Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

To my beautiful, caring Franoise, for allowing me to be who I am.

BOMA a traditional holding pen or enclosure, or a stockade

EMOA Elephant Managers and Owners Association

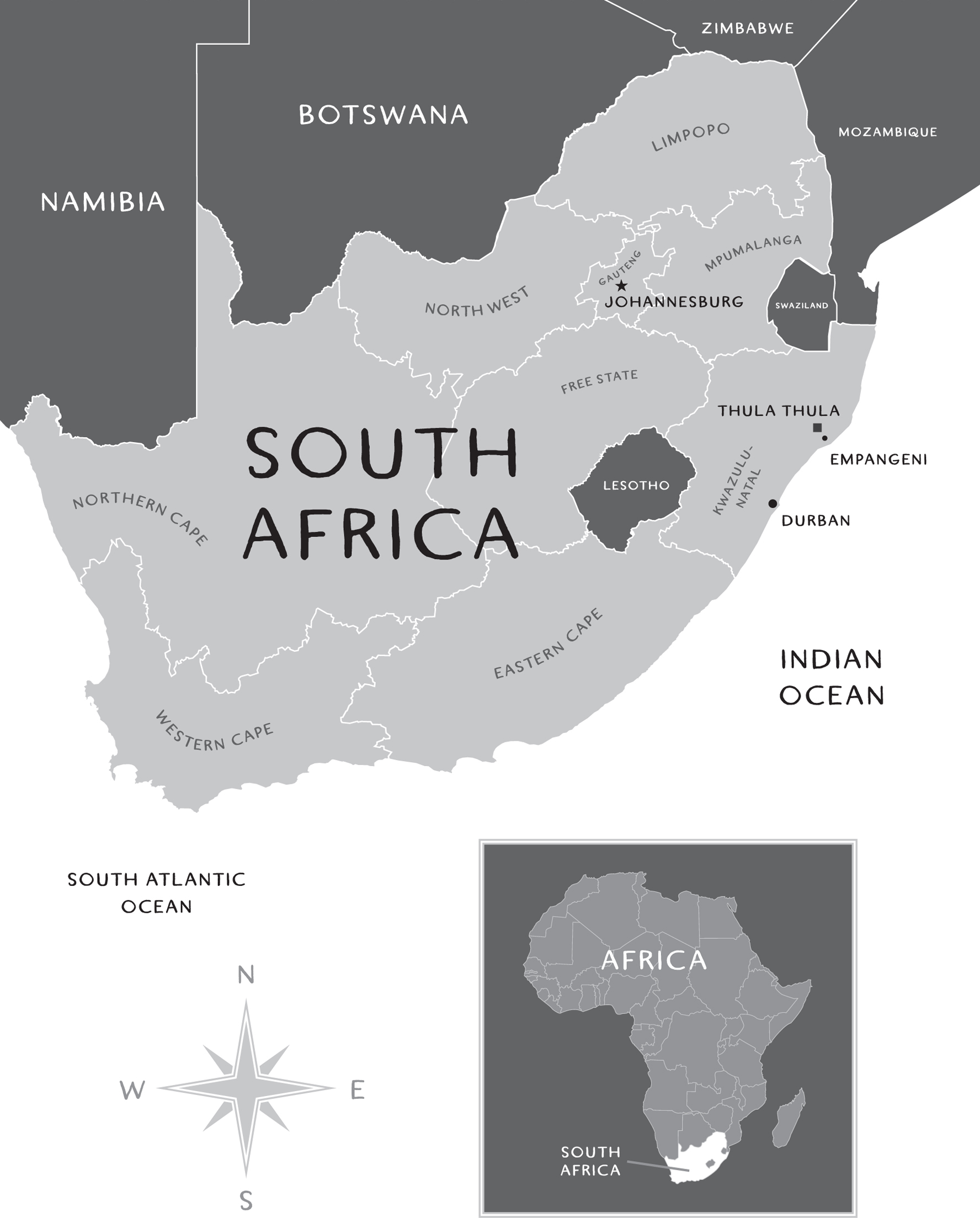

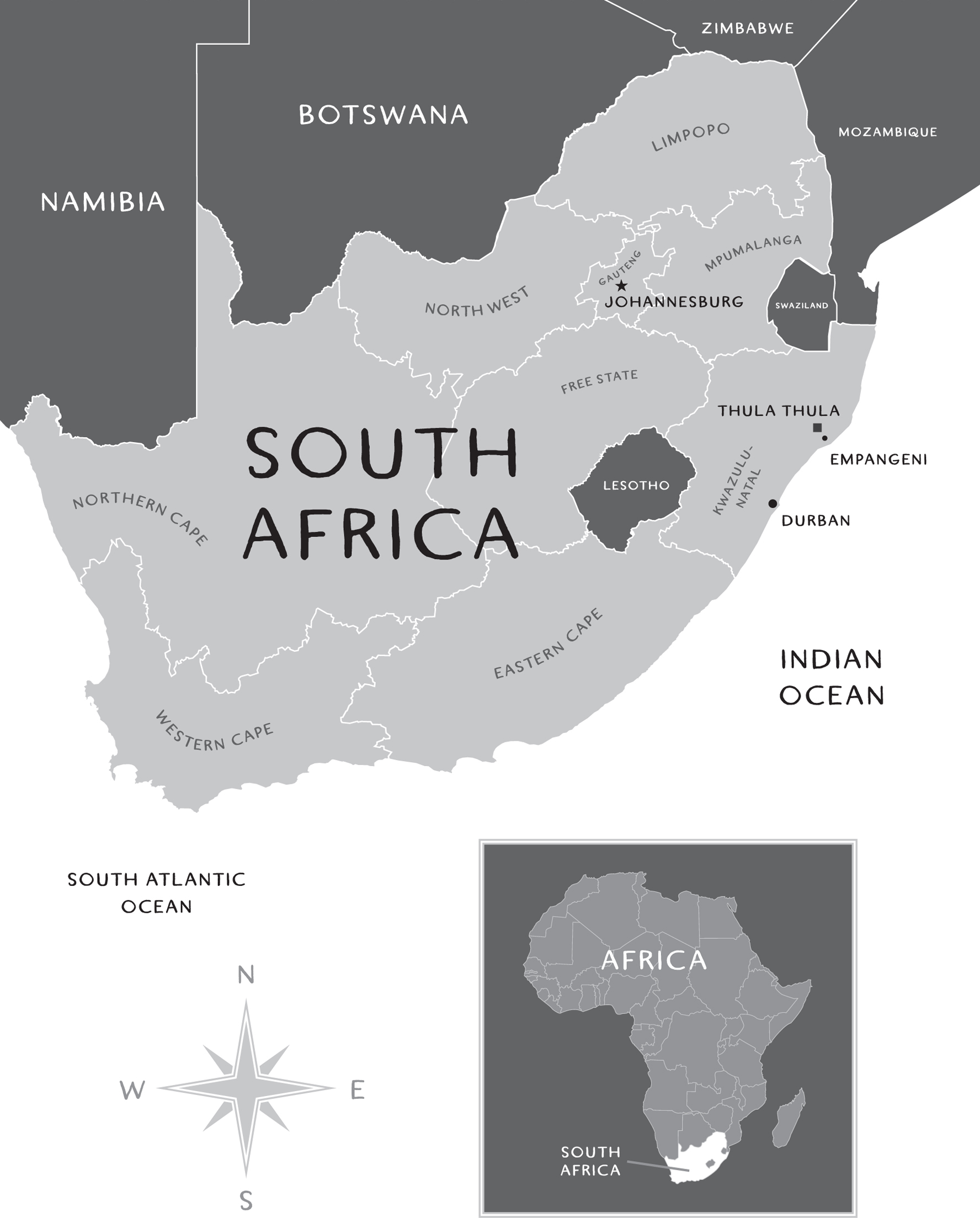

KWAZULU-NATAL the province in South Africa where Thula Thula is located

OVAMBO an ethnic group in South Africa; the largest ethnic group of Namibia

SPOOR tracks, usually of an animal, or any sign or trace to follow

ZULU TERMS

AMAGWERAGWER foreigners

BABBAS a slang term for babies; Lawrence Anthonys term of endearment for his elephants

