Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the bereaved families of my young fallen comrades

They say, Whether our lives and our deaths were for peace and a new hope or for nothing we cannot say: it is you who must say this.

They say, We leave you our deaths: give them their meaning

A RCHIBALD M ACLEISH ,

The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak

They say you can read a persons feelings on his face. I f so, I must be a very good actorthe opposite of what anyone who has worked closely with me would tell you. Maybe it was just the exception that proved the rule. But I was described as looking defeated. Distressed. Depressed.

As I delivered my brief final statement outside the presidential retreat at Camp David, in the forested Catoctin Hills north of Washington, DC, I felt none of those things. Yes, I was disappointed. I realized that what had happened over the last fourteen days, or, more crucially, what had not happened, was bound to have serious consequences, both for me personally as prime minister of Israel, and for my country.

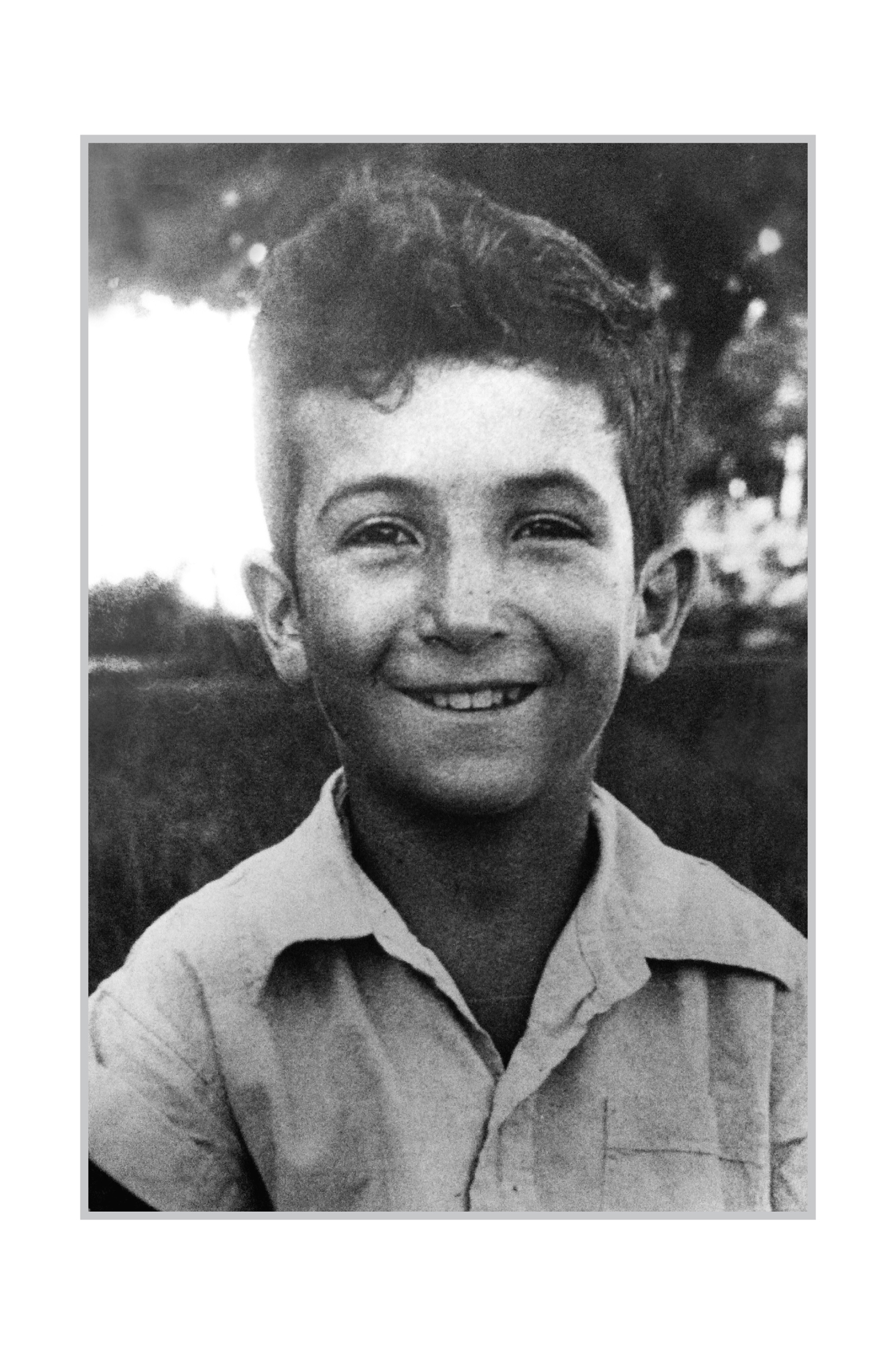

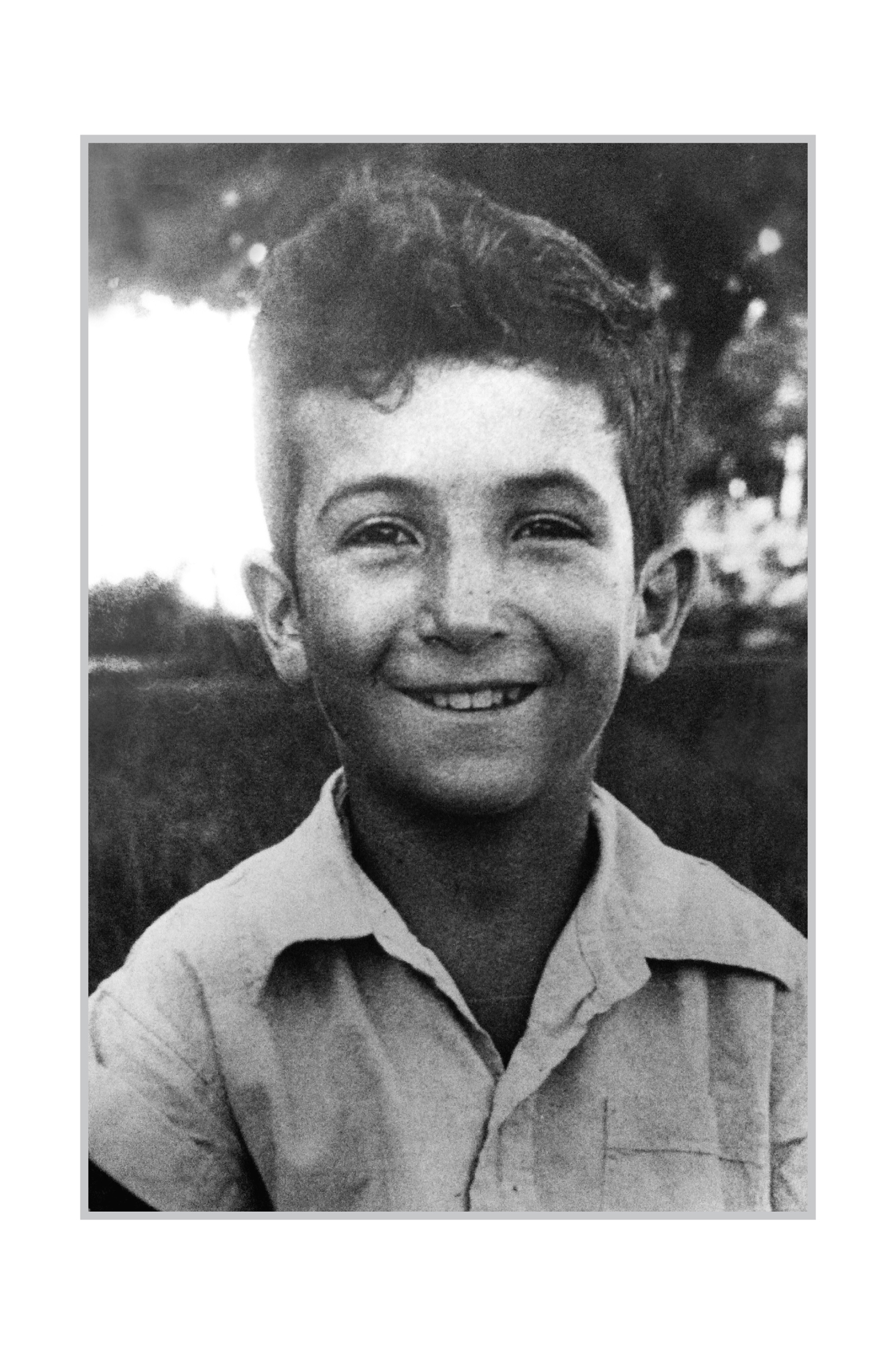

At the time of the Camp David summit in July 2000, however, Id been a politician for all of five years. Most of my life by far had been spent in uniform. As a teenager, small and slight and not even shaving yet, I was part of the founding core of a unit called Sayeret Matkal, Israels equivalent of Americas Delta Force or Britains Special Air Service (SAS). Though as a young kid I was quiet, serious, and contemplative, my years in Israels elite special forces unit, especially when I became its commander, etched those qualities in me more deeply. They also added new ones: a sense that you could never plan a mission too carefully or prepare too assiduously; an understanding that what you thought, and certainly what you said, mattered a lot less than what you did ; and above all, that when one of our commando operations was over, you had to take a step back and evaluate things honestly, without illusions.

That intense focus and detachmentsometimes to the frustration of politicians and diplomats working alongside meguided me from the day I became prime minister. In my first discussions with US president Bill Clinton a year earlier, during a long weekend beginning at the White House and moving on to Camp David, I had mapped out in detail the steps I believed we would have to take in order to address the central issue facing Israel: the search for peace.

