THE FORTUNES OF

AFRICA

Martin Meredith is a journalist, biographer, and historian who has written extensively on Africa and its recent history. His previous books include Mandela; Mugabe; Diamonds, Gold, and War; Born in Africa; and The Fate of Africa. He lives near Oxford, England.

Copyright 2014 by Martin Meredith.

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2014

A CBS COMPANY

Published in 2014 in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

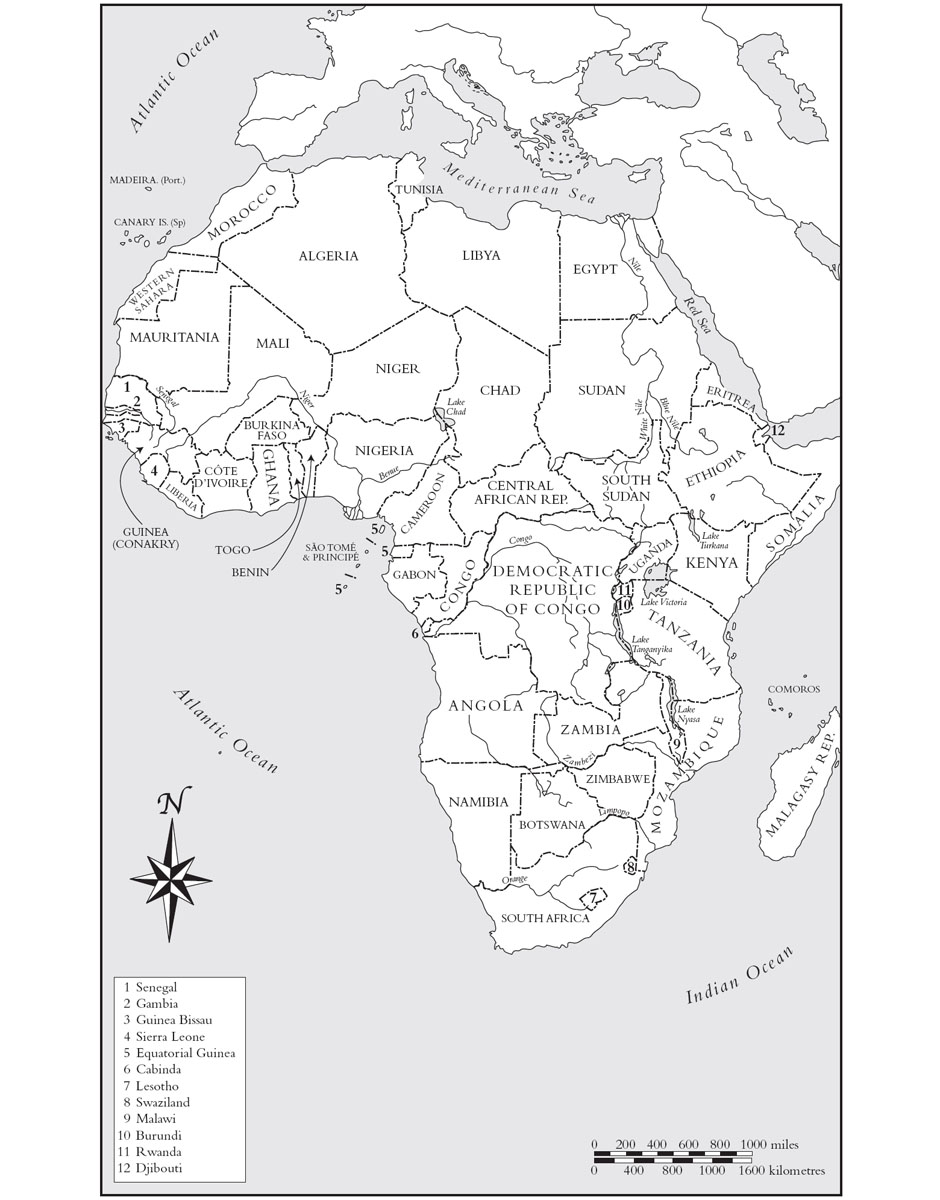

