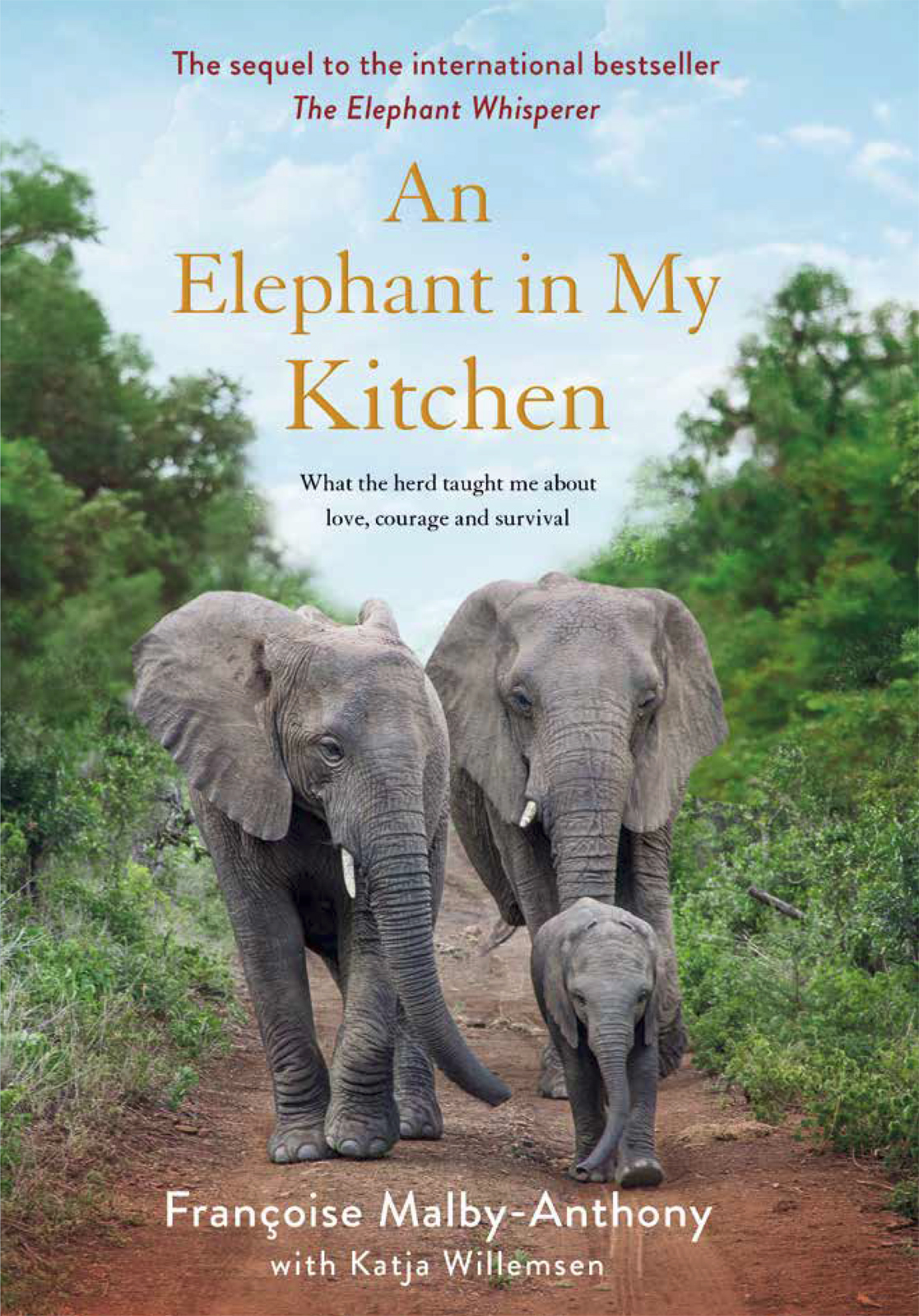

Franoise Malby-Anthony with Katja Willemsen

An Elephant in My Kitchen

What the herd taught me about love, courage and survival

SIDGWICK & JACKSON

To my Thula Thula wild and human family,

thank you for your love and support,

and for giving me the strength

to never give up.

Contents

The only walls between humans and elephants are the ones we put up ourselves

Violent weather always unsettled our elephants, and the predicted gale-force winds meant there was a danger of trees blowing over and causing breaches in Thula Thulas perimeter fence. The cyclone had threatened for days, and while we desperately needed water after a scorching summer, we definitely didnt need a tropical storm. We were worried about the herd, but my husband Lawrence and I were confident that, somewhere in the vast expanse of our game reserve, they had been led to safety by their new matriarch, and my namesake, Frankie.

We hadnt seen them near the house in a while and I missed them.

Whenever they visited, their trunks immediately curled up to read our house. Were we home? Where were the dogs? Was that a whiff of new bougainvillea?

Bijou, my Maltese poodle and sovereign princess of the reserve, hated losing her spot centre stage and always yapped indignantly at them. The adult elephants ignored her, but the babies were as cocky as she was, and would gleefully charge her along the length of the wire fence that bordered our garden, their bodies a gangly bundle of flapping ears and tiny swinging trunks.

