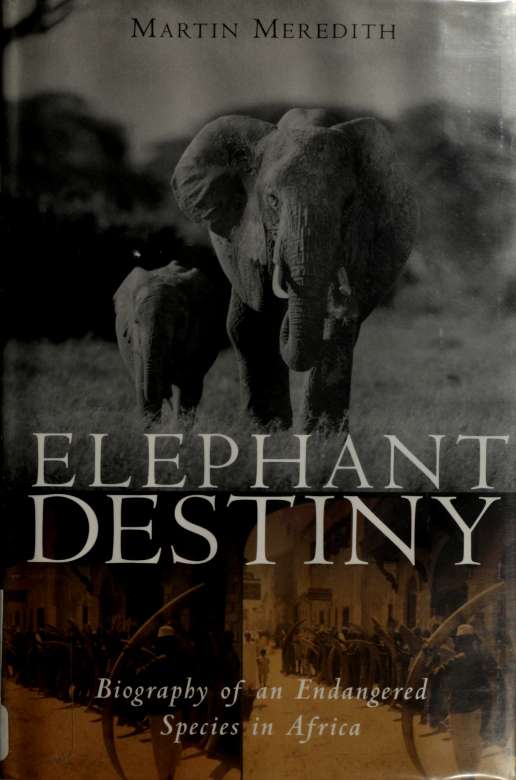

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

I

Jk For Tilly, Daisy, Ellie and Susie

Acknowledgements

The broad nature of this book has meant that I have rehed on the work of many other authors. Starting with Aristotle, the father of elephant science, in the fourth century bc, the trail leads through a landscape of Roman historians, medieval naturalists, Victorian poets, colonial hunters and game wardens, culminating in the endeavours of modern biologists. In recent times, the discoveries of field scientists such as John Perry, Irven Buss, Richard Laws, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, Cynthia Moss, Joyce Poole and Katy Payne have transformed our understanding of the elephant world. I am especially indebted to Iain and Oria Douglas-Hamilton for their generous hospitality and for many memorable days spent at Sirocco on Lake Naivasha, at their elephant archive in Nairobi and at the Samburu Elephant Research Project. I am also grateful to Cynthia Moss, Joyce Poole and staff at the Amboseli Elephant Research Project. My own encounters with elephants have taken place in many different parts of Africa over the years: in the Zambezi Valley, Hwange, Chobe, the Skeleton Coast, the Luangwa Valley, Manyara, Tsavo and the Masai Mara. But nothing has surpassed the enjoyment of watching elephants close up in Samburu and in Amboseli in the company of researchers knowledgeable about their family history and habits. My thanks are also due to Dave Cumming, Karen McComb, Steve Cobb, Juliet Brightmore, Felicity Bryan, Rachel Whitehead, and Peter Osnos and the staff of PublicAffairs.

Manyara

At the foot of a waterfall that cascades down the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley into the Ndala River, there is a pool with sandy edges where elephants like to congregate. Overlooking the pool stands a high bank with views stretching across canopies of flat-topped acacia trees towards Lake Manyara a few miles beyond. It was here, in 1966, that a young Scottish biologist, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, decided to set up camp for what was to become a pioneering study of African elephants.

Douglas-Hamilton's initial assignment was to assess the damage to trees caused by elephants in Manyara, a small national park in northern Tanzania lying between the Rift Valley escarpment and the lake. It contained one of the highest densities of elephant population ever recorded: nearly 500 elephants were estimated to be living in an area of no more than thirty-five square miles. They had recently started to strip bark from acacia thorn trees, destroying whole tracts of woodland. No one knew what they needed from the bark nor what the consequences of the damage they inflicted on the acacia forest would be. The park authorities also wanted to learn more about an elephant migration that occurred in the dry season when large numbers disappeared into a huge cloud forest on top of the escarpment.

Soon after his arrival, Douglas-Hamilton realised the

Elephant Destiny

need for a more thorough, long-term approach to understanding the impact of elephants on their environment in Manyara. Only by ascertaining their birth rates and death rates and their movements in and out of the park w^ould he be able to gain a clear perspective on the scale of the problem. This in turn meant that he w^ould have to acquire the ability to recognise by sight a large number of individual elephants. No one had hitherto undertaken a study of individual elephants in the wild.

Day after day he followed elephants, taking photographs for identification, sometimes on foot, or crouching in trees, or from a battered Land-Rover. The most effective method of identification, he discovered, was to memorise the shape of their ears which were usually marked by notches, slits or holes. Another distinguishing feature was the pattern of veins on their ears which provided as accurate a means of identification as human fingerprints.

The work was hazardous. Each elephant had to be photographed with its ears spread out, facing the camera, a position most commonly adopted when an elephant was alarmed and about to charge. Douglas-Hamilton was charged on countless occasions, making many narrow escapes. Once, following an elephant trail up the escarpment, he was trampled by a rhinoceros and seriously injured.

But gradually the elephants grew accustomed to his presence, accepting him as harmless, and Douglas-Hamilton was able to observe elephant life at close hand undisturbed for hour after hour. He became familiar with their different personalities, naming many of them after friends or literary and historical figures, instead of by scientific numbers.

His cast of characters included: Boadicea, a leading

i

Manyara

matriarch who made fierce threat charges but never carried them through; the ferocious Torone sisters who charged without warning and in total silence; and Virgo, a gentle elephant, intensely curious, who would walk up to Douglas-Hamilton, standing only a few feet away, eventually allowing him to touch the lip of her extended trunk. After four years in Manyara, Douglas-Hamilton had named or numbered almost all the elephants in the park.

By observing them so closely, he gained new insights into their remarkable social life, finding many resemblances to human behaviour. The basis of elephant society, he concluded, was the family unit, led by a matriarch and consisting of sisters and cousins, with their various offspring. Family members were bound by strong ties of loyalty which lasted for life. Cows were devoted to the well-being and protection of their offspring, exercising parental care well into their early teenage years. In times of distress and danger they held fast to their family ties and swiftly combined to ward off threats by predators. Family units in turn were linked to wider 'kinship' groups, usually related, whose company they often shared. In all, Douglas-Hamilton discovered some forty-eight cow-calf family units in Manyara, most of them belonging to larger kinship groups.

To help him keep track of elephant movements, he devised a method of fixing radio collars carrying a transmitter around the neck of an elephant that had been temporarily immobilised by drugs. The first experiments were successful. For twenty days and nights he was able to stay on the trail of a young bull as he wandered up the escarpment, along densely forested gorges and down to the lakeside, recording his eating and drinking habits and the company he kept. As a next step, Douglas-Hamilton

Elephant Destiny

acquired a light aircraft, enabling him to pick up radio signals in the air from a distance as far as thirty miles away, providing far greater scope to plot elephant movements.