HAMBA GAHLE go well

HAU an exclamation of surprise

ILANGA the sun

INDUNA (PLURAL: IZINDUNA) headman or foreman of a workforce or group

INKHOSI (PLURAL: AMAKHOSI) overall chief of an ethnic group or clan

MBOMVU emergency call, equivalent to Mayday! or Code Red

MKHULU grandfather; nickname for Lawrence Anthony by his staff

MNUMZANE sir

MVULA rain

NKOSI title of top-ranking chief

SALE GAHLE stay well

SAWUBONA a greeting, literally I see you

YEBO yes

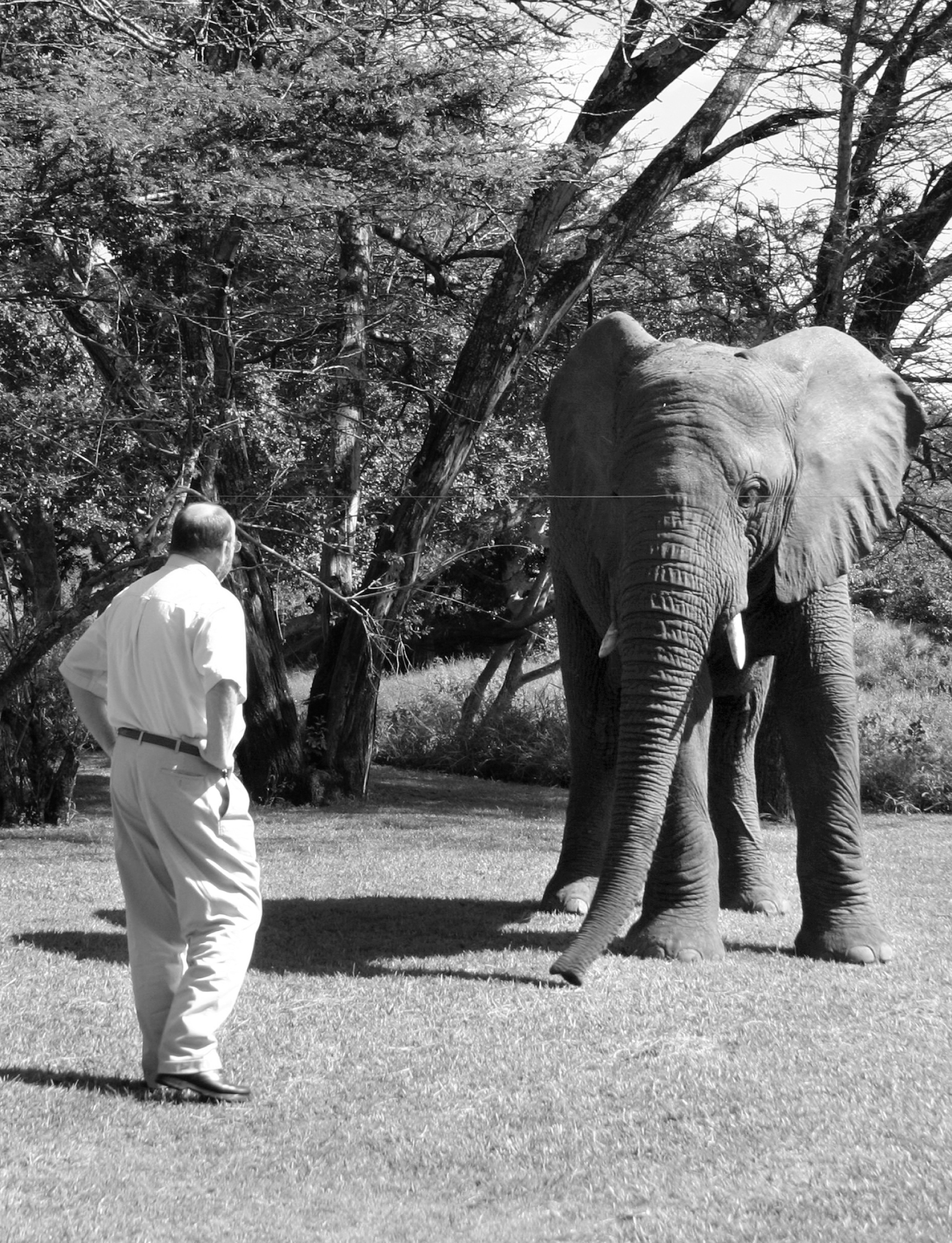

In 1999, I was asked to accept a herd of troubled wild elephants on my game reserve, Thula Thula. I had no idea how challenging it would be or how much my life would be enriched.

