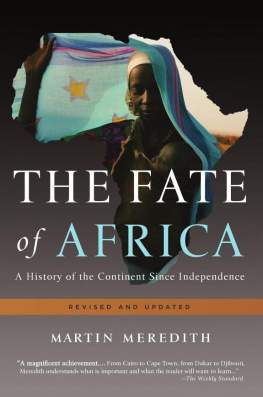

Further praise for The State of Africa:

The value of Merediths towering history of modern Africa rests not so much in its incisive analysis, or its original insights; it is the sheer readability of the project, combined with a notable lack of pedantry, that makes it one of the decades most important works on Africa. Spanning the entire continent, and covering the major upheavals more or less chronologically from the promising era of independence to the most recent spate of infamies (Rwanda, Darfur, Zimbabwe, Liberia, Sierra Leone) Meredith brings us on a journey that is as illuminating as it is gruelling... Nowhere is Meredith more effective than when he gives free rein to his biographers instincts, carefully building up the heroic foundations of national monuments like Nasser, Nkrumah, and Haile Selassie only to thoroughly demolish those selfsame mythical edifices in later chapters. In an early chapter dealing with Biafra and the Nigerian civil war, Meredith paints a truly horrifying picture, where opportunities are invariably squandered, and ethnically motivated killings and predatory opportunism combine to create an infernal downward spiral of suffering and mayhem (which Western intervention only serves to aggravate). His point is simply that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely which is why the rare exceptions to that rule (Senghor and Mandela chief among them) are all the more remarkable. Whether or not his pessimism about the continents future is fully warranted, Merediths history provides a gripping digest of the endemic woes confronting the cradle of humanity

Publishers Weekly

A clear-sighted examination of Africas plight... It is true, as Meredith says, that fifty years after the start of Africas independence, the prospects seem bleaker than ever before. He is right, too, in asserting that Africa has suffered grievously from its Big Men and the ruling elites preoccupation with holding power for self-enrichment. Contrary to the simplistic view of those who prefer to lash the West for its mishandling of the continent, there is a vast amount only Africa can put right

W. F. D EEDES , Daily Telegraph

Any would-be demonstrator at the G8 summit in Scotland this week should take a look at this harrowing but sober volume. Martin Meredith offers an excellent account of the miseries of modern Africa, relentless in its scope and distressing in its intensity. He gives in his more discursive sections a withering critique of the futility and hypocrisy of Western governments in a continent they have made only darker

Sunday Mail (Scotland)

The State of Africa is a heavy book, but it is light reading because it is so unfashionably straightforward. Martin Meredith has written a narrative history of modern Africa, devoid of pseudo-intellectual frills, gender discourse or post-colonial angst. He takes each of the larger African countries and tells you what happened there after independence. In chronological order. It is a joy. Africas rulers will hate it... Some of these strongmen were monsters. Meredith recounts their careers plainly and dispassionately... Dramatic as these tyrants tales may be, they are less revealing than Merediths sober demolition of some of Africas heroes... Merediths book so convincingly shows [that] it is bad leadership, first and foremost, that has held the continent back

Wall Street Journal

First published in Great Britain by The Free Press, 2005

An imprint of Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

This edition published by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2011

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright Martin Meredith, 2005, 2006, 2011

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

The right of Martin Meredith to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

PICTURE CREDITS

,

, Getty Images

, Corbis

, Popperfoto

Magnum Photos

Associated Press

Camera Press

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-85270-387-8

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85720-389-2

Typeset by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

CONTENTS

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi Out of Africa always something new

Pliny the Elder

AUTHORS NOTE

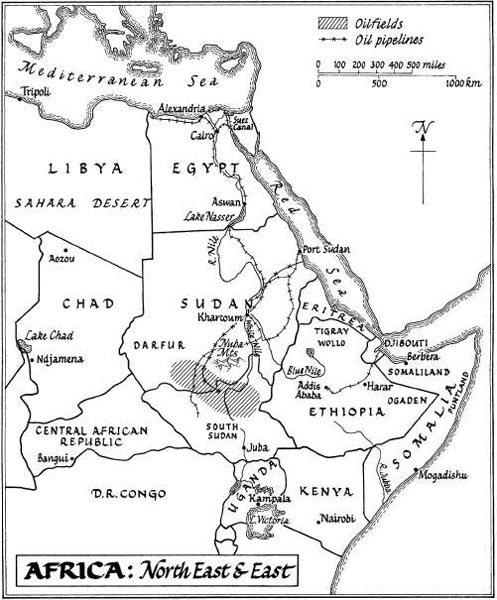

I n 1964, at the age of twenty-one, I set out from Cairo travelling up the Nile on a journey to central Africa. In many ways, my African journey has continued ever since. As a young reporter on the Times of Zambia, I was fortunate enough to witness the surge of energy and enthusiasm that accompanied independence. As a foreign correspondent based in Africa for fifteen years, my experience was more often related to wars, revolution and upheaval. As a research fellow at St Antonys College, Oxford, and as an independent author, I sought deeper perspectives on modern Africa. Along the way I have met with much generosity and goodwill. Many people on many occasions have given me valued help and assistance. To list them here would cover too many pages. But for the innumerable acts of kindness, of hospitality and of friendship I have received, I am profoundly grateful. What has always impressed me over the years is the resilience and humour with which ordinary Africans confront their many adversities. This book is intended as testimony to their fortitude.

