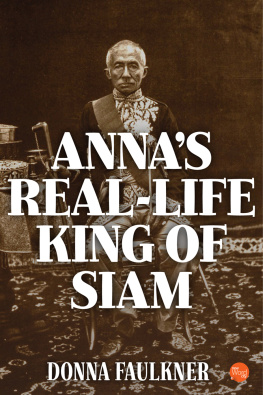

He was the greatest ruler in his countrys history. Inheriting a Siam of medieval customs and feudal ignorance, King Maha Mongkut almost single-handedly lifted it into the nineteenth century. He sparked the reform of Buddhism and spoke eleven languages. He mastered history, geography, astronomy, and the principles of chemistry, physics, and math. He transformed himself from a god-king to the approachable, tolerant father of his people, and in a diplomatic triumph, he played the rapacious European powers against each other so deftly that Siam, alone among the nations of Southeast Asia, never succumbed to colonial dominance.

Thus, his people were more than a little upset when an English governess, Anna Leonowens, cashed in on her five years as a royal tutor and secretary to write two lurid books slandering the king as a capricious barbarian tyrant who burned alive one of his concubines for sleeping with another man. Eight decades later, the country now known as Thailand was even more offended when Broadway and Hollywood twisted the story into the musical The King and I. On stage and screen, Yul Brynner pranced around bare-chested, indulged in imperious tantrums, and tormented Mongkuts quaintly colorful English into a kind of pidgin (Is a puzzlement). Worse, the libel of the errant concubine was central to the plot. In reality, Mongkut was both generous and open-minded - the first Siamese king to free women to leave the harem at will.

Anna Leonowens has few fans in Bangkok; one of the kings biographers denounced her as the perfidious and mendacious governess. But a few of the kings admirers concede that if she hadnt written her sensational books, Mongkut would likely be a forgotten figure outside of Thailand. Today, his cartoonish popular image is offset by his historic record as the unlikely savior of his country. He was, as you are about to read, a thoroughly remarkable man. Here is his story.

A Boy Named Crown

The child who was to bear the royal title Somdetch Phra Pramdendr Maha Mongkut was the grandson of King Rama I , the general who founded the Chakri line of kings that still holds the constitutional monarchy of modern Thailand. Born in 1804, he was the forty-third child of Rama II , who was crowned when Mongkut was five years old. As the son of his fathers principal queen, the boy was seen as the likely heir to the throne. His given name meant crown, and he lived in the vast splendor of Bangkoks Grand Palace . It was a time when kings lived like gods, dressed in jewels and cloth of gold, surrounded by dazzling ornaments and kowtowing servants, riding in gilded barges or on elegant palanquins (litters) or elephants backs. Ordinary mortals were forbidden to look at the monarch. When he traveled with his retinue, people were ordered to shutter their windows, and royal crossbowmen would shoot at anyone caught peeking.

Mongkuts father, an eloquent poet, tutored him personally and provided teachers of Siamese history, religion, and literature, as well as the art of war and the sacred languages of Sanskrit and Pali . But the Siamese, isolated in their jungles, knew nothing of the Western worlds sciences, history, or politics. To them, humans lived only in China or nearby nations; all other lands were inhabited by barbarians or demons. When Mongkut was a boy, one of his biographers wrote, Europe and England were to him then hearsay, and America was mere gossip.

At twelve, Mongkut was initiated as a man and given his own palace and retinue, but his lush life was abruptly interrupted at fourteen, when he followed tradition for boys of good family and entered a monastery as a novice Buddhist monk. For seven months, he lived in austerity, owning only a yellow robe, an iron begging bowl, a needle, and a few other necessities. Each morning, he walked out barefoot to stand in silence with his bowl, waiting for people to fill it with whatever food they could offer, which he then ate without complaint. He accepted this with religious fervor, but once back in his palace, the opulence resumed. Since Siamese princes were obligated to have as many children as possible to ensure loyal servants to the throne, he soon had a harem, and by the time he was twenty, Mongkut had sired two children and had several wives and concubines.

At that point, the prince began a second scheduled stint in the monastery, but after only two weeks, his father the king unexpectedly died. To the peoples surprise, the council of princes and nobles, which had the last say in succession to the throne, bypassed Mongkut in favor of his much older half-brother, Jessadabodindra, whose mother had not been a queen but a concubine. But as the kings oldest son, he had been handling foreign affairs and was considered better prepared for the many problems facing Siam. Jessadabodindra took the throne as Rama III .

Prudently, Mongkut announced that he would remain a monk. The new king was well aware that the people favored Mongkut, and he could easily have silenced his potential rival. Only a few years before, a new king in neighboring Burma had marked his coronation by having all his brothers and cousins killed. (No commoners were allowed to touch a royal person, but the Burmese king got around that inconvenience by having them placed in crimson velvet sacks and beaten to death with clubs.) In Bangkok, Rama III was pleased with Mongkuts shrewd decision to forestall any conflict, and a wary truce between the half-brothers prevailed.

A Monks Progress

The royal prince took up the austere life of the monastery, complete with the begging bowl and absolute obedience to the 227 rules of conduct. They included daily fasting from noon until dawn and a chastity so strict that he was not permitted even to make eye contact with a woman. He was known as Makuto Bikkhu (the Pali words for Mongkut the beggar). Within the monastery, titles and rank were irrelevant; abbot and monks alike made their daily treks with their begging bowls; only years of good conduct and superior knowledge would bring precedence in the order. With characteristic tenacity and intelligence, Makuto Bikkhu set out to deserve it. He endeavored to study ancient texts, understand and follow the precepts of Gautama Buddha , and sift out what he saw as the impurities that had crept into the doctrine over the centuries.

But the more he tried, the less Mongkut was happy with the state of his Buddhist order. Many of the monks were practicing the rituals mechanically, without real understanding. Some were primarily interested not in liberating themselves from the cycle of rebirth, as Buddha had urged, but in gaining the supernatural powers, such as levitation, that the founder considered incidental to mastering meditation. Over the years, the rational purity of Buddhism had been contaminated by superstitions and doctrines taken from Hinduism and animism . Even worse, the teachers entrusted with preaching the doctrine didnt really understand it. When Mongkut asked for clarification, they would shout angrily, The Great Ones have always done this!

Mongkut was on the verge of turning in his robe when he found a Burmese monk of the ancient Mon race , who understood and practiced the doctrine in a pure form. From his new teacher, Mongkut learned the precepts he craved along with a new understanding of meditation and the quest for liberation. After three years, he did so well in the examinations in the sacred Pali tongue that he was promoted to head of the examining board. He founded his own school of Pali studies and became famed as a teacher, gathering both monks and laymen as disciples in his mission to reform the faith.

During these years, the royal monk made pilgrimages to cities and towns far from Bangkok, including the ancient ruins of Sukhothai, where he found relics of Siams first king, Ram Kamheng. Long before the monarchs had been revered as god-kings, Ram Kamheng had been a benevolent, almost democratic ruler, levying no taxes and treating even his enemies with justice. He kept a bell outside his palace that any subject could ring to summon the king to answer a question or address a complaint. Mongkut took the stone bench that had been Ram Kamhengs throne back to his monastery, where he used it to preach from.

Next page