Project Muse. - Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity

Here you can read online Project Muse. - Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Byzantine Empire;Iran;Middle East, year: 2012, publisher: Brandeis University Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity

- Author:

- Publisher:Brandeis University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- City:Byzantine Empire;Iran;Middle East

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Menahem Stern Jerusalem Lectures

Sponsored by the Historical Society of Israel and published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England

EDITORIAL BOARD

Prof. Yosef Kaplan, Senior Editor,

Department of the History of the Jewish People,

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem,

former chairman of the Historical Society of Israel

Prof. Michael Heyd, professor emeritus, Department of History,

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem,

former chairman of the Historical Society of Israel

Prof. Shulamit Shahar, professor emerita,

Department of History, Tel-Aviv University

FOR A COMPLETE LIST OF BOOKS IN THIS SERIES,

PLEASE VISIT WWW.UPNE.COM

G. W. Bowersock, Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World

Jrgen Kocka, Civil Society and Dictatorship in Modern German History

Heinz Schilling, Early Modern European Civilization and Its Political and Cultural Dynamism

Brian Stock, Ethics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western Culture

Fergus Millar, The Roman Republic in Political Thought

Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Later Roman Empire

Anthony D. Smith, The Nation in History: Historiographical Debates about Ethnicity and Nationalism

Carlo Ginzburg, History Rhetoric, and Proof

W hen the old antiquarian and polymath, Pliny, was registering the cities of the Near East in the fifth book of his Natural History in the middle of the first century CE, he remarked that in central Syria the great emporium at the Palmyra oasis lay between two powerful empires: inter duo imperia summa Romanorum Parthorumque (NH 5. 88). In other words, it lay between the Roman Empire and the Iranian Empire of the Parthians. Romes authority extended eastwards somewhat beyond Damascus, while the Parthians were in control as far west as the right bank of the Euphrates. But in the year 224 the Parthian Empire gave way to the empire of the Sassanians, who sought to revive the great Persian Empire of the Achaemenids. Only a century or so after that, Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople after himself. The city was, however, soon to be generally known as the New, or Second, Rome, or simply Rome, and consequently Yet, despite these colossal upheavals, the confrontation of superpowers that Pliny had so concisely formulated in the first century remained fundamentally unchanged. In the fourth century, as in the first, Palmyra, although now incorporated into a Byzantine province and home to a legionary detachment, still looked to two great empires, to the west and the east, one of Romans, or Byzantines, and the other of Iranians, now the Sassanian Persians.

Already in the third century the Sassanians had launched three devastating invasions to the west across Syria and Asia Minor. The havoc wrought by their armies left an open wound in the minds as well as the landscapes of the Romans at that time. To their military defeat was added the ultimate humiliation of the Persian capture of the Roman emperor Valerian in the summer of 260. When the Byzantine Romans took over the administration of the eastern Mediterranean lands, Persia remained as powerful a rival and threat as before, but with the conversion of Constantine to Christianity the confrontation of these two great powers was complicated by the establishment of a monotheist government in Byzantium in the face of the continuing dualism of Persian Zoroastrianism. The ambitions and animosities of both empires were accordingly reignited by religious zeal on both sides. Nature had long since dictated the main geographical area for Persias challenge to Rome, as Pliny had perceived. The territory at risk lay between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates River, which bounded the Sassanian realm, with its capital at Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. This vulnerable territory in the Near East included greater Syria, Palestine, Transjordan, Anatolia, and the nascent Christian kingdom of Armenia.

The fifth century saw new and more subtle ways for the Byzantines and the Persians to challenge each other, and to win allies for their rulers and religions. The internal dissent that arose among Christians after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 greatly complicated the role of the Romans of Byzantium, although Chalcedonians and Monophysites certainly could, and occasionally did, join forces when necessary. But new opportunities for forging alliances arose in late antiquity. Both Byzantium and Persia found it increasingly effective to lend their support to client peoples in marginal areas, where the conflict between the superpowers could be played out more remotely. Alliances of this kind were quite unlike the old Roman imperial habit of propping up dependent, or so-called client, kings in tiny principalities. The sheikhs of the Jafnid clan, the so-called Ghassnids, allied themselves with the Byzantine emperor, who thereby acquired influence in Syria, Palestine, and northern Arabia according to the shifting settlements and families of the clan. The sheikhs of the Narids, traditionally known as Lakhmids, forged links with Persia that brought Sassanian influence directly into the Arabian peninsula.

Even so, there had been no open conflict between the two superpowers in these regions until the Arabs of imyar, in the southwestern part of Arabia, provided the catalyst that brought in the empires of Byzantium and Persia, as well as the lesser but nonetheless expanding empire of Ethiopia as well. A surge of imperialist ambition on both sides of the Red Sea proved to be explosive, and it serves to open up an unfamiliar but immensely revealing window on late antiquity generally.being, fueled by a new religion that we know today as Islam.

Between the beginning of the third century and about 270, the pagan king (negus) of Ethiopia controlled an army that occupied parts of southwestern Arabia.

The titulature of the negus in the fourth century is known to us from the extensive epigraphy of Aezanas, or Ezana, whose inscriptions allow us to follow his career in some detail. He began as a great pagan ruler, claiming to be the son of the god Ares, who was equated with the Ethiopian Marem, and he ended as a devout Christian ruler who proclaimed that he owed his kingship to God. We can watch the whole process of conversion played out in the texts of his long inscriptions. The arrival of Christianity did nothing, however, to lessen the irredentist claims of the negus, even as he transferred his allegiance from Ares (Marem) to the Christian God. Quite the contrary. Ecclesiastical legend, and it may be no more than this, attributes the Christianization of Axum to a certain Frumentius from Alexandria, although the actual date of the conversion of Aezanas is irrecoverable. The inscriptions of Aezanas at Axum proclaimed his grandeur in no less than two languages and three scriptsEthiopic script (left to right) and Sabaic (right to left) for Geez, and Greek letters for Greek. These thereby encompassed the cultures of both sides of the Red Sea.

Stele of Aezanas discovered at Axum in May 1981, inscribed on the front, back, and right side. On the front, a text in Geez (classical Ethiopic), but written from right to left in the South Arabian (Sabaic) script, and beneath that a similar text in Geez, but written from left to right in unvocalized Ethiopic script, continuing on the right side. On the back, in Greek, is a comparable account of Aezanas and his achievements. Inscriptions published in Recueil des inscriptions de lEthiopie, vol. 1, nos. 185 bis (Semitic texts), 270 bis (Greek). Photograph courtesy of Finbarr Barry Flood.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

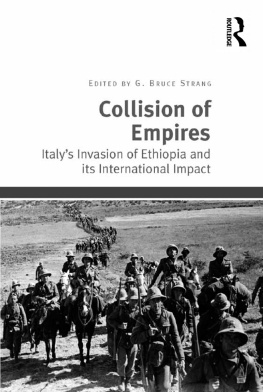

Similar books «Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity»

Look at similar books to Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.