Table of Contents

Praise for the Fate of Africa

A welcome and significant contribution to the local and global debate about the state of the continent.

AllAfrica.com

Though today an independent scholar, Meredith was one of those now-too-rare journalists who knew his beat intimately, having lived on and off (mostly on) in Africa for 40 years, informing a keen and humane mind with all things African. It shows here in the depth and fluid familiarity of his narrative, light on its feet for so wildly complex a picture. Meredith isnt afraid of venturing an opinion, but what he dines on are basic realities: who did what when, and the consequences. These he spreads before his readers, for them to draw their own, now also informed, conclusions.

San Francisco Chronicle

For the author, even organizing this information is a hugely daunting job. How can such vast amounts of information be analyzed for the reader? One way was to follow parallel developments in different placeswhich is more or less how Mr. Meredith works, with attention to the hair-trigger ways in which one coup or crisis could set off subsequent disasters. He is able to steer the book firmly without compromising its hard-won clarity.

New York Times

A solid journalistic and analytical recounting of recent African history with a hard, dispassionate eye without an ideological edge... The Fate of Africa ... is a big, important book that, although at times benumbing in its litany of horror and hopelessness, desperately deserves to be widely read and discussed.

Indianapolis Star

The Fate of Africa is a comprehensive, wonderfully readable survey of the entire continents recent past.... Blessed with a strong, clean prose style, the author has delivered a work that offers an education in one volume and, despite its length, the book maintains the pace of an artful novel....

Ralph Peters, New York Post

Meredith first traveled up the Nile from Cairo in 1964 as a 21-year-old and claims that, in many ways, his African journey has continued ever since. His careful, detailed analysis, his dispassionate but not detached writing, and his evident wit mean that we might all hope his journey continues for much longer.

The Weekly Standard

Merediths exhaustive study appears just as world leaders are finally trying to come to grips with Africas needs. It starkly underlines the urgency of that task.

Providence Journal

In this book [Meredith] provides the most comprehensive description of the causes and consequences of failure in quite a while.

Boston Globe

The book is elegantly written as well as unerringly accurate, and despite its considerable length it holds the attention of the reader to the end.

Financial Times

[Merediths] massive but very readable examination of African history over the past century unfolds like a drawn-out tragedy... This is a brilliant and vitally important work for all who wish to understand Africa and its beleaguered people.

Booklist starred review

Complex, but highly accessible... Sharp-edged, politically astute.

Kirkus Reviews

In Africa the past does matter. It explains the present and no one is going to move anywhere without it. That is why this book is important. Its about how we got here. The legions of development missionaries, trained in development theory, heading off to Africas capitals to work in air-conditioned offices, should all be given a copy free. The book is also a great narrative. Delivered in digestible chunks, it plots the politics of independent Africa country by country. Meredith is at his best telling the story of the rise and fall of each ruler. African potentates are nothing if not dramatic... Meredith has given a spectacularly clear view of the African political jungle.

Richard Dowden, Spectator

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi Out of Africa always something new

AUTHORS NOTE

I n 1964, at the age of twenty-one, I set out from Cairo travelling up the Nile on a journey to central Africa. In many ways, my African journey has continued ever since. As a young reporter on the Times of Zambia , I was fortunate enough to witness the surge of energy and enthusiasm that accompanied independence. As a foreign correspondent based in Africa for fifteen years, my experience was more often related to wars, revolution and upheaval. As a research fellow at St Antonys College, Oxford, and as an independent author, I sought deeper perspectives on modern Africa. Along the way I have met with much generosity and goodwill. Many people on many occasions have given me valued help and assistance. To list them here would cover too many pages. But for the innumerable acts of kindness, of hospitality and of friendship I have received, I am profoundly grateful. What has always impressed me over the years is the resilience and humour with which ordinary Africans confront their many adversities. This book is intended as testimony to their fortitude.

INTRODUCTION

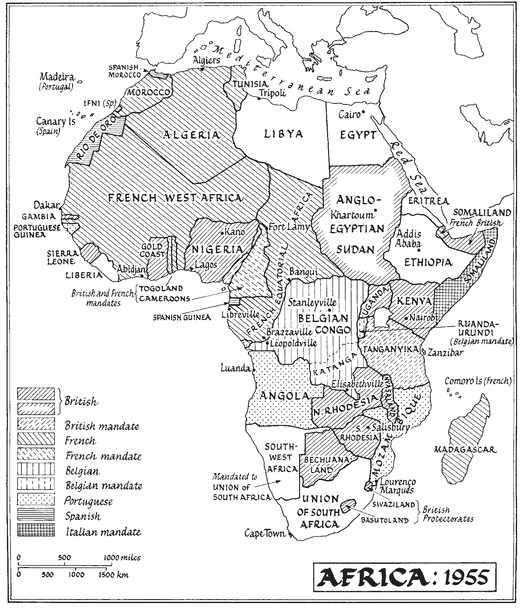

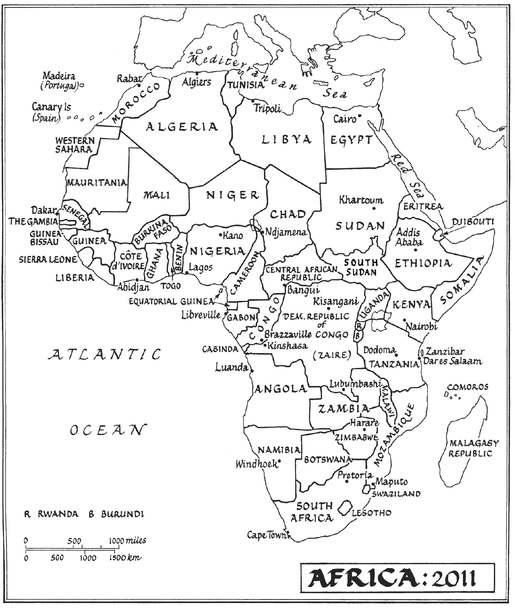

D uring the Scramble for Africa at the end of the nineteenth century, European powers staked claims to virtually the entire continent. At meetings in Berlin, Paris, London and other capitals, European statesmen and diplomats bargained over the separate spheres of interest they intended to establish there. Their knowledge of the vast African hinterland was slight. Hitherto Europeans had known Africa more as a coastline than a continent; their presence had been confined mainly to small, isolated enclaves on the coast used for trading purposes; only in Algeria and in southern Africa had more substantial European settlement taken root.

