Thank you for buying this ebook, published by HachetteDigital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about ourlatest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

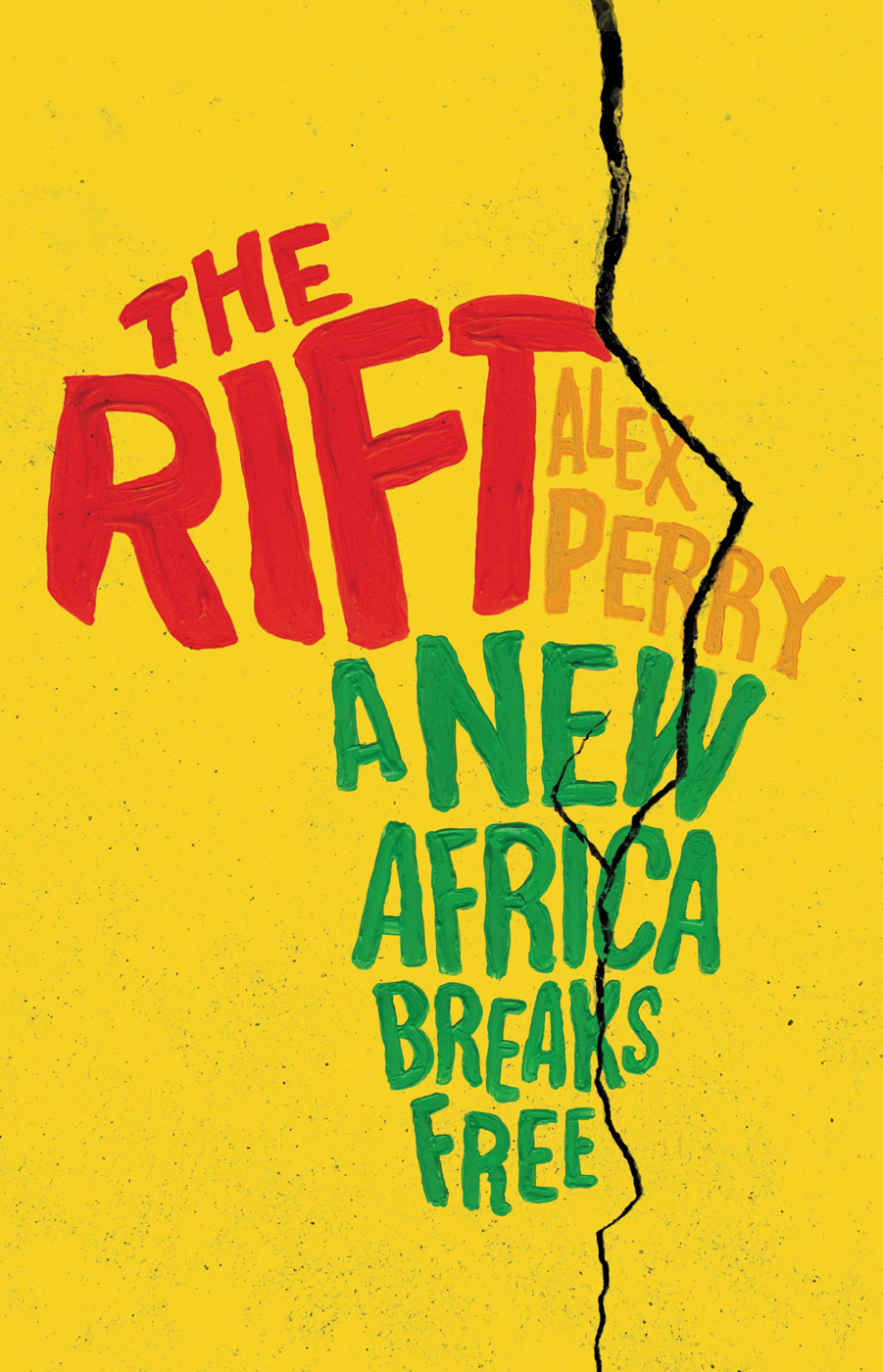

Copyright 2015 by Alex Perry

Cover art and design by Rawshock Design

Author photograph by burlisonphotography.co.uk

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: November 2015

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Photographs by Dominic Nahr

ISBN 978-0-316-33379-5

E3

Lifeblood

Falling Off the Edge

For Dominic Nahr, who always had a different angle And for Tess, always

For a European to write a book about Africa and freedom is an undertaking of precarious legitimacy. Europeans have a long history of exploiting Africans, and of getting Africa wrong. I have tried to avoid the latter but there is no doubt I am guilty of the former. A perfect stranger, I asked hundreds of Africans to entrust me with their stories without pay or other compensation, often in a detail that was indecent and at huge risk to themselves. These are not my stories, I borrowed them, even stole them, and I owe a deep debt to their true owners.

