Map Royal Geographical Society, London

Introduction

When I was a child I had a feverish dream. I was in an open field on a low wooden stage, American flags draped in pendulous crescents across the front, a military band standing by. White clouds rolled and churned in the air as though boiling in vats. Men in suits and hats sat on the stage, others stood with women in the field. I was on a box making a frantic speech amid all this Americana that seemed to be from the era of steam trains and Abraham Lincoln.

I was around nine years old at the time. I had bronchitis and a temperature of 104 degrees. During the afternoon my mother had put me to bed in her and my fathers bedroom in order to keep an eye on me. This is where the dream came upon me. Some time in the early evening she heard a shout and came in to find me standing on her bed, sweat running down my face and soaking my pyjamas, my arms upraised and a tormented expression on me as I called out, EVERY MAN SHOULD BE PRESIDENT ! It was the end of a long thought, and seemed the most urgent thing that had yet happened to me.

Where had the dream come from? Countries tend to be made of conglomerations of personages and events, clashing and flowing together as time moves on. From any point their pasts are visible to their people pasts made of the evolution of language and customs and diet and of ill- or well-accomplished attempts at fiscal control and the maintenance or gaining of power. An individual may be dwarfed by the vast scale of this past, but he feels too an intimacy with it. Its things are well worn and familiar.

America is different. From the Puritans on, America has presented itself as an abstraction, born fully formed in an instant. It is made and ever remade by people who throw off their pasts upon arrival and begin at Ground Zero, their eyes fixed brightly on the future. If they navigate with skill they can get to the Promised Land. America is an experiment, a revelation, the place elected by God to be an example to the world. It lives in a continuous present of the invention and reinvention of the ill-fitting and sometimes contradictory concepts of absolute liberty and absolute equality. These concepts were proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence, worked out in terms of the architecture of government in the Constitution and guaranteed in the Bill of Rights. The rest for most is cartoon or waxworks or theme park. Americans are generally not very interested in their history. It has no tangibility for them. They are interested in the wondrous now. Liberty and equality do not evolve. They simply are. The America that is defined by them is not a process, but is rather an idea set out in philosophical tracts that grabs its people, enters their subconsciousnesses and becomes their point of reference for things both political and personal.

In his preface to Leaves of Grass Walt Whitman writes with a breathless, stuttering awe of the wonder of his nation and of what qualities a poet must have in order to rise to the occasion of writing about it. In the history of the earth hitherto, he writes, the largest and most stirring appear tame and orderly to [the United States] ampler largeness and stir. Here at last is something in the doings of man that corresponds with the broadest doings of day and night. Here is not merely a nation but a teeming nation of nations The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. He writes of Americas rivers and the blue breadth of its inland sea, its trees and mines and pasturages, the songs of its birds, its wharf hemd cities and superior marine, its rapid stature and muscle, the haughty defiance of its Revolution and its long amativeness and of how the poet must incarnate it all in its variety and breadth as he tries to write the great psalm of the republic. He will find its tone, its vocabulary and its meaning in the people themselves, for in America as in no other place the nation and the people are one. Other states indicate themselves in their deputies, but the genius of the United States is not best or most in its executives or legislatures, nor its ambassadors or authors or colleges or churches or pastors, nor even in its newspapers or inventors but always most in the common people. Their manner speech dress friendships the freshness and candour of their physiognomy the picturesque looseness of their carriage their deathless attachment to freedom their aversion to anything soft or mean the fierceness of their roused resentment their curiosity and welcome of novelty their susceptibility to a slight the air they have of persons who never knew how it felt to stand in the presence of superiors These too, says Whitman, are unrhymed poetry.