These things only are impersonal:

insomnia, land mines, and long hours of work.

Everything else is ours or not ours,

divided like the world

inside and outside the skin.

Susan Tichy, Volunteers

Another summer. Another war.

Like tinder in a dry valley, it rarely takes much spark to set Israel and its neighbours alight. In the hot months of 2014, Gaza catches fire again. The world watches it burn. As the violence spikes, I cant avert my eyes from the headlines that call to mind the lines from It Is Dangerous to Read Newspapers, an early poem by Margaret Atwood: Each time I hit a key / on my electric typewriter, / speaking of peaceful trees / another village explodes. Decades later, its not any safer to read blogs or Facebook updates, browse Twitter feeds or YouTube channels. My TV, laptop and smartphone scroll a digital tickertape of bomb strikes and body counts, punctuated by diatribes and denunciations from friends and strangers. Most people, like myself, have no real stake in this Middle East feud other than our own curdled sense of outrage.

We need to have an opinion, though, because the bloody stalemate between the state of Israel and the stateless Palestinian people has become the political litmus test of our age. Who you support says who you arepolitically, personally. In a land claimed by two peoples, only one story can be heard at a time.

In the summer of 2014, the catalyst and the conflict prove especially gruesome. Three Jewish pupils, studying at an Orthodox yeshiva in the occupied West Bank, disappear while hitchhiking. Eighteen days later, Israeli authorities find the boys bodies under a pile of stones. The army sweeps through Palestinian villages in search of the killers, while Israeli politicians blame the military wing of Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement. Right-wing Jewish settlers burn an Arab boy to death. Palestinian militants from Hamas renew a campaign of lobbing crude rockets from the coastal enclave of Gaza deeper into Israeli territory. The Israeli Air Force responds with missile strikes. Airlines divert international flights. Israel musters tanks, artillery and tens of thousands of reserve soldiers for a ground assault. Generals dub the new military operation Protective Edge, which sounds like a high-tech shaving device but is far, far bloodier. Images of shattered schools and apartment blocks in Gaza proliferate across the Internet. Anti-war protests turn violent in Paris and other European cities. When Israeli peaceniks march in Tel Aviv, right-wing thugs shout, Death to leftists! Death to Arabs! Hamas militants emerge from hand-dug tunnels near border kibbutzes and kill several IDF soldiers. Israeli commanders tell residents in Gaza to abandon neighbourhoods targeted as missile caches and Hamas command centres. More than 2,000 Palestinians, many women and children, die in a month-long storm of concrete and shrapnel.

I live thousands of miles away, along the Pacific shoulder of North America, on an island as lush and placid as Gaza and southern Israel are dry and volatile. And yet I am drawn into a debate in which rhetoric flees from all reason. Torrents of angry words and numbing images cascade down my screens. Israel is an apartheid state of baby killers and war criminals! Gaza is ruled by Jew-hating Islamo-fascists who martyr their children as human shields! #GazaUnderAttack and #StandWithIsrael compete for clicks from armchair slacktivists like myself. My sympathies ping-pong between the Israelis I know, threatened by rocket fire and terror tunnels, and the horror show broadcast from the bombed-out, body-strewn streets of Gaza. I dont recognize the Israel where I once lived, the country to which I have returned several times. I cant hear the voices of the people, Jews and Palestinians alike, who spoke to me of hope and reconciliation.