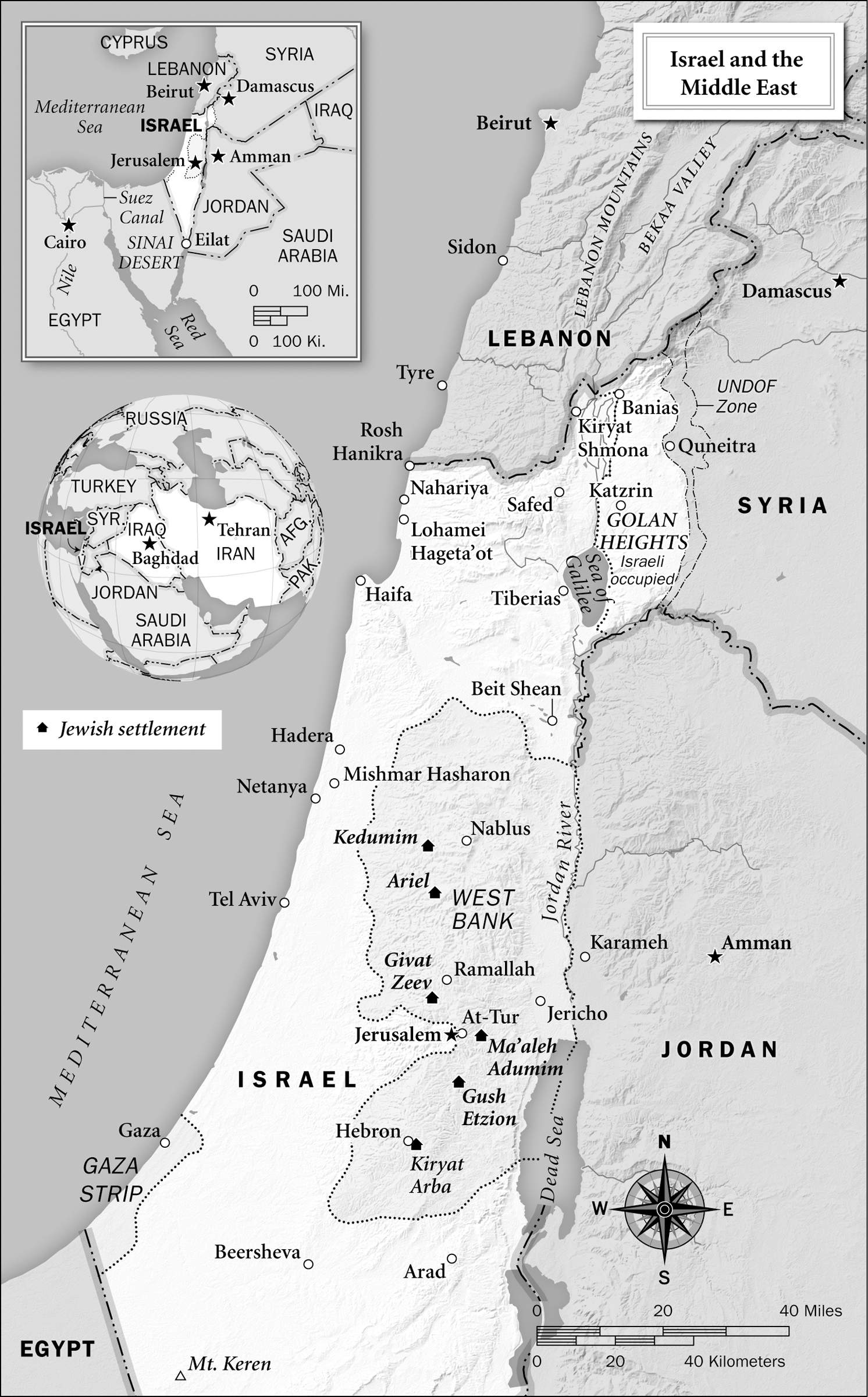

In choosing to return to Camp David for the summit talks with Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat, I was aware of both the stakes and the risks. Success would mean not just one more stutter step away from our century-long conflict: it would be a critical move forward toward a real, final resolutionin treaty-speak, end of conflict . Whatever the complexities of putting an agreement into practice, and no matter how long it might take, we would have crossed a point of no return. After all the suffering and bloodshed on both sides, we would be on the path to two states, for two peoples.

And if we failed? I knew from months of increasingly stark intelligence reports that an explosion of Palestinian violence would be only a matter of time. Indeed, there was every indication the explosion was coming anyway.

I knew something else as well. This was a moment of truth not just for me or for Bill Clinton, who understood our conflict more deeply, and was more determined to help end it, than any other US president. It was a moment of truth for Arafat. The Oslo Accords of 1993 and 1995, groundbreaking though they were, had created a peace process , not peace. Over the past few years, that process had been lurching from crisis to crisis. Political support for negotiations was fraying. Yet the core issues had not been resolved. In fact, theyd barely been touched on. The reason for this was no secret. For both sides, these questions lay at the heart of everything wed been saying for years, to the world and to ourselves, about the roots of the conflict and the minimum terms we could accept. At issue were rival claims on security, borders, settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the future of the ancient city of Jerusalem; none could be resolved without painful and politically difficult decisions.