My highest ambition is that I have done them justice. Thats also a reason why you wont find many old Africa hands in these pages. Foreign academics and journalists tend to define Africa to the outside world by referencing or quoting other foreignersaid workers or other academics. It is this presumptuous and incestuous process that has led to so many false conclusions. Even when foreigners alight on truth, too often speaking up for Africa has become speaking for it, and defending Africas interests has become deciding them. While this book contains some conclusions of my own, they are a reporters inferences, drawn from what Africans showed and told me. I wanted Africans to show and tell you their stories too, so you would hear what I heard and see what I saw, and that has required giving them space to do so.

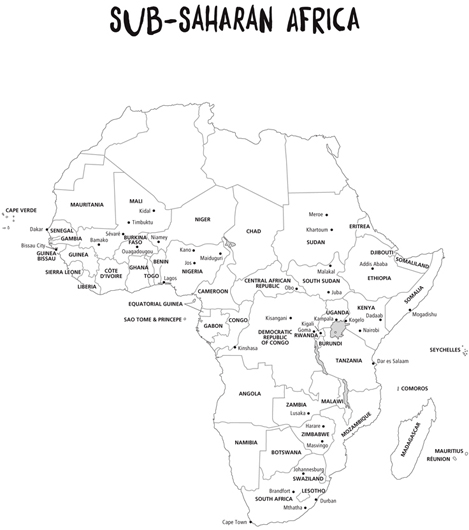

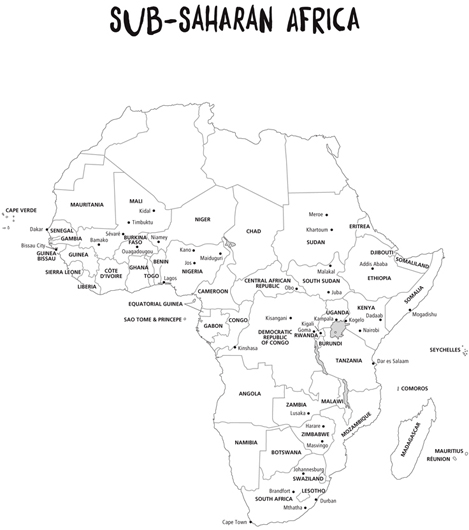

But already Im in danger of making the kind of generalizations that cause Africans to wince. Africa is the biggest and most diverse continent on earth and to speak of it or its people as a monolith is a grand folly. After all, we split the non-African half of the worlds super-continent into three: Europe, the Middle East and Asia. I have drawn my own line across the Sahara, which remains such a barrier to culture, language, politics and economics that it is better to think of North AfricaMorocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Egyptas part of Arabia and Africa as the 49 countries to the south. Below the Sahara, the variation is still immense. I have tried to respect that by treating each country, and sometimes parts of them, as distinct. However my contention is that the nations and peoples of this vast land share some common themes. Many have a mutual history, most recently in colonialism and liberation, but before that in the experience of living in an endless and empty continent. That collective context means that the stories of one can hold true for many others and why, I think, we can speak meaningfully about Africans and Africa.

But heres the thing: not many of us. Given the dimensions of the place, most people in Africa, local or foreign, sensibly limit themselves to a corner or two. Even in my profession, almost no one attempts to cover the entire continent. The shrinking resources of the particular magazine for which I worked meant that, for close to a decade, that was my job. Thats my best defence for writing this book. Africa is nearing the end of an epic quest for freedom that will revolutionize perceptions of it and change the world. Though I am not African, and though I was traversing the breadth of the continent merely because of the declining fortunes of a far-off employer, I turned out to be one of the few who could tell the whole story.

At the heart of Africa lie the Virungas, a chain of volcanoes that are home to the last of the mountain gorillas. Every few years one of the craters erupts, sending thick rivers of lava rolling down its steep slopes, sweeping away the misty bamboo thickets where the gorillas live, smashing through villages and burying farms. These local disasters are dwarfed by the continental cataclysm to come. The Virungas are fiery peepholes into a tectonic fissurethe Great Riftthat will one day rend Africa in two from Eritrea down to Mozambique. Seen from 3,000 metres up under a craters lip, the distinct characters of these two future Africas are already apparent. To the west, spreading lazily down to the Atlantic, are a thousand kilometres of Congolese jungle, the canopy rolled flat by low, lumbering rain clouds. To the east is the high and rocky East African savannah, cool, grassy, blessedly free of mosquitoes and running clear over several horizons before plunging into the Indian Ocean.

A continental split happens in two stages. First, as the earths plates move apart, they stretch the lands surface so thin that the earths molten core bursts through and settles in monstrous pustules of cooling rock and ash. Later, as the partition widens further, the cones collapse and form a depression that, when the last one falls, fills with angry, hissing sea. From a distance, the division can seem to proceed peacefully. Africas Rift is widening at the speed a fingernail grows and a process that began 100 million years ago will take at least another 10 million to complete. Up close, however, the separation can be violent. In 2002, the largest Virunga, Mount Nyiragongo, spat a stream of lava 300 metres wide into the middle of Congos second city, Goma, carving the place in two and asphyxiating or incinerating 147 people. Three years later and several hundred kilometres to the north-west, a group of Ethiopian villagers watched helplessly as a crack six metres wide and 58 kilometres long opened up in the earth beneath their feet, swallowing huts, small hills and a herd of bellowing camels.