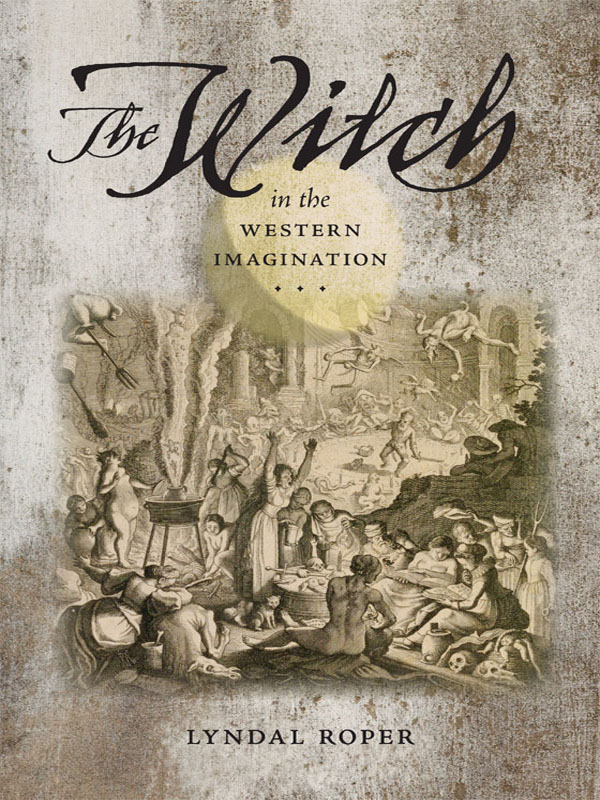

Roper Lyndal - The Witch in the Western Imagination

Here you can read online Roper Lyndal - The Witch in the Western Imagination full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: University of Virginia Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Witch in the Western Imagination

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Virginia Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Witch in the Western Imagination: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Witch in the Western Imagination" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Witch in the Western Imagination — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Witch in the Western Imagination" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE WITCH IN THE WESTERN IMAGINATION

RICHARD LECTURES FOR 1998

A volume in the series

Studies in Early Modern German History

University of Virginia Press

2012 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2012

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roper, Lyndal.

The witch in the Western imagination / Lyndal Roper.

p. cm. (Richard lectures for 1998)

(Studies in early modern German history)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-3297-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8139-3300-9 (e-book)

1. Witches in art. 2. Witches in literature. 3. Arts, European Themes, motives. 4. Arts and society Europe. I. Title.

NX652.W58R67 2012

700'.477dc23 2011045233

For Charles Zika,

WHO SHOWED ME

HOW TO LOOK

Contents

Acknowledgments

THIS COLLECTION of articles grew out of my teaching at the University of Oxford, and I would like to thank all the students who commented on the witchcraft cases I discuss here, and who showed me just how interesting the images were. I would also like to thank Robin Briggs, with whom I taught many graduate classes on methodology and on witchcraft where some of these ideas were tried out. was written to honor my good friend, the late Trish Crawford, whose work in feminist history inspired so many of us.

The University of Oxford and Balliol College Oxford gave me sabbatical leave, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation gave me a term in Berlin, Germany, during which I was able to complete several of these essays. Gisela Bock and Claudia Ulbrich of the Free University Berlin welcomed me and offered me room in the History Faculty. The Max Planck Institut fr Geschichte in Gttingen was an intellectual home for over a decade, and I met many scholars there. The Fell Fund of the University of Oxford enabled me to gain the help of Alan Ross, whose sharp eyes assisted in editing the chapters and removing repetitions. Susan Murray was a wonderful copy editor and correspondent; Raennah Mitchell dealt with endless very complex queries; Mark Mones was a model of efficiency; Margie Towery supplied a superb index; and Dick Holway was a helpful and very supportive editor and a most patient one, too.