Entering the summit, I was confident that, along with my team of aides and negotiators, we would do our part to make an agreement possible. I had no doubt that President Clinton, whom I had come to view not just as a diplomatic partner but a friend, would rise to the occasion. But Arafat? There was no way to know. That was why Id pressed Clinton so hard to convene the summit. That was why, despite the misgivings of some of his closest advisers, he had agreed. We both knew that the so-called final-status issues couldnt be put off forever. Untangling them was getting harder, not easier. We also realized that only in an environment like Camp Davida pressure cooker was how Id described it to Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albrightwould we ever discover whether a peace deal could in fact be done.

Now, at least, we knew.

* * *

Our equivalent of Air Force One, perhaps in a nod to our countrys austere early years, was an almost prehistoric Boeing 707. It was waiting on the runway at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington to ferry me and the rest of our team back to Israel.

As we took off, the mood on board was sober. Huddling with the core of my negotiating teampolicy coordinator Gilead Sher, security aide Danny Yatom, and acting foreign minister Shlomo Ben-AmiI could see that the way the summit ended had hit them hard. It was true, as they often reminded me, that I was the one who ultimately had to decide what we could offer in search for a true peace with the Palestinians. I was the one who would be blamed by the inevitable critics, whether for going too far or not far enough, or simply because the deal had eluded us. Yet these three dedicated menGili, by training a lawyer; Shlomo, an academic; and Danny, a former Mossad chief as well as my deputy when I was commander of Sayeret Matkalhad been through dozens of hours of talks with Arafats top negotiators, not to mention their countless other meetings before we got to the summit. Now they had to come to terms with the reality that, even with the lid of the pressure cooker bolted down tight, wed been unable to secure the agreement that each of us knew had been within reach.

