Table of Contents

Praise For Mugabe*

The best argued and best written indictment yet of the man Nelson Mandela mockingly calls Comrade Bob.

The Economist

Martin Meredith offers a heartfelt look at African politics through the lens of an informed and objective journalist.... It is a book that gives the full story on Zimbabwes current predicament....

Quarterly Black Review of Books

An accessible introduction.

Foreign Affairs

Martin Merediths book is not so much a biography as a brief gallop through the unfolding moral fable of independent Zimbabwe to the present day. As such it is a useful short guide....

The Sunday Times

Fast paced and readable.

The Nation

The book is highly readable, clear, and fast-moving. It is excellent on Mugabes early life and the way he became drawn into the struggle of Zimbabwe. It is also well-timed....

The Financial Times

Concise and lucid.

Wall Street Journal

Pithy, authoritative, and highly readable: journalism of the highest order.

NOAH RICHLER, National Post

Martin Merediths account of the pursuit of power and plunder is especially good on the early years of Mugabe as an African guerilla fighter.

The Telegraph

*Previously published in North America as Our Votes, Our Guns

ALSO BY MARTIN MEREDITH

The Past Is Another Country: RhodesiaUDI to Zimbabwe

The First Dance of Freedom: Black Africa in the Postwar Era

In the Name of Apartheid: South Africa in the Postwar Era

South Africas New Era: The 1994 Election

Nelson Mandela: A Biography

Coming to Terms: South Africas Search for Truth

Elephant Destiny: Biography of an Endangered Species in Africa (published in the UK as Africas Elephant: A Biography

Fischers Choice: A Biography of Bram Fischer

The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence (published in the UK as The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence)

Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British,

the Boers, and the Making of South Africa

(published in the UK as Diamonds, Gold and War:

The Making of South Africa

Our votes must go together with our guns. After all, any vote we shall have, shall have been the product of the gun. The gun which produces the vote should remain its security officerits guarantor. The peoples votes and the peoples guns are always inseparable twins.

ROBERT MUGABE, 1976

[1]

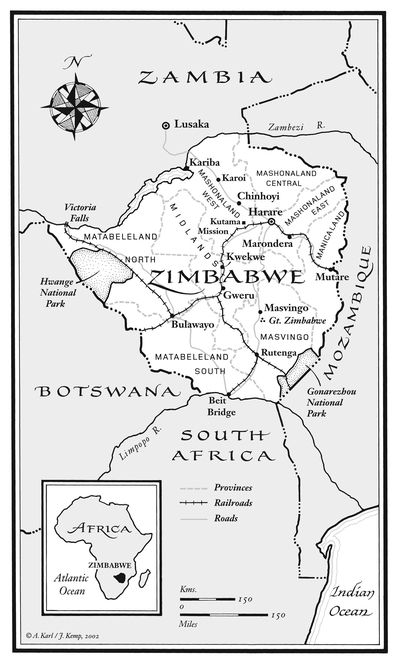

THE PRIEST AND THE PRESIDENT

FROM THE WINDOW of his book-lined study, Father Dieter Scholz gazed out at the hills surrounding Chishawasha Mission as he reflected on the character and career of Robert Mugabe, the aging president of Zimbabwe. They had first met at a secret gathering in Salisbury in December 1974 a few days after Mugabe had been released from eleven years imprisonment during a cease-fire in the guerrilla war against white rule in Rhodesia, as Zimbabwe was then called. Father Scholz, a Jesuit, had been one of the few white priests to support the African nationalist cause. As a member of the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission, he had played a leading role in investigating wartime atrocities by the Rhodesian security forces. Together with a small band of Catholic colleagues, he was regarded by Ian Smiths regime as an enemy of the state. Smith had seized independence from Britain in 1965, determined to halt the tide of black nationalism sweeping through Africa that had led Britain to hand over its other colonies to African rulers. In the civil war that subsequently broke out in Rhodesia in 1972, Smith acted ruthlessly against his opponents, both black and white. Father Scholz was kept under constant surveillance. With a new cease-fire in place, he and his colleagues had gone to the meeting with Mugabe, in a college building in the city centre, to gain a first-hand account of the negotiations that had led to Mugabes release. He was quiet spoken and articulate, recalled Father Scholz in 2001. There was no rancour.

Mugabe told the gathering that during the previous month in Que Que prison he had been in the process of writing a Latin examination for a law degree when an African envoy arrived asking him and other senior members of the banned Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) to attend a summit meeting of African leaders in neighbouring Zambia that was intended to pave the way to negotiations for a Rhodesian settlement. He was told the plan was backed by Tanzanias Julius Nyerere, Zambias Kenneth Kaunda, Mozambiques Samora Machel, and Botswanas Seretse Khama, all of whom had hitherto supported the war effort, allowing guerrillas to use their territories to establish rear bases and supply lines. Also involved in the plan was the South African prime minister, John Vorster, who had provided the Rhodesian security forces with crucial support and who was prepared to lean heavily on Smith to get him to cooperate. As part of the plan, Mugabe was told, the Rhodesian authorities had agreed to his temporary release from prison; a senior white official subsequently visited him to promise that the government would pay for any costs resulting from an interruption to his law examinations.

But Mugabe was hostile to any idea of negotiations. His years of imprisonment had only hardened his resolve to pursue revolution in Rhodesia. Alone among the nationalist leaders, he saw no reason to seek a compromise with Rhodesias white rulers that would leave the structure of white society largely intact and thwart his hopes of achieving an egalitarian peoples state. Whereas other imprisoned nationalists, such as his main rival, Joshua Nkomo, the leader of the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (Zapu), were willing to come to terms with Ian Smith, Mugabe regarded armed struggle as an essential part of the process of establishing a new society.

Mugabes first reaction to the proposal to attend the summit meeting in Lusaka was to turn it down. We Zanu leaders felt that we could not entertain talks at this stage, that it was too early, he told the Catholic group. Even when the African envoy returned to Que Que prison two days later with a written invitation signed by Nyerere, Kaunda, Machel, and Khama, Mugabe was still reluctant to go. We were very angry because we thought that the heads of state were selling us out, he explained. Only under duress had he finally agreed to travel to Zambia for a preliminary meeting. The four heads of state said we could prosecute the war to the end, but if we had a chance to achieve the same aim without bloodshed, we should do so. They also wanted Zanu and Zapu to bury their differences and form a united front for the negotiations. But Mugabe remained recalcitrant. Soon afterwards he returned to his prison cell.

When the summit meeting eventually took place in Lusaka, Zambia, in December 1974, it was a fractious event. The African presidents were infuriated by the continuing divisions between Zanu and Zapu. Nyerere attacked both Zanu and Zapu, Mugabe reported. He scolded us and then Kaunda spoke and attacked us still more viciously, calling us treacherous, criminal, selfish and not taking the interests of our people to heart. If we did not comply, he would no longer entertain our military presence in Zambia. Machel, he said, had made similar threats about Mozambiques support.