INTRODUCTION

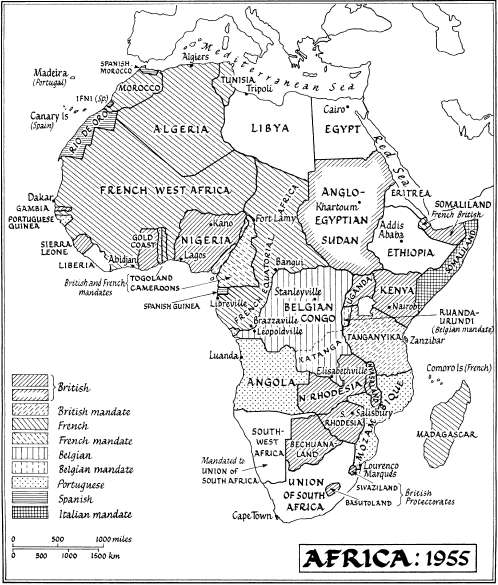

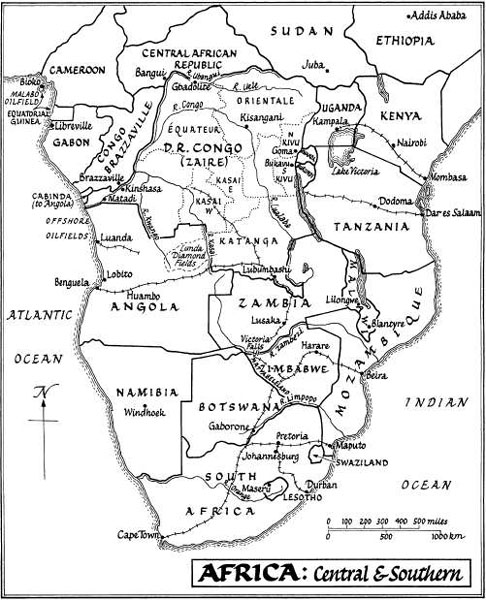

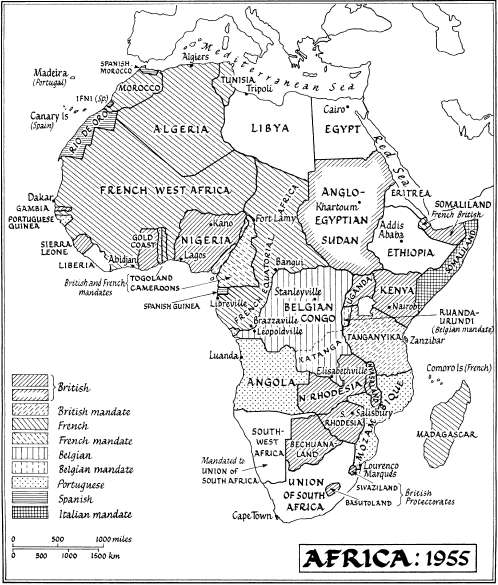

D uring the Scramble for Africa at the end of the nineteenth century, European powers staked claims to virtually the entire continent. At meetings in Berlin, Paris, London and other capitals, European statesmen and diplomats bargained over the separate spheres of interest they intended to establish there. Their knowledge of the vast African hinterland was slight. Hitherto Europeans had known Africa more as a coastline than a continent; their presence had been confined mainly to small, isolated enclaves on the coast used for trading purposes; only in Algeria and in southern Africa had more substantial European settlement taken root.