for Alf Ldtke, friends who, over the years, have inspired and influenced me. Many other individuals have helped me, too, and I would like especially to thank Jim Amelang, Ingrid Btori, Rainer Beck, Wolfgang Behringer, Willem de Blcourt, Ruth Bottigheimer, Max Brewer, Laurence Brockliss, Peter Burke, Stuart Clark, Natalie Zemon Davis, Jonathan Durrant, tienne Franois, Laura Gowing, Klaus Graf, Valentin Groebner, Rebekka Habermas, the late Olivia Harris, Bridget Heal, Jan Hennings, Kat Hill, Clive Holmes, Michael Hunter, John Jordan, Roland Kufner, Hans-Jrg Knast, Natalie Kwan, Simone Laqua, David Lederer, Alison Light, Suzie Lipscomb, Jan Machielsen, Rebekka von Mallinckrodt, Hans Medick, Erik Midel-fort, Lucia Nixon, Caroline Oates, David Parrott, the late Alison Patrick, Iain Pears, Daniel Pick, Helmut Puff, Thomas Robisheaux, Ailsa Roper, Cath Roper, Stan Roper, Ulinka Rublack, Tom Safley, Pamela Selwyn, Jim Sharpe, Alex Shepard, Pat Simons, Jenny Spinks, Janice Stargardt, Giora Sternberg, Kathy Stuart, Maria Tausiet, Barbara Taylor, Ann Tlusty, Selina Todd, Alex Walsham, Roisin Watson, Bernd Weisbrod, Tim Wilson, and Amy Wygant, for stimulating conversations and ideas that have found their way into this book. The staff at many institutions assisted me, in particular, Dr. Georg Feuerer and the Stadtarchiv Augsburg, Dr. Christoph Nicht and the Stdtische Kunstsammlungen Augsburg, the Bodleian Library Oxford, the British Library, especially Auste Mickunaite, Glasgow University Library and its Special Collections, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Staatsbibliothek Berlin, the Straubingen Stadtarchiv, Dr. Martin Kaulbach of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, the staff of the Stadtmuseum Nrdlingen, and the staff of the Fembohaus Nuremberg. In Nuremberg, Dr. Roland Kufner kindly took photographs for me, and Dr. Thomas Eser of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum was helpful way beyond the call of duty.

I owe a huge debt to Erik Midelfort, who first invited me to give the Richard Lectures at the University of Virginia. This book, I fear, bears almost no relation whatsoever to the lectures I gave over a decade ago now; but it was his idea that produced the book. Erik has done more than anyone to shape scholarship on witch-hunting in Germany, and we all profit from his generosity and boundless energy. Stuart Clarks brilliant rethinking of the history of witchcraft has influenced my own work profoundly, as has Robin Briggss deep understanding of the dynamics of witchcraft in Lorraine. I am not an art historian, and there is much I had to learn: I would like to thank Johannes Wilhelm, who first introduced me to Augsburgs monuments and to so many churches; Pat Simons, to whose work on gender and images I owe so much; the artist Miranda Cresswell, who looked at handwriting and paintings with me; and Bernhard Jussen, whose example suggested ways historians and artists might work together. Conversations with Alison Light over the years have shaped many of these essays, and my brother, Mike Roper, has been a truly supportive reader who has got me out of many a writing fix. Ruth Harris read every chapter. Her powerful intelligence and intuitive grasp of arguments I often could not formulate have made this book much better than it would otherwise have been my debt to her is immense. Nick Stargardt is my fiercest and most insightful critic and alas, always right. All the chapters owe more than I can say to him, for I am no longer sure which ideas were his and which mine. Our sons, Anand and Sam, have reminded me of all the most important things in life, even if I could not always persuade them to come inside yet another church. Finally I would like to thank Charles Zika, to whom this book is dedicated, and the Department of History at Melbourne, where I was an undergraduate, and which is a remarkable community of scholars. Charless inspirational teaching is the reason why I became a historian of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Germany. No scholar can work on images of witchcraft without drawing hugely on his pioneering scholarship.

THE FOLLOWING have been published before, and I am grateful to the publishers for permission to reprint: , The Suicidal Student, in Alltag, Erfahrung, Eigensinn: Historish-anthropologische Erkundungen; Festschrift for Alf Luedtke, ed. Belinda Davis, Thomas Linden-berger, and Michael Wildt (Frankfurt: Campus, 2008).

THE WITCH IN THE WESTERN IMAGINATION

Introduction

T HIS COLLECTION of essays examines one particular cultural theme which had special importance in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that of the figure of the witch. I began assembling it shortly after I had written a book on the witch craze in southern Germany between 1560 and 1800, based on hundreds of trial records from some of the areas of most intense witch-hunting. The book argues that the European witch hunt was fired by an obsession with the power of old women to destroy fertility in the human and the natural world, and it includes a great many pictures. It explores how episodes like these reveal the power of unconscious forces in particular historical epochs, driving hatreds and anxieties of a peculiarly intense kind. The European witch hunt claimed the lives of perhaps as many as fifty thousand to one hundred thousand individuals we will never know the exact total. In mass panics like some of those I investigated, more than a thousand people met their deaths in the space of a generation; and even where witch-hunting remained comparatively restrained, there might be one or two cases which led to trials of extraordinary viciousness against apparently harmless individuals, old women, or even children.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Witch in the Western Imagination»

Look at similar books to The Witch in the Western Imagination. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Witch in the Western Imagination and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.