An imprint of Globe Pequot

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 by Charles Pappas

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pappas, Charles, 1956- author.

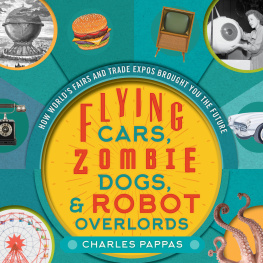

Title: Flying cars, zombie dogs, and robot overlords how worlds fairs and trade expos changed the world / Charles Pappas.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Lyons Press, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017023032 (print) | LCCN 2017015166 (ebook) | ISBN 9781630762391 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781630762407 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: ExhibitionsHistory.

Classification: LCC T395 .P275 2017 (ebook) | LCC T395 (print) | DDC 607/.34dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017023032

Printed in Malaysia

This book is dedicated to everyone Ive met over the last decade who thought the topic was as fascinating as I do. Wow, are you ever messed up.

No book is an island. This one could not have been built without the talents of journalist, essayist, scuba diver, pirate-treasure hunter, and tattooed cat-hoarder Cynthya Porter, whose contribution could be likened to offering life vests on the Titanic . Her prose is sharp enough to shave with, smooth enough to give Teflon a run for its money, and as hard to resist as cookie dough. But not the kind you get E. coli from.

Now for some obligatory sucking up. I need to thank Travis Stanton, Randy Acker, Lee Knight, and the crew of Exhibitor magazine for giving me time, leeway, encouragement, and a paycheck. And Travis, thanks for the Chinese fortune cookie years ago that set all of this into motion.

Last, to my agent Malaga Baldi, whose patience and kindness with her writers are exceeded only by her belief in them.

Contents

Introduction

Every time you chew a stick of Juicy Fruit, eat a hamburger, slip on a nylon, plug your phone into a wall socket, flick on a TV, withdraw money from an ATM, lick an ice-cream cone, switch on a computer, ride an escalator, play a DVR, watch a movie about dinosaurs, or pop a tranquilizer, youre doing something that originated or was popularized at a trade fair or worlds fair.

In fact, each new technology and every novel product that rocked America and rolled the world, from the Colt revolver and the Corvette to fax machines and flush toilets, started at trade fairs, a $100 billion industry that includes world expos, trade shows, and state fairs.

To many, theyre as invisible as the oxygen in the air around us. But like an atmosphere, they surround and fill and permeate everything you know without you knowing it. More than just promoting material things, however, trade fairs evangelized every social movement and cultural concept, too, including Manifest Destiny, the closing of the frontier, Nazism, Fascism, eugenics, female suffrage, nudism, temperance, and technocracy. For every product and each dogma that blasted into mass popularity, its launch pad was a trade fair.

For hundreds of years, trade shows were as boring as the livestock, cloth, or herring they displayed on a rickety table or a reeking donkey cart. One of the earliestif not the earliestrecorded mentions of trade shows is in the King James version of the Bible, specifically Ezekiel 27:27, which dates back to around the sixth century BCE (Thy riches and thy fairs, thy merchandise...). Archaeological traces go back just as long: King Herod constructed a 3,200-square-foot exhibit hall near Jerusalem.

Things perked up in the twelfth century when the Crusades, needing infusions of money, tapped newly created town governments to fund their furious expeditions to the Holy Land. The Crusades ROI of silks, spices, and other goods fueled an increasing demand for these products, which businessmen in the fledgling governments supplied by setting up local marketplaces. With guarantees of safe passage from cooperatingand sometimes even warringroyalty, these medieval merchants traveled along a trajectory of French cities that included Provins, Lagny, and Troyes to show their wares in the marketplaces at outdoor fairs.

This fair system rapidly expanded to Ireland (at the Donnybrook Fair, exhibitors and attendees brawled so fiercely that the show became a byword for a fest of flying fists), Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany, where the shows convened, usually annually, near churches, and often on religious occasions, which guaranteed a ready-made audience. There the shows absorbed the Teutonic words for fair which comes from the Latin word feria, meaning a religious festival, and messe, which refers to the Latin term Missa, for religious services (which the Germans still use to name their trade shows). At these messe , merchants swapped or sold goods and even hired out servants. Fairs often specialized in one particular type of merchandise such as cloth, horses, or cattle, much as the International Consumer Electronics Show (CES) focuses on electronics and the Kitchen & Bath Industry Show emphasizes homeware, centuries later.

It was a model that worked until it didnt. By the nineteenth century, industrialization had created an ever-expanding circle of markets whose material wants demanded satisfaction. It also saw the rise of B2Bbusinessmen began trekking to trade fairs not just to sell to consumers but also to offer samples to other businessmen, who came from faraway markets not by horse but by continent-traveling train and ocean-crossing ships. Show sponsorship passed from civil authorities to private ventures. The ability to mass-produce products put more emphasis on exhibiting new and improved goods, which in turn forced exhibitors to find new ways of displaying and demonstrating those very goods. To draw more customers, the shows attracted more exhibitors, who needed more time to hawk more products... to draw more customers.

The old system passed into history in 1851 at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations that ran in London from May to October. The first of the worlds fairs, it was conceived by Queen Victorias husband, Prince Albert, and its crown jewel was the Crystal Palace. Designed by Sir Joseph Paxton, the glass-and-iron exhibit hall ran over a third of a mile long and stretched more than one-and-a-third football fields wide, with a ceiling two-and-a-half times as high as the one in Chicagos McCormick Place convention center. From that moment on, worlds fairs became temporary fulcrums on which, for a few months at a time, the world teetered. Countries and cities alike used them as debutante parties to announce their arrival as superpowers or to vindicate their persistence as empires. For fairgoers, from London in 1851 to Shanghai in 2010, it was the political version of seeing the Beatles at Shea Stadium. Each of those expos was an alpha-male display of its host citys cultural muscle and sponsoring countrys economic potency. Each offered a vision of the future that was always deeply seductive and sometimes dangerously skewed. In all cases, the backing city and sponsoring country became masters of all they surveyed. They sold the gateway drug of products and technologiesphonographs, elevators, movies, TVs, PCs, ad infinitumthat would quickly go from being exclusive to being commonplace. The worlds fairs became a master plan, a mega-blueprint followed by every subsequent worlds fair and trade show.