In the seventh year of Nelson Mandelas captivity, a notoriously brutal commander took over the prison on Robben Island . By then, Mandela and his fellow inmates had softened and even befriended some of their guards. Working conditions in the lime quarry had grown less harsh, and they were allowed study privileges. South Africas rulers concluded that the fearsome island dungeon was going soft. Colonel Piet Badenhorst was sent to whip the prisoners back into line.

Badenhorst transferred the old guards off the island and replaced them with a new lot younger, coarser, harder. The miserable food got worse. Cells were raided, books and papers were confiscated, and many men were sent to solitary confinement. Badenhorst singled out Mandela as the chief instigator and subdued and provoked him with calculated insults as a lesson to the rest. One bitterly cold night, the prisoners were rousted from sleep by a gang of drunken guards, ordered to strip, and lined up against the wall of the outside courtyard where they stood naked and shivering for an hour until one of them collapsed with chest pains. Such treatment was routine.

The prisoners fought back as best they could, filing complaints that went ignored and smuggling messages to the outside world. In a daring move, Mandela organized a delegation to confront Badenhorst. They threatened work stoppages, slowdowns, and hunger strikes if he didnt ease up. Badenhorst said he would consider what they said and ordered no reprisals. The prisoners counted that a victory.

After several months, apparently in response to the smuggled messages, three judges showed up to conduct an inspection. Mandela, as the prisoners spokesman, met with them under Badenhorsts baleful eye. As Mandela described the beating of a non-political prisoner, the commandant wagged a finger in his face. Be careful, Mandela, he warned. If you talk about things you havent seen, you will get yourself into trouble. You know what I mean.

Mandela turned to the judges. Gentlemen, you can see for yourselves the type of man we are dealing with as commanding officer, he said calmly. If he can threaten me here, in your presence, you can imagine what he does when you are not here. The judges agreed. Within three months, Badenhorst was transferred.

A few days before Badenhorst left, Mandela was again summoned to tell the colonel and South Africas commissioner of prisons if the prisoners had other complaints. Mandela ran down his list. When he finished, Badenhorst spoke like a human being and showed a side of himself we had never seen before. The commandant told Mandela he would soon be leaving and added, to Mandelas astonishment, I just want to wish you people good luck.

Mandela thought about that for a long time. He concluded that Badenhorst wasnt evil, but merely corrupted by an inhuman system that rewarded brutality. It was a reminder, Mandela later wrote, that All men, even the most seemingly cold-blooded, have a core of decency, and that if their hearts are touched, they are capable of changing.

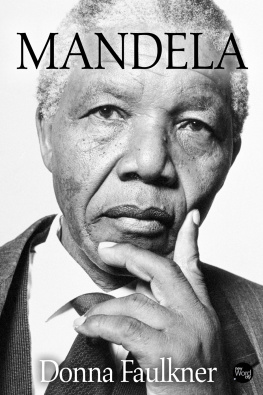

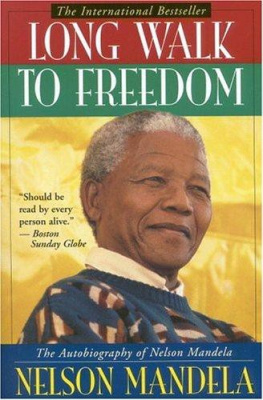

Mandelas experiences and his thoughtful conclusion go a long way toward explaining his near-miraculous success in leading the liberation of his people, ending the vicious system of apartheid , and ultimately reconciling black South Africans with their white oppressors. With his tenacity, his courage and coolness, he confronted power with no better weapons than his words, his logic, and a deep sense of optimism. But the crucial ingredient of his faith was Mandelas certainty that even the worst of people can be redeemed and his willingness to acknowledge even fleeting kindness from his tormentor.

Nelson Mandelas long life was a most remarkable one. From a barefoot child herding cows in a South African village, he became a child of privilege; a rebellious runaway; an impoverished student and father; a successful lawyer; a political idealist and dissident; a rising star in the African nationalist movement; an underground saboteur; the chief defendant in three show trials; a political prisoner; a secret negotiator with South Africas rulers; a Nobel Peace Prize winner and president of his country; and an international statesman who held South Africa together long enough to find reconciliation and the path to prosperity.

But this is Mandela as seen from the outside; some of it is illusion. He saw himself as a pragmatic politician with one fixed goal: the end of white supremacy through votes for everyone. He knew fear and bitterness and often regretted his mistakes, but he learned to hide and subdue his feelings in order to reach his goal. Apart from that one overarching aim, everything else was tactics. If non-violence worked, he was for it; when bombs and guns were winning, he would use them, too. He started or suspended negotiations as the situation demanded and ignored grievances in favor of peace. If the cause required that he sacrifice his freedom and much of his personal life, well, so be it. He was always focused on the prize, and, in the end, he won it and with it, the worlds adulation and the enduring love of his people. This is his story.

In Nelson Mandelas memory, his boyhood was idyllic. He lived in his mothers house, a dirt-floored thatched hut in the tiny village of Qunu, in the Transkei district some 550 miles south of Johannesburg. The villagers grew or raised everything they ate and wore - from beans, pumpkins, sorghum, and the maize used to make mealie pap, a kind of corn pudding, to sheep, goats, and cows, which provided meat, milk, and hides. Mandela played on the veld with the other village boys, gathering wild honey, swimming in clear streams, and drinking milk straight from the cow. He herded calves and sheep and learned the art of leading from the back - ambling behind the animals, subtly steering them in the direction he chose. The technique stayed with him. It is wise, he said decades later, to persuade people to do things and make them think it was their own idea.

On July 18, 1918, Nelson Mandela was born in the village of Mvesa, on the banks of the winding Mbashe River, where life was lived much as it had been for hundreds of years. He was part of a royal family. His great-grandfather, Ngubengcuka, had united the Thembu tribe of the Xhosa nation and had become their king. But Nelsons grandfather, Mandela, was the son of one of the kings lesser wives from a so-called left-hand house; he and his line were ineligible to rule and could only counsel the king. Nelsons father, the tall and stately Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, served as chief of the village of Mvezo and counselor to King Jongilezwe Dalindyebo. But the white government of South Africa maintained that tribal officials be ratified by the local white magistrate, and the proud Gadla considered that requirement an encroachment on tribal authority. He infuriated the magistrate in Mvezo by refusing to show up at a hearing to answer a complaint. Accusing him of corruption, the magistrate ousted Gadla, who subsequently lost most of his land, herd, and income.

Gadla had four wives, and his fall from grace brought hard times for them. To be near relatives, Nelsons mother, Nosekeni Fanny, moved to Qunu, a village of a few hundred people in a narrow, grassy valley dotted by beehive-shaped mud huts.

A Christian convert, Nosekeni sent her son to a Methodist school when he was seven. Though his father had named him Rolihlahla, a Xhosa colloquialism meaning troublemaker, the schoolteacher called him Nelson. Whites were either unable or unwilling to pronounce an African name and considered it uncivilized to have one, Mandela later wrote. Why she bestowed this particular name on me I have no idea.