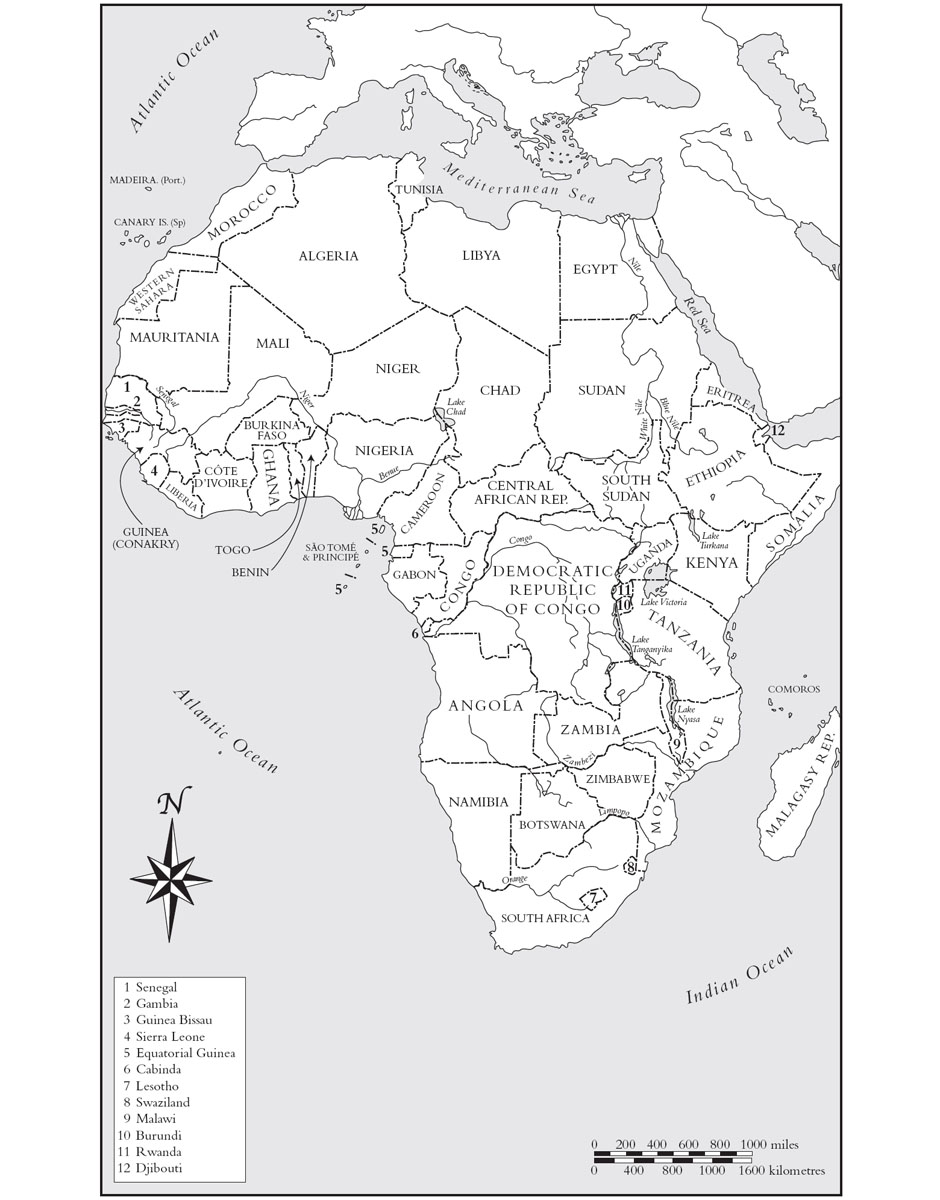

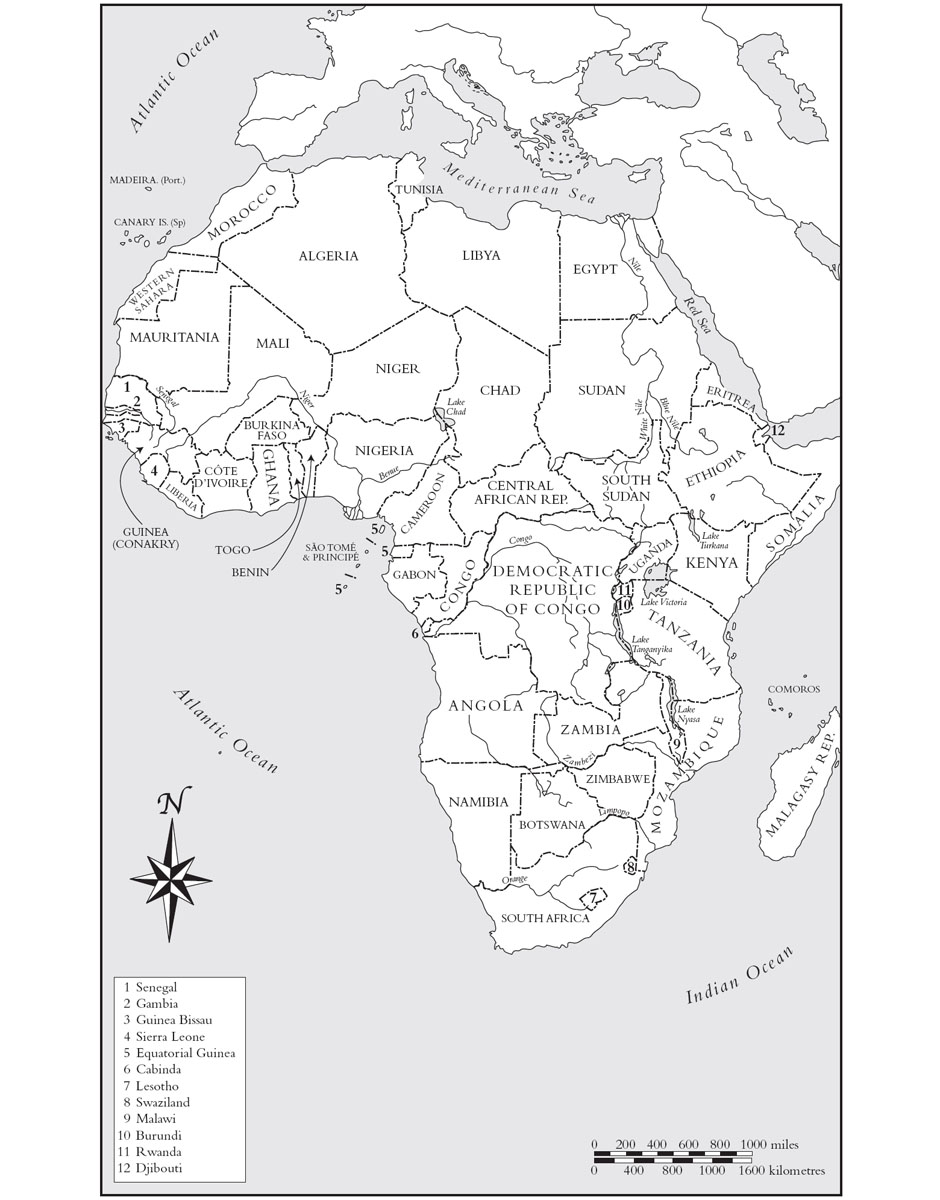

Maps by ML Design

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014939816

ISBN 978-1-61039-460-4 (EB)

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

E ver since the era of the pharaohs, Africa has been coveted for its riches. The pyramids of the Nile Valley dazzled the rest of the world not just because of the ingenuity of their architects and builders but as symbols of the wealth of Egypts rulers who commissioned them as stepping stones to the afterlife.

Legends about Africas riches endured for millennia, drawing in explorers and conquerors from afar. Stories in the Bible about the fabulous gifts of gold and precious stones that the Queen of Sheba brought King Solomon during her visit to Jerusalem in the tenth century BCE grew into folklore about the land of Ophir that inspired European adventurers in their quest for gold to launch a war of conquest in southern Africa 3,000 years later.

