Table of Contents

ALSO BY MARTIN MEREDITH:

The Past Is Another Country: RhodesiaUDI to Zimbabwe

The First Dance of Freedom: Black Africa in the Postwar Era

In the Name of Apartheid: South Africa in the Postwar Era

Coming to Terms: South Africas Search for Truth

Elephant Destiny: Biography of an Endangered Species in Africa

Mugabe: Power, Plunder, and the Struggle for Zimbabwe

The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence

Diamonds, Gold, and War:

The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa

For T

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN THE YEARS THAT I HAVE BEEN WRITING ABOUT SOUTH AFRICA, AS a journalist and as an author, I have encountered much generosity and goodwill. Many people on many occasions have given me valued help and assistance and shown great hospitality. For all the acts of kindness I have received, I am profoundly grateful. I would like here to record my thanks in particular to Nelson Mandela and to his friends and colleagues who were so forthcoming about him. I am especially grateful to Walter Sisulu, and to Beryl Baker, Fikile Bam, Mary Benson, Hilda Bernstein, Rusty Bernstein, George Bizos, Nat Bregman, Amina Cachalia, Yusuf Cachalia, Ilse Fischer, Ruth Fischer, Bob Hepple, Rica Hodgson, Joel Joffe, Adelaide Joseph, Paul Joseph, Kathy Kathrada, Wolfie Kodesh, Mac Maharaj, Govan Mbeki, Godfrey Pitje, Lazar Sidelsky, Joe Slovo, Ben Turok and Harold Wolpe. My thanks are also due to librarians at the William Cullen Library and Jan Smuts House Library, University of the Witwatersrand, at The Star, Johannesburg, and at Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. I am also grateful to Penny Hoare, for her early encouragement of the work; to Christina Hardyment, Heidi Holland, Felicity Bryan, Kate Jones, and Antonia Till; and to Rachel Whitehead, for providing the rural retreat where this book was written.

PROLOGUE

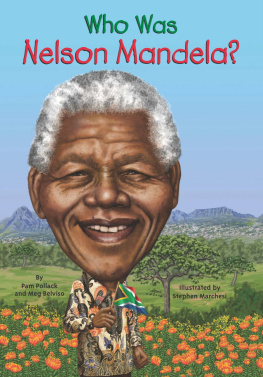

WHEN NELSON MANDELA WALKED THROUGH THE GATES OF VICTOR Verster prison in 1990, hand-in-hand with his wife, Winnie, it was a moment of liberation experienced around the world. Sentenced to life imprisonment in 1964 for his role in trying to overthrow South Africas apartheid government, Mandela had languished as a prisoner on Robben Island largely forgotten for more than a decade. During the harsh days in the Seventies, Mandela recalled, we had to force ourselves not to give in to despair. But during the 1980s, as the anti-apartheid movement gathered momentum both in South Africa and abroad, Mandela became a potent symbol of resistance. The campaign for his release was taken up in one country after another. Awards were showered upon him by foreign governments, by universities and by cities; streets were named after him; songs were written about him; his deeds were celebrated at rock concerts. Yet millions of people who supported the campaign had only scant understanding of who he was. Nor did anyone have a clear idea of what he now looked like: no new photograph of him had been published since 1964. Incarcerated in prison, Mandela gained mythical statusthe lost leader whom the world yearned to see again.

Behind the faade of fame, Mandela remained at times an enigmatic figure. Prison colleagues who were his companions for years on end sometimes felt they did not really know him. He emerged from prison an intensely private person, accustomed to concealing his emotions behind a mask. He confided in few people. He disliked familiarity. The grip of self-control he acquired in prison rarely left him. His habits remained austere. He did not drink or smoke, and he never swore. At the state residences he occupied in Cape Town and Pretoria after the 1994 election, his housekeepers were well versed in his liking for neatness and order. As president, he continued to make his own bed.

Yet prison life did not rob him of either his charm or his civility. The radiance of his smile was undiminished. He possessed a natural authority and charisma, evident to all who encountered him. Despite his patrician nature, he retained the common touch. His manners were punctilious, reminiscent of another, more gracious age. He was courteous and attentive to individuals, whatever their status or age, often stopping to talk with genuine interest to children or youths. He greeted workers and tycoons with the same politeness. Indeed, he sometimes seemed more at ease with strangers than in the company of friends.

As president, he managed not only to sustain his popularity among the black population he had fought to liberate from white rule but also to gain the respect and admiration of the white community which had once reviled him. His efforts to overcome the deep racial divisions afflicting South Africa earned him universal acclaim. As a mark of his standing, the name by which he became affectionately known, by black and white alike, was Madiba, his clan name, which dated from an eighteenth-century chief. National sporting victories in rugby, soccer and cricket were sometimes attributed to Madiba magic, the effect of his presence among the spectators. Mandela enjoyed the fame, but remained unmoved by it and became increasingly conscious of the gap between his public image and the ordinary man he felt himself to be.

His nature was not always benign. He was feared as well as revered. He tended to be autocratic. At times he wielded his massive authority unwisely. In old age he was as capable of acting impetuously as in the days of his youth. He was still renowned on occasion for his stubbornness and quick temper. His face sometimes settled into an inscrutable, sphinx-like stare, the lines and furrows on it marking his displeasure.

Despite the ailments of old age, he brought to his years as president remarkable energy, as if anxious to make up for lost time. Approaching his eightieth year, he usually rose before dawn, relishing the prospect of an early-morning walk, devouring newspapers and telephoning colleagues long before the normal working day began. Amid an endless stream of meetings, speeches and official functions, he nevertheless ensured he had time to respond to individual requests, readily accepting invitations from schoolchildren and from ordinary citizens, telephoning strangers when the occasion arose and making himself available for snapshots. But while enjoying contact with common people, the company to which he was most attracted was that of the rich and famous; status impressed him.

The relentless pace he set himself took its toll. He succumbed occasionally to bouts of exhaustion. Constant plane travel exacerbated a hearing problem. His ankles were perennially swollen. He walked with an increasingly stiff gait. The eye affliction he had acquired from years of working in the harsh glare of the lime quarry on Robben Island gave him chronic trouble. The burdens of office sometimes seemed too onerous. One gets used to it, but it destroys your family life. I miss childrenjust being able to be with children at the end of the day and listen to them chatter.