The adventure has been both physical and spiritual: Physical in the sense that it was action from the word go . Spiritual because these giants took me deep into their world.

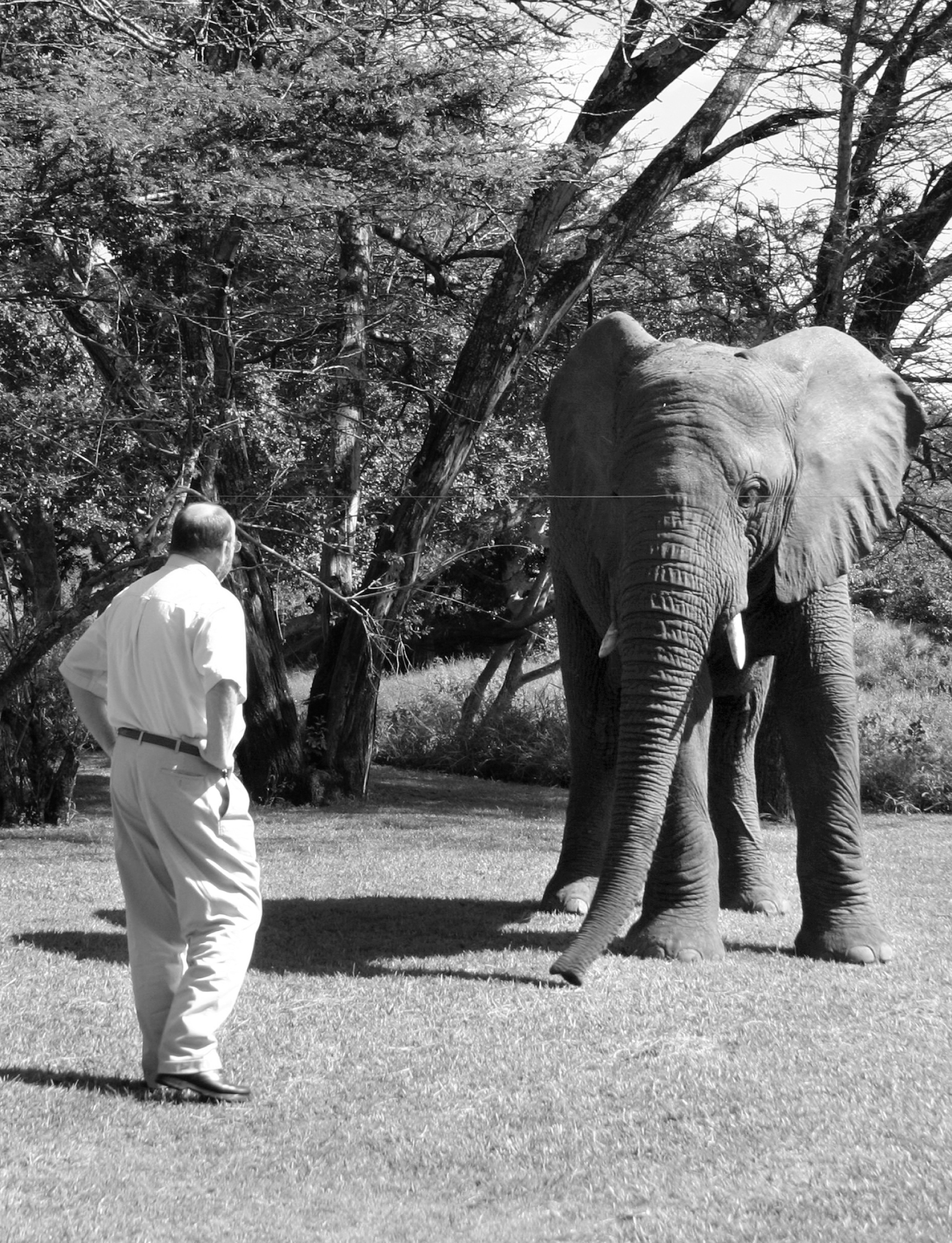

To be clear, the title of this book is not about me. I make no claim to having any special abilities. Rather, it is about the elephantsthey whispered to me and taught me how to listen.

When I describe how the elephants reacted to me, or I to them, it is personal. It is the truth of my own experiences, not the results of planned experiments. I am a conservationist, working to protect wild animals and natural environments. It was through trial and error that I found out what worked best for me and my herd.

