Its impossible to make small talk with an icon

Which is why, to find my tongue,

I stare down at those crunched-up

One-time boxers knuckles.

In their flattened pudginess I find

Something partly reassuring,

Something slightly troubling,

Something, at least, not transcendent.

Jeremy Cronin, 1997

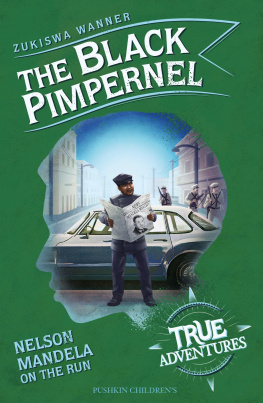

The South African cartoonist Zapiro celebrated Nelson Mandelas eightieth birthday with a scene called Nelson Mandela: The Early Years. An African primary school teacher, holding sheets of paper her tiny wards have handed in, confides to a colleague: This one cant make up his mind: he put down lawyer, activist, freedom fighter, prisoner of conscience, president, reconciler, nation-builder, visionary and 20th century icon. Zapiros homage not only provides a thumbnail sketch of a famous career but also hints at the dilemma confronting anyone writing a short biography of the man. So many aspects of Mandelas life are familiar that they challenge a biographer to find fresh meaning in them: the rural childhood, an early adulthood shaped by opposition to apartheid, a watershed decision to take up arms, a famous trial and a life sentence; and after twenty-seven years in jail, a remarkable policy of reconciliation and his election as the first president of democratic South Africa.

Consider, too, the quite extraordinary veneration and affection he won from people across the world never more obvious than in the torrent of tributes and avalanche of encomia that greeted his death. How does any observer sift the actual life of an individual from the idealised hero: a secular saint, symbol not only of his own nations rebirth but moral leader of humankind, whose death reminded a world of its hunger for hope, for a better future? How does one trace the tentative steps, mistakes and mishaps, the flaws and failures which are the lot of any human life from an air-brushed, formulaic, eulogised life-story that seems to transcend mortal measures?

There is an element of retrieval involved in a posthumous Mandela biography, however brief: an attempt to rescue the man from the myth. After all, what was the legacy of the man who died in December 2013? Those who rushed to wrap themselves in Mandelas mantle included Havana and the White House, Israelis and Palestinians, the Vatican and ayatollahs, Chinese government and Chinas dissidents and countless others across every political spectrum. Does any death so universally mourned not require a life and its achievements to have been universalised and sanitised, stripped of complexity, hallowed and hollowed, remade as an identikit icon? And if so, the challenge is to arrive at a biographical narrative that recognises Mandela as a compelling and complex political actor, but subject to the kinds of constraints and contradictions that describe any career.

So this biography locates Mandela in his time and place, indicating the social and political currents that bore him. It reminds readers of a point made frequently by Mandela himself: that his own achievements were part of broader, collective efforts and that they cannot be otherwise understood. And it shows that his political efforts and those of the African National Congress (which he served for seventy years) involved the compromises, short cuts and shortcomings that are intrinsic to any politics in a complex world.

To write a biography that eschews hagiography is not an attempt to belittle Nelson Mandela, nor to carry out some sort of hatchet job on his reputation. Mandelas stature as a giant is beyond question. As nationalist leader, his place in his countrys history is comparable to those of Atatrk, Nasser, Nehru, Nkrumah, Sukarno and Ho Chi Minh; as exemplar of moral and civic virtues, he ranks with Lincoln, Gandhi and Martin Luther King (although he did not share the last twos adherence to non-violence as a principle); as a twentieth-century public figure who inspired love and respect, he belonged to a tiny club including perhaps Pope John XXIII, Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama. Mandela observed J.M. Coetzee was, by the time of his death, universally held to be a great man: he may well be the last of the great men, as the concept of greatness retires into the historical shadows.

Yet the conundrum persists: how much of his towering reputation derived directly from Mandela-the-man, his principles and practice, his deeds and words and how much was the product of a constructed version, Mandela-the-myth, an image deliberately burnished for political purposes? It is worth reflecting that Mandelas place in history is guaranteed by his role after his release in February 1990; the man who walked into the transfixed gaze of the global media that Sunday afternoon was already a legend. He was the worlds most famous political prisoner; he was absent, yet imminently present; his silence reverberated. He had acquired an almost posthumous eminence, showered with honorary degrees and prizes.

How does one explain so singular a renown? In order to answer this question, this biography does not begin with Mandelas childhood and then trace his life throughout ninety-five years; instead, it commences with a history of Mandela-the-myth, the making of the icon, and then resumes the more conventional form of a life history.

Notes

Cronin, J., Poem for Mandela, from Even the Dead: Poems, Parables and a Jeremiad (David Philip, 1997), p.30.

Coetzee, J.M., On Nelson Mandela (19182013), New York Review of Books , 9 January 2014.

Nixon, R., Homelands, Harlem and Hollywood: South African Culture and the World Beyond (Routledge, 1994), p. 176.

1

Man and Myth:

The Construction of an Icon

21 years in captivity

Are you so blind that you cannot see?

Are you so deaf that you cannot hear?

Are you so dumb that you cannot speak? I say

Free Nelson Mandela

Free Nelson Mandela

Free Nelson Mandela

The Special A.K.A., 1984

The day before Mandela died, the Cape Times Cape Towns morning newspaper carried two short news stories separated by a photograph captioned Our Icon. The first item reported that a photographic portrait of Nelson Mandela had been sold for a record $200,000. The portrait, by Adrian Stern, was sold to a New York private collector who wished to remain anonymous.

The second story reported the announcement in Johannesburg of a book in production the Nelson Mandela Opus . The book would be half a metre square and weigh 37 kilograms. Only 10,000 copies would be available worldwide although derivatives would be more widely available. The book, in burnished leather covers, was being produced by Opus Media, self-badged as the foremost luxury publishing brand. It was the latest title in a series on iconic organisations and personalities, which include brands such as Formula One, Ferrari, Manchester United, Michael Jackson, Sachin Tendulkar and the Springboks.

This chapter is not about Mandela as a brand, or as a commodity; yet the pricey portrait and the brazen excesses of the Opus project cannot be comprehended without some sense of the construction, over several decades, of an iconic Mandela. In the years from 1950 to 1990 the person of Mandela became the vehicle for an increasing freight of symbolic meaning. Many hands were involved in the enterprise, adding details, heightening the lustre, positioning the heroic subject in ever more favourable light. But crucial contributions to the project, in the 1950s and early 1960s, were made by Mandela himself.

All the major commentators on Nelson Mandela have noted his acute awareness of his own presence, of the potency of the image and the strength of the symbolic gesture or stance. Elleke Boehmer writes of his chameleon-like talent for donning different disguises; his theatrical flair for costume and gesture; his shrewd awareness of the power of his own image. Tom Lodge places special emphasis on Mandelas political actions as performance, self-consciously planned, scripted to meet public expectations, or calculated to shift popular sentiment For Mandela, politics has always been primarily about enacting stories, about making narratives.