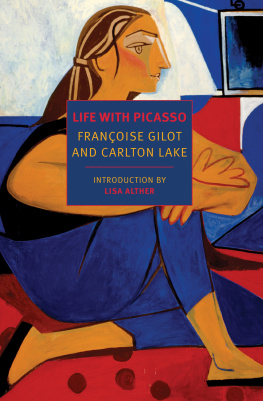

FRANOISE GILOT (b. 1921) was born in Paris to an agronomist father and an artist mother. Having decided to be a painter at the age of five, she began her training in art while still in her early youth. She later studied law at her fathers insistence but returned to painting during the Second World War. Because of the censorship of art in Nazi-occupied France, Gilots early work relied heavily on symbols. In 1943 she met Pablo Picasso and they lived together for ten years. They had two children: Claude, born in 1947, and Paloma, born in 1949. In 1950, the art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler took Gilot under contract at his gallery. After leaving Picasso in 1953, Gilot rekindled a friendship with the surrealist painter Luc Simon. They were married in 1955 and their daughter, Aurlia, was born the following year, though the couple would separate in 1961. Gilot began exhibiting in the United States in the early 1960s and in 1962 the Tate Gallery provided her a studio in London where she painted an abstract series about the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. In 1969, after an exhibition in Los Angeles, she met Jonas Salk; they were married in 1970 and lived and worked in California, Paris, and New York until Salks death in 1995. Gilots American period is marked by a bold use of color and movement. In addition to painting, Gilot has written several books, including Interface: The Painter and the Mask (1975), the biography Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art (1990), and, with Lisa Alther, About Women: Conversations Between a Writer and a Painter (2016). Her art is in the collections of, among other museums, MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Pompidou Center; she has shown around the world, including a 2012 dual exhibition with Picassos work at the Gagosian Gallery in New York and a series of retrospectives from 2010 to 2012 in Japan, Hungary, Germany, and the United States. She was made an Officer of the Lgion dHonneur in 2009.

CARLTON LAKE (19152006) was an art critic, curator, and collector. He was the Paris art critic for The Christian Science Monitor and contributed art criticism to a number of publications, including The New Yorker and The Atlantic. After returning to the United States in 1975, he became the curator of the French Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, where he had donated his extensive collection of French art, manuscripts, and music. His other books include A Dictionary of Modern Painting (1956), In Quest of Dal (1969), and Confessions of a Literary Archaeologist (1990).

LISA ALTHER is the author of seven novels, a memoir, a short-story collection, and a narrative history. In addition to writing About Women with Franoise Gilot, Althers novella Birdman and the Dancer is illustrated with monotypes by the artist.

LIFE WITH PICASSO

FRANOISE GILOT

and CARLTON LAKE

Introduction by

LISA ALTHER

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1964 by Franoise Gilot and Carlton Lake

Introduction copyright 2019 by Lisa Alther

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Franoise Gilot, Self-Portrait, 1953; courtesy of the artist

Cover design: Katy Homans

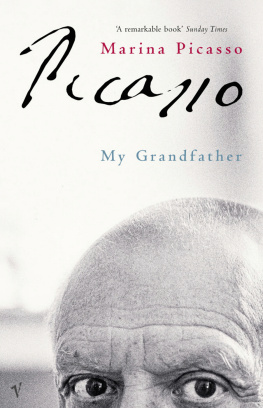

Frontis: Robert Capa, Pablo Picasso and Franoise Gilot at Their Home, 1951; copyright by the International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

The publishers would like to thank Aurlia Engel for her assistance in the publication of this volume.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gilot, Franoise, 1921 author. | Lake, Carlton, author.

Title: Life with Picasso / by Franoise Gilot and Carlton Lake. Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] | Series: New York Review Books Classics | Originally published: New York : McGraw-Hill, c1964.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018025719| ISBN 9781681373195 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681373201 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Gilot, Franoise, 1921 | Picasso, Pablo, 18811973. | PaintersFranceBiography.

Classification: LCC ND553.P5 G55 2019 | DDC 759.4 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018025719

ISBN 978-1-68137-320-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I FIRST encountered Franoise Gilot as a painter, not a writer, at an exhibition of her work in Paris in 1986. Small and slender with excellent posture and intense green eyes, she was friendly and funny. She also struck me as a powerful person, an impression her paintings reinforced with their bold shapes and vibrant colors.

A couple of years later I came across her memoir Life with Picasso. Although of course aware of Pablo Picassos status as a demigod in the art world, I read the book from an interest in its author rather than its subject. What most impressed me, as a writer myself, was how well written it was. Although French was Gilots first language, she had composed the book in a much better English than most of us native English speakers can usually muster. Once I got to know her, I asked her about this, and she replied that she has written all her books, of which there are now a dozen, in English because she prefers the shorter sentences. French sentences can run on for an entire page, she explained, including many unnecessary details and qualifications, whereas English sentences are usually more crisp and succinct. She also mentioned that the nuns in her convent school were so severe in their criticisms that she feels less inhibited when writing in English, which she learned in school and during childhood summers in England.

Gilot also expressed gratitude to Carlton Lake, an American journalist listed as her co-author on Life with Picasso, for persuading her to undertake the book and for handling the technical aspects of the projectthe taping and typing. They met three afternoons a week for a couple of years, on the first afternoon taping Gilots recollections of her relationship with Picasso. The next day she would rework the typescript, and on the third day she would review the edited episodes and place them within the text.

When Life with Picasso was published in 1964, it generated a lot of controversy. Picasso launchedand lostthree lawsuits trying to prevent its publication. Some forty French artists and intellectuals, many presumed champions of free speech, many former friends of Gilot when they believed she could smooth their pathway to Picasso, signed a manifesto demanding that the book be banned. They evidently found it acceptable for Picasso to have used Gilots likeness in hundreds of his artworksbut scandalous if she portrayed him in hers. In that preMe Too era, women were not supposed to bite the tires of the Humvees that were rolling over them.

More than fifty years later, I have difficulty comprehending the objections to this book, since Picasso emerges from its pages as the supremely gifted artist that he undoubtedly was. His methods and rationales regarding his painting and drawing are lucidly described, as are his groundbreaking excursions into etching, lithography, sculpture, and pottery. Gilot makes it clear that he was a genius of invention and a force of nature, someone whose compulsive creativity was constantly percolating. He deconstructed and reconfigured everything he encountered, including the works of old masters as well as those of his own contemporaries. His goal seemed always to dismantle stale visual clichs and to employ familiar forms in unusual ways, in order to stimulate fresh perceptions and emotions in his viewers. Picasso also comes across in the book as an amusing character at times, with an antic sense of humor.

Next page