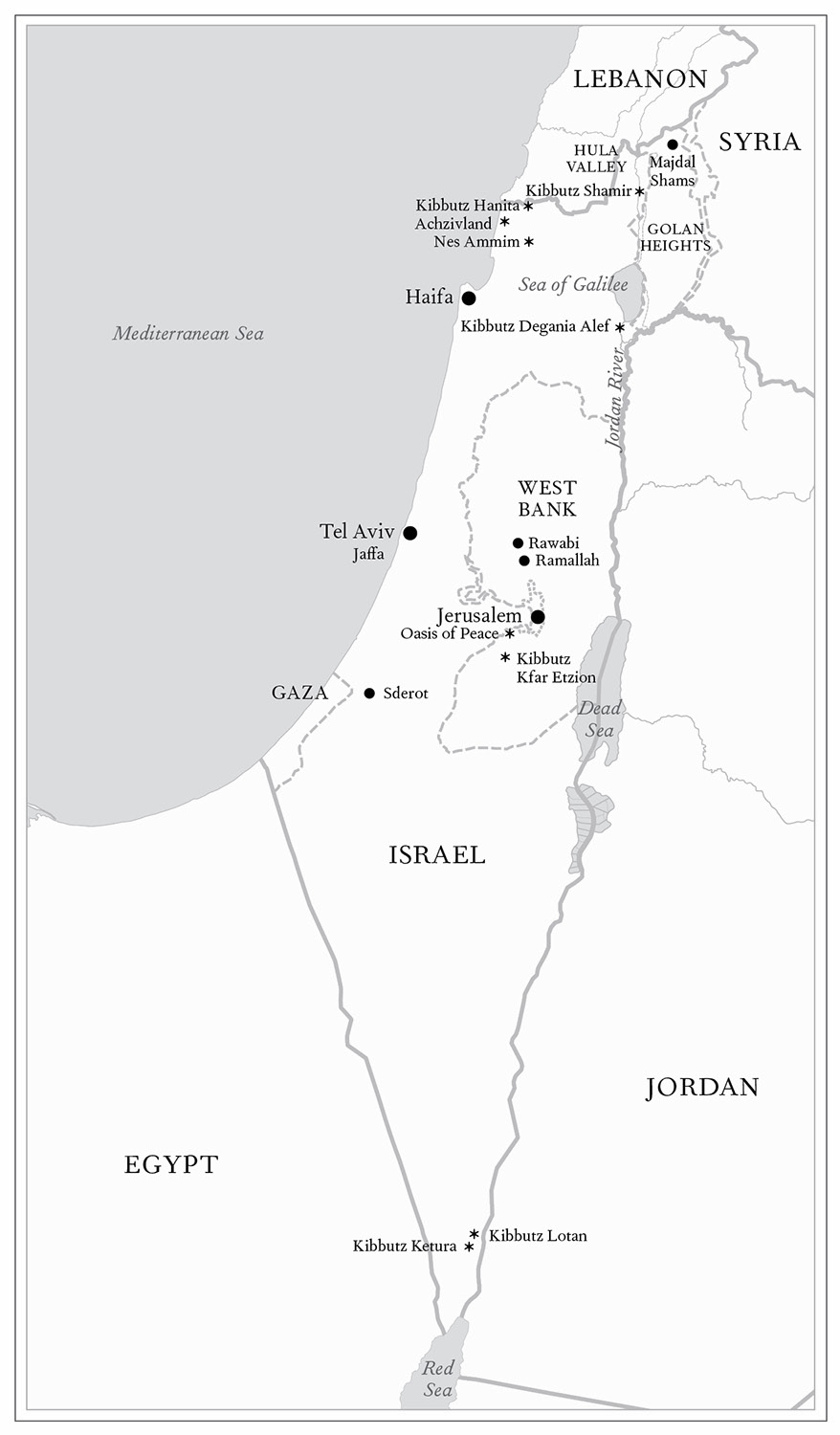

In the weeks after the ceasefire, the Israel Defense Forces and Hamas will pull back to the heavily armed no-mans land of mutual antipathy that divides Israelis and Palestinians. Politicians and pundits will proclaim victory. The Internet will assign blame. Both sides will mourn their dead. And I will be left to wonder, What happened to the original vision of this nation? The Israel I know began more than a hundred years ago with twelve pioneers on the shores of the Jordan River. It began with a naive faith that these young dreamers could break ground and build a peaceable society for the long-exiled Jewish people and share the land of Palestine with their Arab neighbours. It began in the hope that, by living as equals, they could inspire the rest of the world to throw off the shackles of envy and overcome our long-held tribal hatreds. It began with the kibbutz.

Anyone who has never lived on a kibbutz doesnt understand the first thing about it. Its impossible to understand from the outside and this whole investigation of yours is pointless.

Batya Gur, Murder on a Kibbutz: A Communal Case

Every child is born utopian. Our urge to create new worlds kicks in as soon as we can lift a block or wield a crayon. We build towers as precarious as Babel. We design tiny cities, guided by the divine laws of Lego or Fisher-Priceand now Minecraft. We imagine societies with leaders and followers, heroes and villains, histories and intrigues. Our instincts to build worlds and tell stories are entwined, a double helix of human creativity. Overshadowed by an adult society we cant quite understand, let alone control, we build microcosms over which we can rule.

Like most kids, I was obsessed with building worlds. Growing up, I engineered neighbourhoods for legless, bullet-headed toy figurines and played grade-school Jane Jacobs in my parents basement. An old Kodachrome photo reveals a boy in a blond bowl cut, ever the good Catholic, arranging his Star Wars action figures on tiny wooden pews so they can attend Sunday Mass; in my galaxy far, far away, Boba Fett the bounty hunter needed to attend confession. My oddest obsession was the Maginot Line. At 11 or 12, I read about Frances military fortifications in an illustrated history text. Built in the 1930s to withstand a German assault, the Maginot Line became a Second World War footnote when the Nazis did an end run through Belgium on their blitzkrieg to Paris. I didnt care if the Maginot Line worked. To my young eyes, it was a marvel of design, an entire world carved beneath the surface of the earth. I was fascinated by the architecture, the cross-sections of underground chambers, tunnels and armamentsa subterranean network for a strategically inept nation of mole people. I filled notebooks with Maginot renovations and populated my corridors with bustling stick men.

Lewis Mumford, the American social critic and urban historian, called our instinct toward city-making a will-to-utopia. It is our utopias that make the world tolerable to us, he wrote in 1922. The cities and mansions that people dream of are those in which they finally live. In