No matter how much we treasured their visits, we knew it wasnt safe for them to be this comfortable around humans. The risk of poachers taking advantage of their trust was too high so we planned to slowly wean them off us, or to be more accurate, wean ourselves off them. Not that Lawrence would dream of giving up his beloved Nana, the herds original matriarch; theirs was a two-way love affair because Nana had no intention of giving him up either.

They met in secret. Lawrence would park his battered Land Rover a good half kilometre away from the herd and wait. Nana would catch his scent in the air, quietly separate from the others and amble towards him through the dense scrubland, trunk high in delighted greeting. He would tell her about his day and she no doubt told him about hers with soft throaty rumbles and trunk-tip touches.

What a difference to the distressed creature that had arrived at Thula Thula back in 1999! We had only just bought the game reserve a beautiful mix of river, savannah and forest sprawled over the rolling hills of Zululand, KwaZulu-Natal, with an abundance of Cape buffalo, hyena, giraffe, zebra, wildebeest and antelope, as well as birds and snakes of every kind, four rhinos, one very shy leopard and three crocodiles.

We were very disappointed when we discovered afterwards that the owner had sold off the rhinos. At that point, there werent any elephants either and they certainly werent part of our plan. Not yet; definitely not so soon.

So when a representative of an animal welfare organization asked us to adopt a rogue herd of elephants, we were flabbergasted. We knew nothing about keeping elephants, nor did we have the required boma secure enclosure within the reserve where they could stay until they adjusted to their new life with us.

The woman must know we dont have any experience, I said to Lawrence. Why us?

Probably because no one else is stupid enough; but Frankie, if we say no, theyre going to be shot, even the babies.

I was horrified. Phone her and say yes. Well make a plan somehow. We always do.

Two weeks later, in the middle of a night of torrential rain, three huge articulated trucks brought them to us. When I saw the size of the vehicles, I was hit by the full impact of what was arriving. Two breeding adult females, two teenagers, and three little ones under the age of ten. We knew enough about elephants by then to know that if there were going to be problems, theyd come from the older ones. Lawrence and I exchanged glances. Let the boma hold.

Just as the trucks pulled up at the game reserve, a tyre exploded and the vehicle tilted dangerously in the mud. My heart froze at the elephants terrified trumpeting and screeching. It was only at dawn that we managed to get them into the safety of the new enclosure.

They werent there for long.

By the next day, they had figured out a way to avoid the electric fences brutal 8,000 volts by pushing a nine-metre-high tambotie tree onto it. The wires shorted and off they went, heading northwards in the direction of their previous home. Hundreds of villages dot the hills and valleys around our game reserve so it was a code-red disaster.

We struggled to find them. Youd think it would be easy to find a herd of elephants, but it isnt. Animals big and small instinctively know how to make themselves disappear in the bush, and disappear they did. Trackers on foot, 44s and helicopters couldnt find them. Frustrated with doing nothing, I jumped into my little Tazz and hit the dirt roads to look for them, with Penny, our feisty bull terrier, as my assistant.

Sawubona, have you seen seven elephants? I asked everyone I passed in my best Zulu.

But with a French accent that butchered their language, they just stared at the gesticulating blonde in front of them and politely shook their heads.

It took ten days to get the herd back to Thula Thula. Ten long, exhausting days. We survived on adrenalin, coffee and very little sleep. How Lawrence managed to prevent them from being shot was a miracle. The local wildlife authority had every right to demand that the elephants be put down. They had human safety issues to consider, and besides, they knew only too well that the chances of rehabilitating the group were close to zero. We were warned that if they escaped again, they would definitely be shot.

The pressure to settle them down was terrible and my life changed overnight from worrying about cobras or scorpions in my bedroom to lying awake, waiting for Lawrence to come home, scared stiff he was being trampled to death in his desperation to persuade the elephants to accept their new home. Night after night, he stayed as close to the boma as he dared, singing to them, talking to them and telling them stories until he was hoarse. With tender determination and no shortage of madness, Lawrence breached Nanas terror of man and gained her trust.

One hot afternoon, he came home and literally bounced up the steps towards me.

You wont believe what happened, he said, still awestruck. Nana put her trunk through the fence and touched my hand.

My eyes widened in shock. Nana could have slung her trunk around his body and yanked him through the wires.

How did you know she wouldnt hurt you?

You know when you can sense someones mood without a word being spoken? Thats what it was like. She isnt angry any more and she isnt frightened. In fact, I think shes telling me theyre ready to explore their new home.

Please get out of this alive, I begged.

Were over the worst. Im going to open the boma at daybreak.

That night, Lawrence and I sat on our veranda under a star-flung sky and clinked champagne glasses.

To Nana, I sighed.

To my baba, Lawrence grinned.

The herd had become family over the past thirteen years, so we were extremely worried when the storm warnings worsened and the risk of the cyclone smashing into us increased with every passing hour.

Lawrence was away on business and I was on my own. He called me non-stop.