A M I RIGHT in assuming that you want to buy an elephant? the voice from New Delhi shouted down the telephone to me in London. Even through the hiss and static of the long-distance connection I could detect the apprehension in the voice.

Yes, I shouted back.

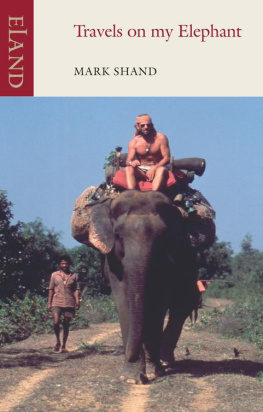

I was restless again. The last time I had been restless, I ended up being pursued by cannibals in Indonesia. This time, I had decided on a quiet jaunt across India on an elephant. This idea evolved from a drawing I had discovered while clearing out my grandmothers house after she had died. The drawing was of an infuriated male elephant about to charge a little Indian mahout or elephant driver. I took it with me and forgot about it at least I thought I had.

A few days later I opened a book on India. Staring jovially at me from the page was a bewhiskered gentleman, wearing a dashing plumed hat, sitting nonchalantly astride an elephant. It was Tom Coryat, the eccentric Englishman who travelled to India overland in 1615, on foot, on twopence a day. When he reached the court of the great Moghul Emperor Jahangir, he wrote: I have rid upon an elephant since I came to this court, determining one day (by Gods leave) to have my picture expressed in my next booke sitting upon an elephant. I was now obsessed. With or without Gods leave I was determined to have my picture expressed in my next book sitting upon an elephant.

I rushed to the library where I read a few classics on elephants. From the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, I received sound information:

The great elephant has by nature qualities which rarely occur among men, namely probity, prudence and a sense of justice. They are mild in disposition and are conscious of dangers. If one of them should come upon a man alone who has lost his way, he puts him back peacefully in the path from which he has wandered. It is so peaceable that its nature does not allow it willingly to injure creatures less powerful than itself. If it should chance to meet a drove or flock of sheep, it puts them aside with its trunk so as to avoid trampling upon them with its feet; and it never injures others unless it is provoked. They have a great dread of the grunting of pigs and they delight in rivers. They hate rats. Flies are much attracted by their smell and as they settle on their backs they wrinkle up their skin deepening its tight folds and so kill them.

How could I go wrong? It seemed I had chosen a most practical and agreeable travelling companion.

Now I was telephoning a friend in New Delhi. Yes, I want to buy an elephant, I shouted to him, as if this was the most usual of requests.

You must be mad, his voice echoed. Still, I suppose its possible. India is full of elephants, but what are you going to do with it when you leave? I dont see your parents taking kindly to it residing in Sussex. Think of their beautiful garden. Why dont you rent an elephant?

Rent one? I yelled. Its not a car.

All right, Ill see what I can do. I could hear the resignation in his voice. Meanwhile I suggest you contact Pepita. I think she has an elephant.

Thank you so much. Goodbye.

Mark, he shouted frantically. Theres just one other thing. Where are you going to go on it?

Well, um er I stuttered feebly. To be frank, I havent really given it much thought yet. In fact, I had not thought about it at all. I just imagined myself climbing aboard and setting off.

Pepita Seth is an unconventional English woman, married to one of Indias finest actors. A scholar and talented photographer, she spent ten years in Kerala documenting the religious rituals of southern India. There she became obsessed with the elephant that so enriches Keralas ceremonies and festivals. Now she lives in Delhi. I wrote asking if I could buy her elephant. Pepita replied promptly. Her writing paper ELEPHANT OWNERS ASSOCIATION announced what surely must be the most exclusive club in the world: No, I could not buy her elephant, she wrote indignantly. On the other hand I know where you can get one. The Sonepur Mela in Bihar, the worlds largest animal fair. Elephants, cattle and horses have been sold there for centuries. I went three years ago and must have seen three hundred elephants. It happens sometime at the end of November, depending on the full moon.

It was now the beginning of August and the Mela was not for another four months. I couldnt wait that long. I decided to leave for India immediately certain that I would find an elephant once I got there. After all, I now had a goal a place to sell it. I just had to find one and ride to the fair.

I NDIA SHOWS WHAT she wants to show, as if her secrets are guarded by a wall of infinite height. You try to climb the wall you fall; you fetch a ladder it is too short; but if you are patient a brick will loosen and then another. Once through, India embraces you, but that was something I had yet to learn.

When I arrived in Delhi it was my ladder that was too short. I wanted everything immediately. The monsoons had broken. Black, swollen clouds brought the usual rain, humidity and chaos. Roads were awash, taxis broke down, peacocks screamed. I perspired, worried and developed prickly heat and I had only been there a few days.

Inevitably I consulted a fortune-teller. You are married, yes, he stated wisely.

No, I replied.

But you are having a companion, I think.

Yes.

You are most fortunate, sir. Soon you will be having another one. I am seeing many problems. But do not worry, sir, he added brightly. They will only be getting worse.

With characteristic generosity my friend had put his house at my disposal. It was to become elephant headquarters and the mantle of co-ordinator had settled, however unwillingly, upon his shoulders. In the following week his elegant dining-room was converted into an operations area fit for a world war. Maps and papers littered the table, kit bags, medical supplies, mosquito nets, tents and food rations occupied corners. People dropped in and out. The telephone never stopped ringing and his staff worked overtime producing a continuous chain of refreshments. Game wardens, wildlife officials and forest officers, retired shikaris, politicians, journalists, government servants, ministers and just plain friends were contacted all important people with tight schedules who went out of their way to help. Undeservedly, however, the bricks had already been loosened for me.