Not only am I a conservationist, I am an extremely lucky one. Thula Thula is five thousand acres of undeveloped bush in the heart of Zululand, South Africa. It is the natural home to many local wildlife. This includes the majestic white rhino, Cape buffalo, leopard, hyena, giraffe, zebra, wildebeest, crocodile, lynx, serval, and many species of antelope. We have seen pythons as long as trucks, and we have possibly the largest breeding population of white-backed vultures in the area.

And, of course, now we have elephants. My elephants were the first wild ones to be reintroduced into our area in more than a century.

I cannot imagine life without them. I dont want a life without them. To understand how they taught me so much, you have to know that communication in the animal kingdom is as natural as a breeze. It was only my own human limitations that got in my way of understanding them at first.

In our noisy cities we tend to forget the things our ancestors knew on a gut level: that the whispers of the wilderness are there for all to hearand to respond to.

We also have to understand that there are things we cannot understand. Elephants possess qualities and abilities well beyond the means of science to decode. Elephants cannot use computers, but they do have superior communication abilities.

My herd showed me that compassion and generosity of spirit is alive and well in the pachyderm kingdom. They showed me that elephants are emotional, caring, and extremely intelligent. They showed me, too, that they value good relationships with humans.

These elephants taught me that all life-forms are important to one another in our common quests for survival and happiness. That there is more to life than just yourself, your own family, or your own kind.

1999

Crack! I heard a rifle go off in the distance.

I jumped out of my chair. Then came a burst crack-crack-crack. Flocks of squawking birds flew off.

Poachers. On the western boundary.

David, my game ranger, was already sprinting for the Land Rover. I grabbed a shotgun and leapt into the drivers seat. Max, my Staffordshire bull terrier, scrambled onto the seat between us.

As I turned the ignition key and floored the accelerator, David grabbed the two-way radio.

Ndonga! he bellowed. Ndonga, are you receiving? Over!

Ndonga was the head of my Ovambo guards and a good man to have on your side in a gunfight. But only static greeted Davids attempts to contact him. So we powered on alone.

Poachers had been our biggest problem ever since my then-fiance, Franoise, and I had bought Thula Thula. I couldnt work out who they were or where they were coming from. I had spoken with the izinduna , the headmen, of the surrounding Zulu groups. They firmly stated that their people were not involved. I believed them. They also claimed our problems were coming from inside the reserve, but I didnt think that could be true. I had found our employees to be extremely loyal.

It was almost twilight. I slowed as we approached the western fence, killed the headlights, and pulled over behind a large anthill. We eased through a cluster of acacia trees, our nerves on edge, trigger fingers tense, watching and listening. As any game ranger in Africa knows, professional poachers will shoot to kill.

The fence was just fifty yards away. Poachers like to have their escape route open. I motioned to David. He would keep watch while I crawled to the fence to cut off the poachers retreat if a firefight broke out.

The smell of gunshot spiced the evening air. It hung like a veil in the silence. In Africa, the animals in the bush are only quiet after gunshots.

After a few minutes of absolute stillness, I switched on my flashlight and swept its beam up and down the fence. There were no cuts in it, no holes made by a poacher to get in. And there were no tracks or blood trail to indicate that an animal had been killed and dragged off.

There was nothing but an eerie silence.

Just then, we heard more shots. These came from the eastern edge of the reserve. I realized we had been set up.

Someone had shot off a gun outside the western edge of the reserve to get us to come this way. Now the poachers were shooting nyalabeautiful antelopeson the far side, at least a forty-five-minute drive away.

We jumped back into the Land Rover and sped off, but I knew it was pointless. The poachers would be off the reserve before we even got close.

I now knew, though, that this was a well-organized criminal operation led by someone who followed our every move. The izinduna were right. It had to be someone from the inside. How else could they have timed everything so perfectly?

It was pitch-dark when we arrived at the eastern edge of the reserve and traced the scene with our flashlights. We could see flattened, bloodstained grass from where two nyala carcasses had been dragged to and through a hole in the fence. The hole had been crudely hacked with bolt cutters. About ten yards outside the fence were the muddy tracks of a vehicle. That vehicle would, by now, be miles away. The animals would be sold to local butchers who would use them for biltong, a dried meat jerky, which is very popular throughout Africa.