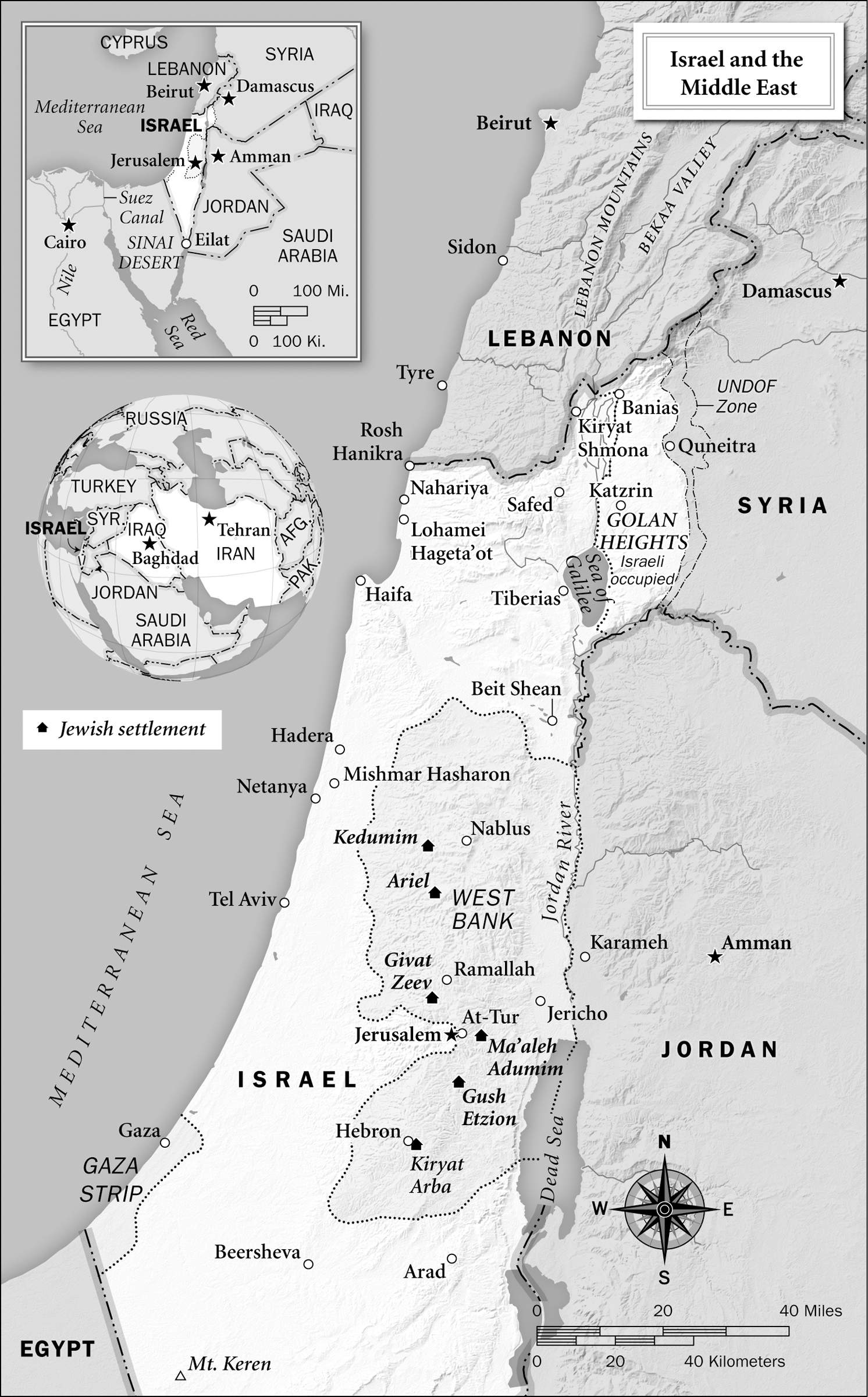

Wed been ready to contemplate major compromises on every one of the key issues as long as we safeguarded Israels vital national and security interests. We had been open to an Israeli pullout from nearly all of the West Bank and Gaza, with a support mechanism to help compensate tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees from the serial Arab-Israeli conflicts of the past half century. Most painfully, and controversially, we had agreed to let President Clinton present an American proposal offering the Palestinians sovereignty over all the Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem as well as custodial sovereignty over the Haram al-Sharif, the mosque complex perched above the Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism. Yet precisely because we had been ready to offer so muchonly for Arafat to reject it all even as a basis for further talks on a final dealI knew how gutted my key negotiators felt.