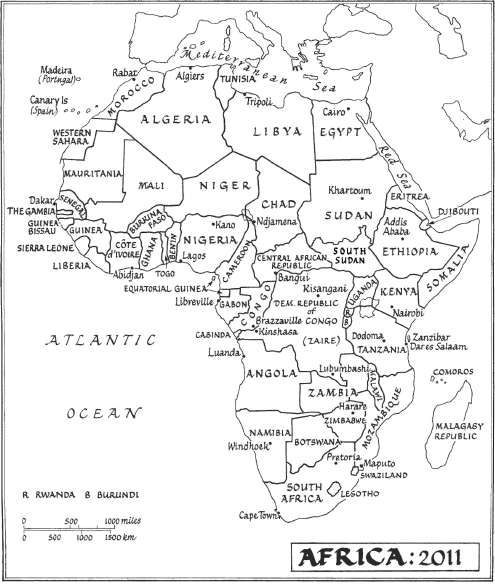

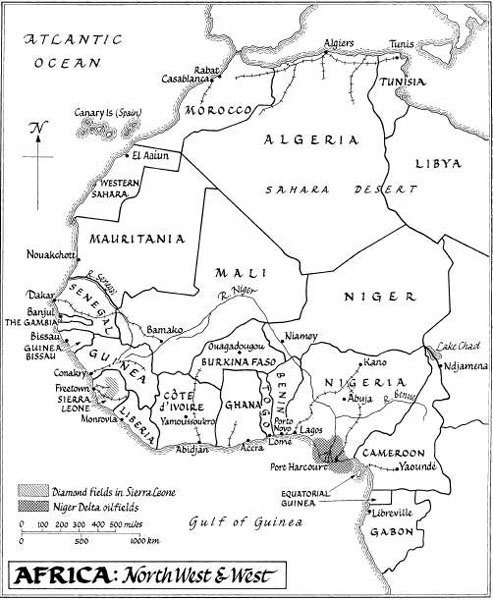

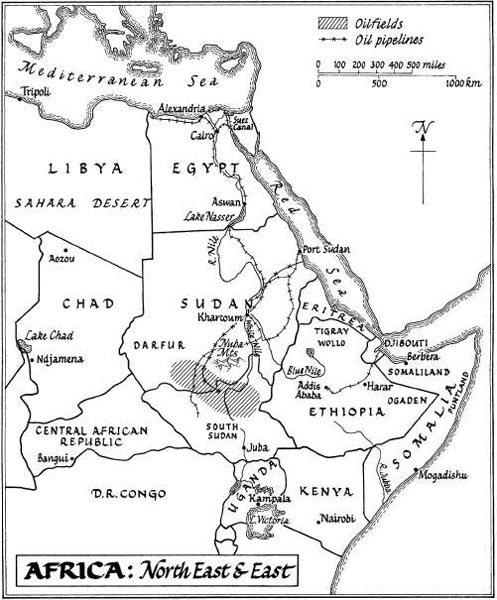

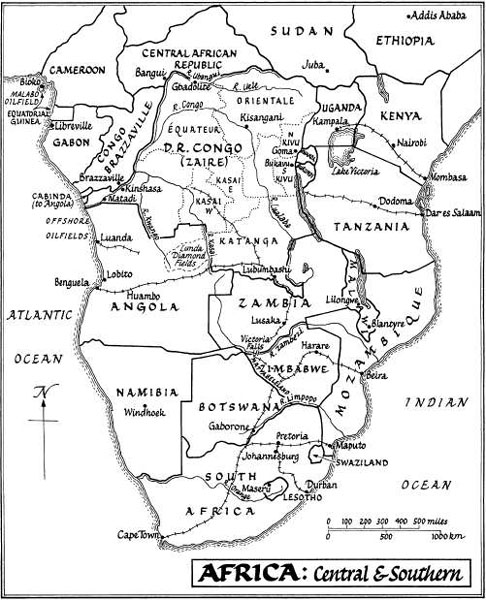

The maps used to carve up the African continent were mostly inaccurate; large areas were described as terra incognita. When marking out the boundaries of their new territories, European negotiators frequently resorted to drawing straight lines on the map, taking little or no account of the myriad of traditional monarchies, chiefdoms and other African societies that existed on the ground. Nearly one half of the new frontiers imposed on Africa were geometric lines, lines of latitude and longitude, other straight lines or arcs of circles. In some cases, African societies were rent apart: the Bakongo were partitioned between French Congo, Belgian Congo and Portuguese Angola; Somaliland was carved up between Britain, Italy and France. In all, the new boundaries cut through some 190 culture groups. In other cases, Europes new colonial territories enclosed hundreds of diverse and independent groups, with no common history, culture, language or religion. Nigeria, for example, contained as many as 250 ethnolinguistic groups. Officials sent to the Belgian Congo eventually identified six thousand chiefdoms there. Some kingdoms survived intact: the French retained the monarchy in Morocco and in Tunisia; the British ruled Egypt in the name of a dynasty of foreign monarchs founded in 1811 by an Albanian mercenary serving in the Turkish army. Other kingdoms, such as Asante in the Gold Coast (Ghana) and Loziland in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) were merged into larger colonial units. Kingdoms that had been historically antagonistic to one another, such as Buganda and Bunyoro in Uganda, were linked into the same colony. In the Sahel, new territories were established across the great divide between the desert regions of the Sahara and the belt of tropical forests to the south Sudan, Chad and Nigeria throwing together Muslim and non-Muslim peoples in latent hostility.

Next page