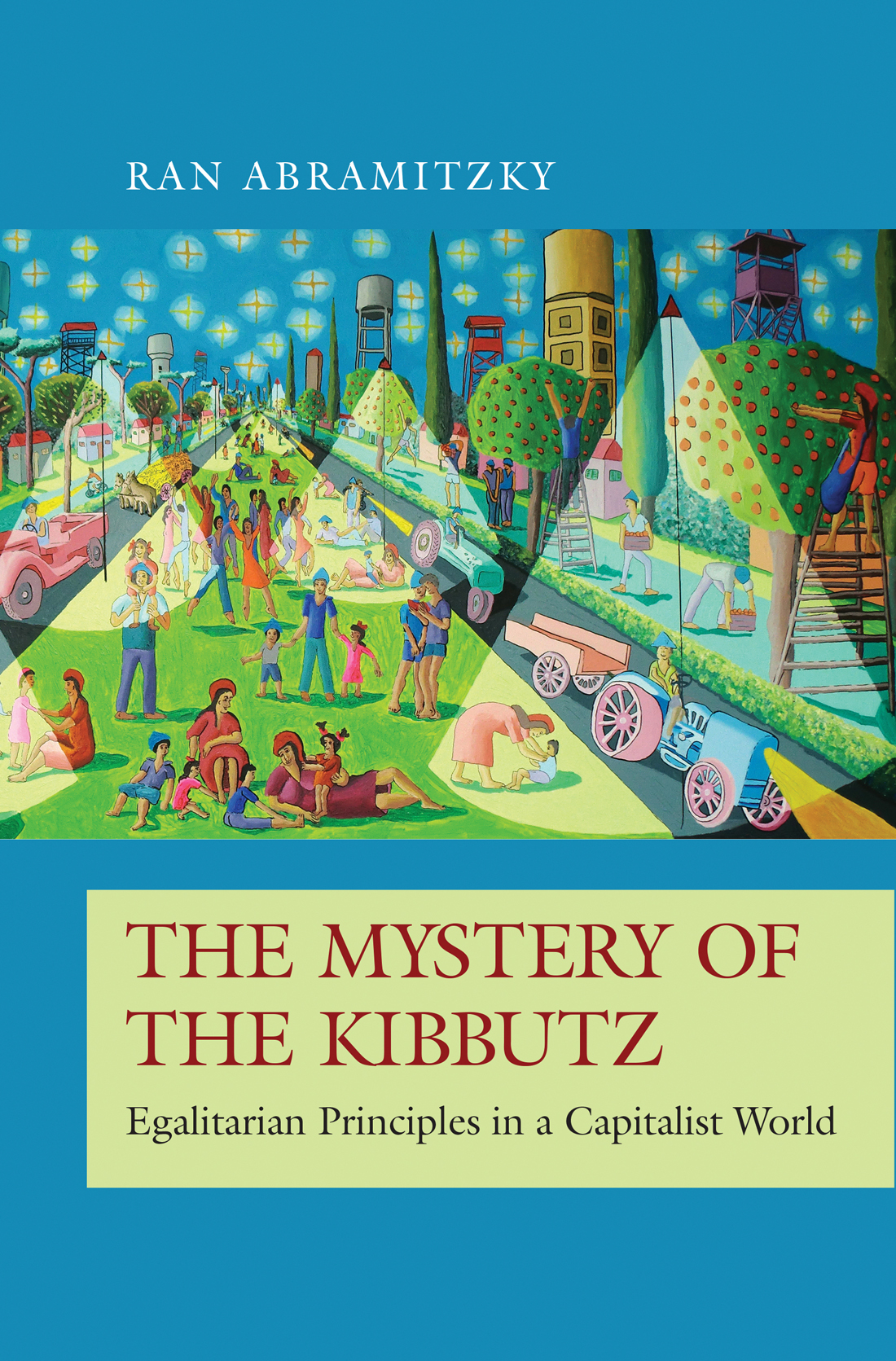

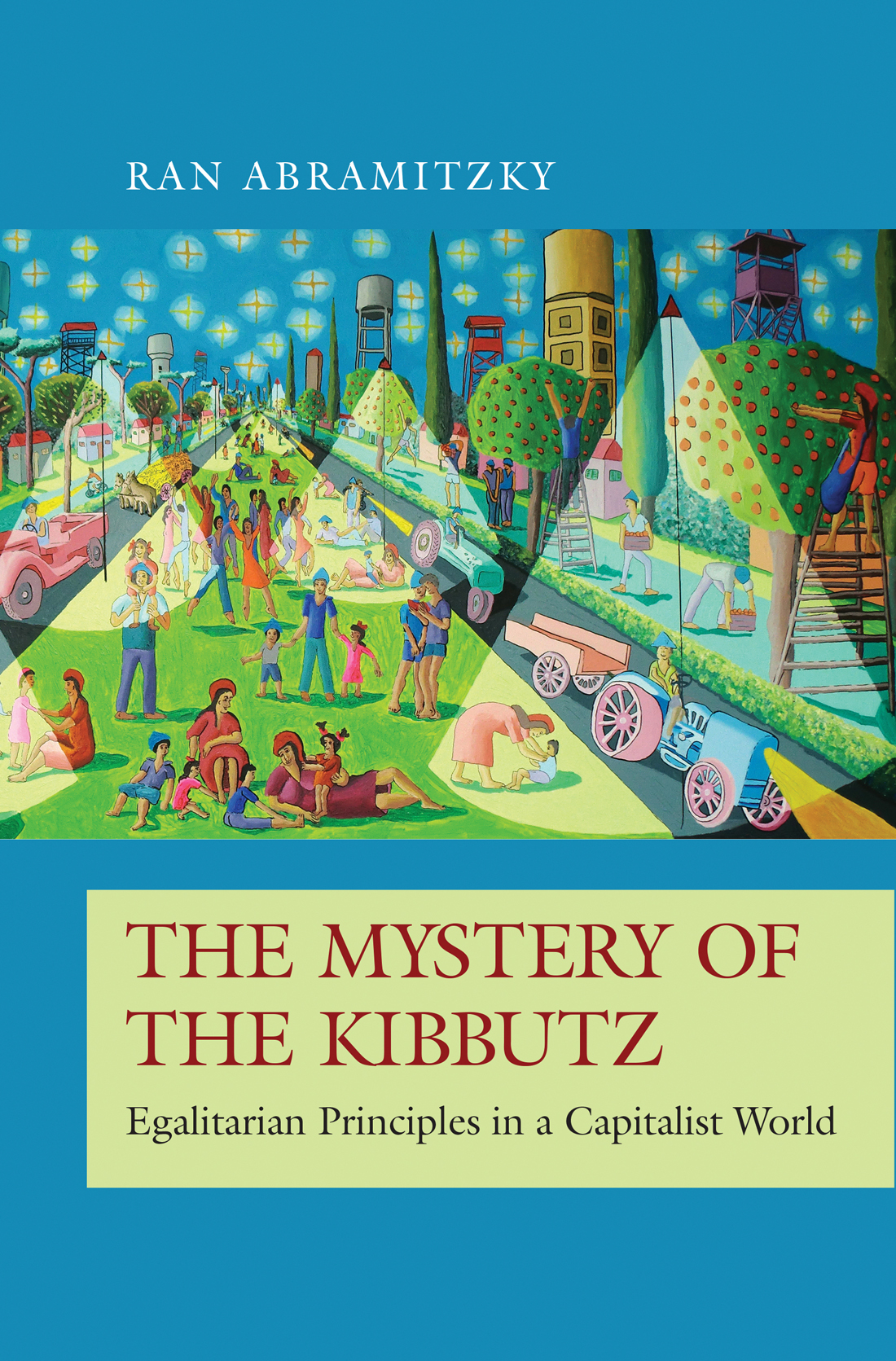

THE MYSTERY OF

THE KIBBUTZ

THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD

J OEL M OKYR , S ERIES E DITOR

THE MYSTERY OF

THE KIBBUTZ

Egalitarian Principles in a Capitalist World

RAN ABRAMITZKY

P RINCETON U NIVERSITY P RESS

P RINCETON AND O XFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

The epigraph on page 75 is with permission from the Estate of Martin Buber, administered by the Balkin Agency. The epigraph on page 181 is from Gary Becker and Richard Posner, The Transformation of the Kibbutz and the Rejection of Socialism. The Becker-Posner Blog, September 2, 2007, with permission from Richard Posner. Epigraphs on pages 269 and 280 by Yacov Oved are reproduced with permission of Stanford University Press.