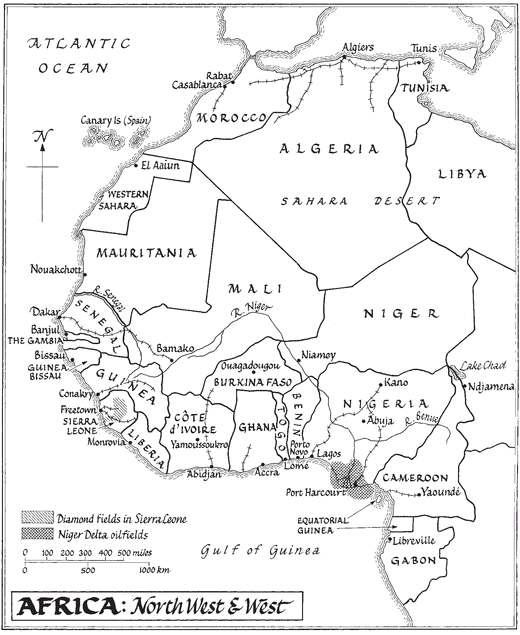

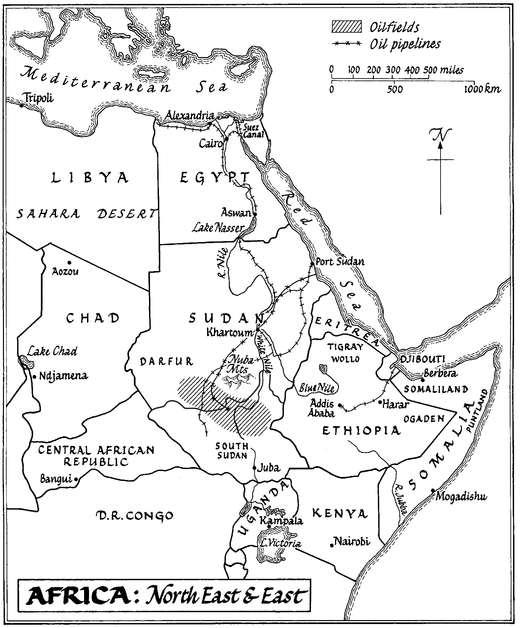

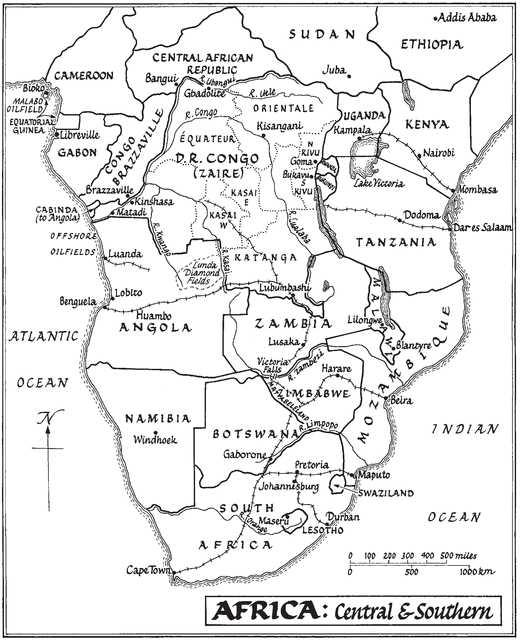

The maps used to carve up the African continent were mostly inaccurate; large areas were described as terra incognita . When marking out the boundaries of their new territories, European negotiators frequently resorted to drawing straight lines on the map, taking little or no account of the myriad of traditional monarchies, chiefdoms and other African societies that existed on the ground. Nearly one half of the new frontiers imposed on Africa were geometric lines, lines of latitude and longitude, other straight lines or arcs of circles. In some cases, African societies were rent apart: the Bakongo were partitioned between French Congo, Belgian Congo and Portuguese Angola; Somaliland was carved up between Britain, Italy and France. In all, the new boundaries cut through some 190 culture groups. In other cases, Europes new colonial territories enclosed hundreds of diverse and independent groups, with no common history, culture, language or religion. Nigeria, for example, contained as many as 250 ethnolinguistic groups. Officials sent to the Belgian Congo eventually identified six thousand chiefdoms there. Some kingdoms survived intact: the French retained the monarchy in Morocco and in Tunisia; the British ruled Egypt in the name of a dynasty of foreign monarchs founded in 1811 by an Albanian mercenary serving in the Turkish army. Other kingdoms, such as Asante in the Gold Coast (Ghana) and Loziland in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) were merged into larger colonial units. Kingdoms that had been historically antagonistic to one another, such as Buganda and Bunyoro in Uganda, were linked into the same colony. In the Sahel, new territories were established across the great divide between the desert regions of the Sahara and the belt of tropical forests to the south Sudan, Chad and Nigeria throwing together Muslim and non-Muslim peoples in latent hostility.