Everybodys so kind, I remarked to my friend incredulously.

It is not you that theyre worried about, its the elephant.

In this merry-go-round of madness I sloshed from office to office pestering people. I spent a morning discussing the reproduction cycles of the gharial, the Indian freshwater crocodile, and another looking at slides of seabirds. I was offered a camel and found myself buying a jade green parrot from a mobile bird seller, which promptly bit me. I listened carefully to mercurial advice on ancient routes and less carefully to lectures about pilgrimages and migrations affected by lunar and solar cycles. I heard about the great temples and festivals I would see, the jungles I would travel through and the tribals that I would encounter. And elephants? I would eventually enquire hopefully.

India is like an elephant, I was told. She moves slowly.

At last a vital brick fell out. Through my friend I met an important bureaucrat who had a deep knowledge of wildlife and, more important, was an expert on elephants.

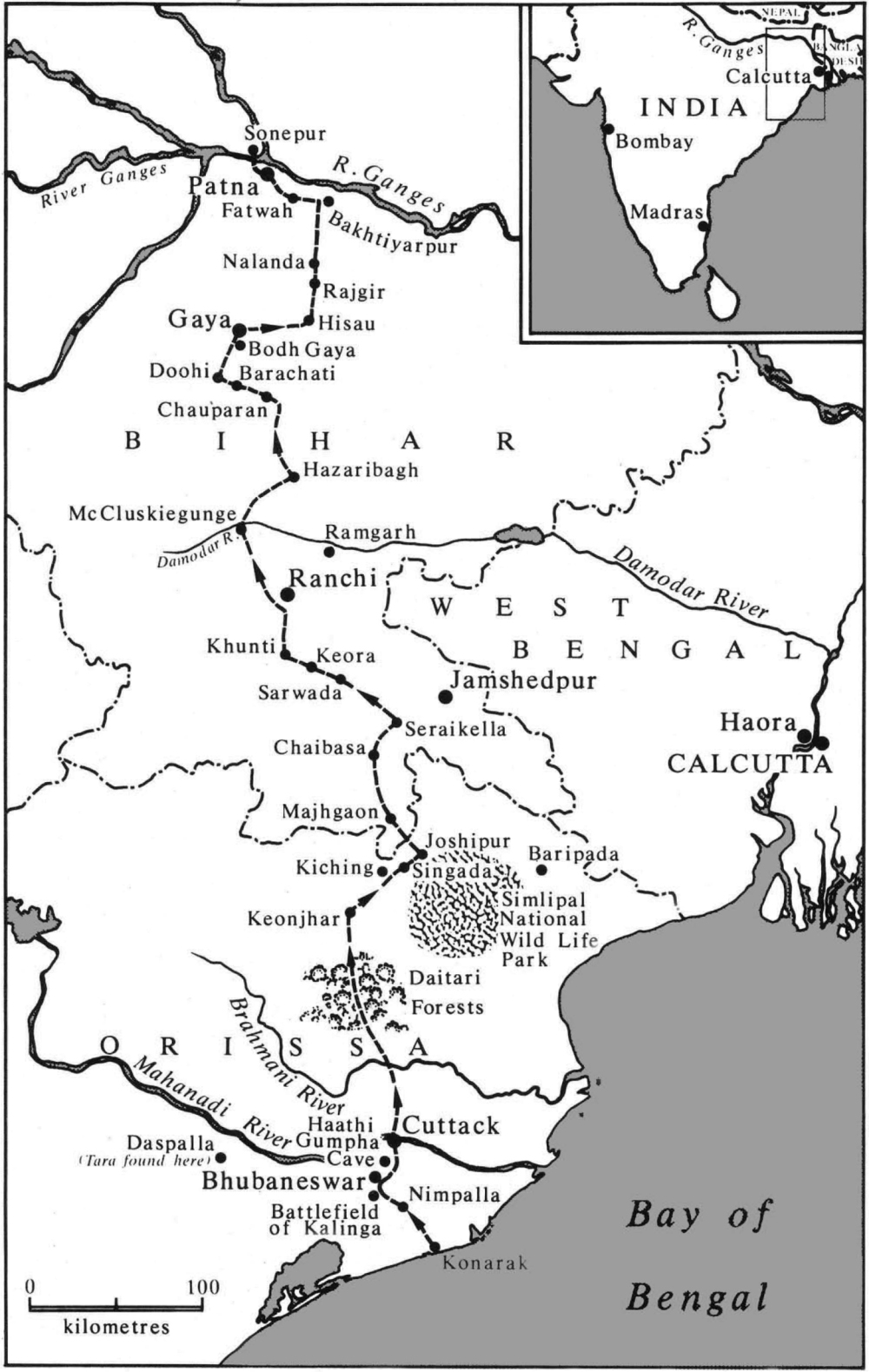

Orissa, the old kingdom of Kalinga, he said, studying the map I had spread before him, is where you should go. For centuries the rulers paid their tributes in elephants. They were known as Gajpati, the Lords of Elephants. In fact, he continued, you will almost certainly be retracing some ancient elephant route. You tell me that you are ending the journey at the Sonepur Mela in Bihar.