Jacket image: The Kibbutz, Raphael Perez, in tribute to Yohanan Simon. A traditional kibbutz painted as if it were on Tel Avivs famous Rothschild Boulevard.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780-691-17753-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941908

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in ITC Galliard Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

I NTRODUCTION

The kibbutz puzzle 1

C HAPTER 1

How my grandparents helped create a kibbutz 21

C HAPTER 2

A birds-eye view 39

C HAPTER 3

Why an economist might create a kibbutz 59

C HAPTER 4

On the creation versus survival of societies 79

C HAPTER 5

The free-rider problem 87

C HAPTER 6

The adverse selection and brain drain problems 105

C HAPTER 7

The problem of human capital investment 161

C HAPTER 8

The shift away from equal sharing 181

C HAPTER 9

Why some kibbutzim remained egalitarian and others did not 198

C HAPTER 10

The consequences of rising income inequality 224

C HAPTER 11

On the (lack of) stability of communes: an economic perspective 250

C HAPTER 12

Economic lessons in a nutshell 283

C HAPTER 13

Epilogue 292

THE MYSTERY OF

THE KIBBUTZ

To my wife Noya and our boys,

Roee, Ido, and Tom

INTRODUCTION

The kibbutz puzzle

THE ARGUMENT WITH MY UNCLE

I grew up in Jerusalem, but a central part of my life has always been the kibbutz, a place a few miles from the city and a world away. My grandmother was a founder of Kibbutz Negba in the South of Israel and remained a proud member for fifty-five years; my mother was born and raised in Negba; my aunt and uncle still live in Kibbutz Heftziba in the North; and my brother and his family are members of Kibbutz Ramat HaKovesh near the city of Kfar Saba.

As a child, I admired kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz). My younger brotherin the communal dining hall, filled our plates with as much food and drink as we wanted (Is it really all free, Mom?), and joined other kibbutzniks at one of the long communal dining tables.

As a young teenager, I became even more charmed by kibbutzim. Not only was I having so much fun in Kibbutz Negba (and, less frequently, Kibbutz Heftziba), but the kibbutz principle of completely equal sharing seemed appealing, and the kibbutz way of life idyllic. A community in which everyone was provided for by the kibbutz according to her needs struck me as fair and virtuous.

But as I grew older, I began asking myself questions I couldnt easily answer. Why didnt our beloved family friend A., who always held high positions in the kibbutz and was so smart, talented, and hard-working, earn more than others who werent as talented and didnt work as hard? Why didnt the kibbutz reward his talent and efforts? And why didnt he move with his family to Jerusalem or Tel Aviv, where he surely could earn more money and afford a higher quality of life? Why did A. agree to get paid for his esteemed job the same wage as the member who milked the cows or worked in the kibbutz kitchen?

And why did my Uncle U. work so hard at the irrigation factory, getting home late every night, when he would have earned exactly the same regardless of how hard or how long he worked? No one forced him to work hard; in fact, he had always been proud that there were no bosses at the factory and that everyone held the same rank. He liked his job, but I knew he always wished he could spend more time with his family. Why didnt he, since his earnings would have remained the same?

As I studied hard and stressed over exams, I wondered whether my cousins and friends in the kibbutz had weaker incentives to excel in school; after all, in a classic kibbutz, a high school dropout and a computer engineer with a PhD would earn exactly the same wage. I could not help but think that living in a kibbutz seemed a particularly great deal for lazy people or those lacking talent. What could be better for such people than sharing the incomes of brighter and harder-working people like A. and U.?

In time, I realized that I was not the first to ask such questions: many people became skeptical of the kibbutz economy as they grew

I remember distinctly one particular day in the late 1990s: I was in my twenties and pursuing my undergraduate degree in economics. My whole family was enjoying lunch at my aunt and uncles house in Kibbutz Heftziba. By that time, it was acceptable and common for kibbutzniks to have meals at home when they had guests (and even when they didnt). Heftziba was no longer thriving economically and socially, and the atmosphere in the kibbutz was less upbeat than it had been a few years earlier. Heftziba was deeply in debt to the banks, as were many other kibbutzim at the time. Kibbutz members were discussing reforms to waste fewer resources and increase productivity, including radical ideas such as hiring outside managers to run the kibbutz factories and businesses. We sat on the sunny grass overlooking the kibbutz houses and paths, listening to the crickets chirping in the orange trees and greeting kibbutz members returning from lunch at the communal dining hall.

My uncle described the latest path-breaking innovation his plant had made to improve irrigation systems, and mentioned that the kibbutz plant was among the best in the country. I decided to provoke him. I told him that, according to economic theory, the kibbutz plant shouldnt be that good. In fact it, and the entire kibbutz itself, should not even exist. I pointed out that kibbutz members had strong incentives to shirk on their jobs. After all, why would anyone work hard if all she got was an equal share of the output? I told him the term Id learned for this problem in my economics lectures: the free-rider problem. I also pointed out that the most educated and skilled members have strong incentives to leave the kibbutzthe problem of brain drainso why would they choose to stay in a place that forced them to share their incomes with less skilled members? Surely they could earn higher wages in a nearby city such as Afula or Hadera.

Next page