Land was another prize. The Romans relied on their colonies in north Africa for vital grain shipments to feed the burgeoning population of Rome; they named one of their coastal provinces Africa after a Berber tribe known as the Afri who lived in the region of modern Tunisia. Arab invaders followed in the wake of the Romans, the first wave arriving in the seventh century, eventually supplanting indigenous chiefdoms across most of north Africa; they used the Arabic name Ifriqiya to cover the same coastal region.

When European mariners began their exploration of the Atlantic coastline of Africa in the fifteenth century, they applied the name to encompass the whole continent. Their aim initially was to find a sea route to the goldfields of west Africa which they had learned was the location from where camel caravans carrying gold set out to cross the Sahara desert to reach commercial ports on Africas Mediterranean coast. Their interest in the west African goldfields had been stimulated as the result of a visit that the ruler of the Mali empire, Mansa Musa, paid to Cairo in 1324 while making a pilgrimage to Mecca. He was so generous in distributing gold that he ruined the money markets there for more than ten years. European cartographers duly took note. A picture of Mansa Musa decorates the Catalan Atlas of 1375, one of the first sets of European maps to provide valid information about Africa. A caption on the map reads: So abundant is the gold that is found in his country that he is the richest and most noble king in all the land. Modern estimates suggest that Mansa Musa was the richest man the world has ever seen, richer even than todays billionaires.

Another commodity in high demand from Africa was slaves. Slavery was a common feature in many African societies. Slaves were often war-captives, acquired by African leaders as they sought to build fiefdoms and empires and used as labourers and soldiers. But the long-distance trade in slaves, lasting for more than a thousand years, added a fearful new dimension. From the ninth century onwards, slaves from black Africa were regularly marched across the Sahara desert, shipped over the Red Sea and taken from the east coast region and sold into markets in the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Arabian peninsula and the Persian Gulf. In the sixteenth century, European merchants initiated the trans-Atlantic trade to the Americas. Most of the inland trade in slaves for sale abroad was handled by African traders and warlords. Fortunes were made at both ends of the trade. By the end of the nineteenth century, the traffic in African slaves amounted in all to about 24 million men, women and children.

Africa was also valued as the worlds main supplier of ivory. For centuries, the principal demand for Africas ivory came from Asia, from markets in India and China. But in the nineteenth century, as the industrial revolution in Europe and North America gathered momentum, the use of ivory for piano keys, billiard balls, scientific instruments and a vast range of household items made it one of the most profitable commodities on earth.

A greedy and devious European monarch, Leopold II of Belgium, set out to amass a personal fortune from ivory, declaring himself King-Sovereign of a million square miles of the Congo Basin. When profits from the ivory trade began to dwindle, Leopold turned to another commodity wild rubber to make his money. Several million Africans died as a result of the rubber regime that Leopold enforced, but Leopold himself succeeded in becoming one of the richest men in the world.

In turn, Leopolds ambition to acquire what he called a slice of this magnifique gteau africain was largely responsible for igniting the scramble for African territory among European powers at the end of the nineteenth century. Hitherto, European activity in Africa had been confined mainly to small, isolated enclaves on the coast used for trading purposes. Only along the Mediterranean coast of Algeria and at the foot of southern Africa had European settlement taken root. But now Africa became the target of fierce European competition.

In the space of twenty years, mainly in the hope of gaining economic benefit and for reasons of national prestige, European powers claimed possession of virtually the entire continent. Europes occupation precipitated wars of resistance in almost every part of the continent. Scores of African rulers who opposed colonial rule died in battle or were executed or sent into exile after defeat. In the concluding act of partition, Britain, at the height of its imperial power, provoked a war with two Boer republics in southern Africa, determined to get its hands on the richest goldfield ever discovered, leaving a legacy of bitterness and hatred among Afrikaners that lasted for generations.

By the end of the scramble, European powers had merged some 10,000 African polities into just forty colonies. The new territories were almost all artificial entities, with boundaries that paid scant attention to the myriad of monarchies, chiefdoms and other societies on the ground. Most encompassed scores of diverse groups that shared no common history, culture, language or religion. Some were formed across the great divide between the desert regions of the Sahara and the belt of tropical forests to the south, throwing together Muslim and non-Muslim peoples in latent hostility. But all endured to form the basis of the modern states of Africa.

Next page