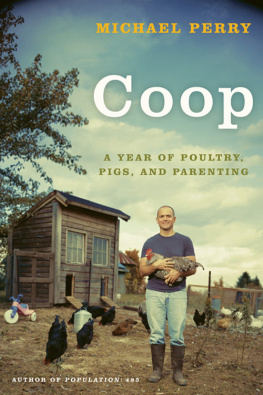

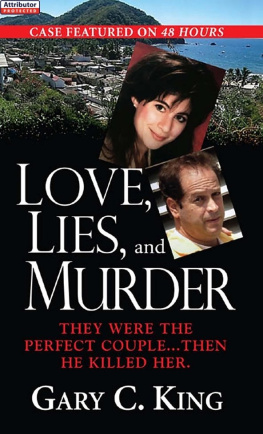

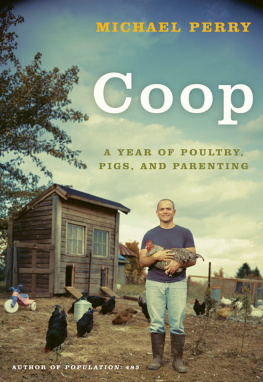

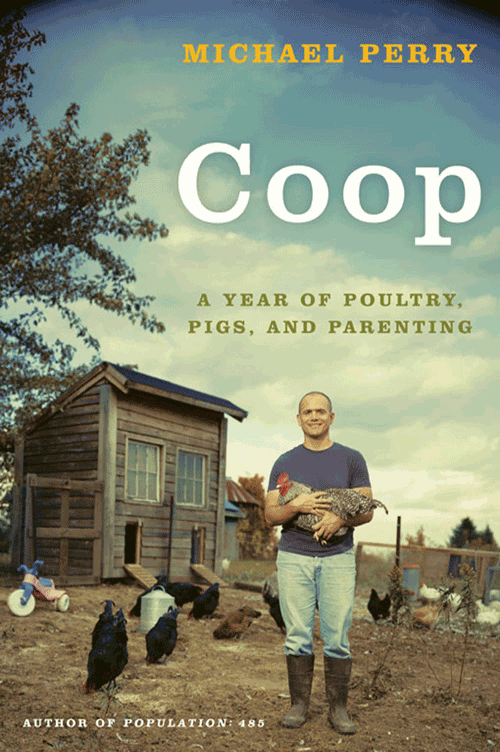

Michael Perry

Coop

A Year of Poultry, Pigs, and Parenting

For the tiny pilot

Contents

At the earliest edges of my memory, my father is

This morning while splitting wood, I attempted to clear my

I am building a glorious chicken coop in my mind.

I am in the office working after supper when Anneliese

Winter is on the fizzle, and Mister Big Shot is

Across the valley, the bare-bone tree line is thickening. The

Today a dog bit me grievously upon the ass. I

My daughter is weeping in the timothy. She is a

At some point every Sunday evening of my childhood there

One summer evening when the other kids got to go

Sunday mornings when I was a boy I worshipped the

Before our family grew large, my brother John and I

Recently I had an apparently deep thought. I scribbled it down quickly so that it might not escape the loosely woven sieve that is my brain. I then spent untold hours polishing the scribble until it was an aphoristic gem of original profundity. Shortly after that, I revisited an essay I had written seven years previous only to find the exact same observation, typed nearly word for word. I have reached that point in my life where every other thing I say is something Ive said before. For instance, I regularly catch myself trying to describe the scent of dirt. I am repetitively waylaid by my affection for particular words. (The modifier little pops up like Whac-A-Mole in my rough drafts and is never completely eradicated.) Further amplifying the echo, bits and pieces of this book were worked out in shorter, previously published pieces some readers may recognize. I like to imagine this reflects the development of a certain literary style when in fact it is more likely I am developing certain nervous tics. To say nothing of engaging in a freelance writers favorite sport: recycling .

When Im not repeating myself, Im contradicting myself. For instance, in the book Truck: A Love Story I stated that my father never allowed us to have toy guns; lately I recall we were allowed to keep a pair of realistic-looking squirt guns given to us by a relative. I once wrote of a cow called Angie only to find out her real name was Aggie. (Other mistakes of bovine nomenclature have likely been madeI tell you this because the cows cannot speak for themselves.) The ten-day Wisconsin deer hunting season is only nine days long, no matter what I wrote in my most recent hardcover. Sometimes readers point out these contradictions. If they are offered in collegial spirit (we are in this together) I am nearly always happy to post them on my Web site as evidence that my head and feet are a matching set of clay.

Finally, since I believe the term nonfiction depends above all on a readers trust, I must disclose a few intentional partialities. I often change names to give friends and neighbors a veneer of privacy. I use the term recently with some latitude, and for the sake of forward motion I reference the lambing season of 2006 in the context of 2007. Finally, when I write of the church of my childhood, I do so knowing that some will object to the portrayal as either too critical or too benign, and all will find it incomplete, especially when the sect is small and history is spare.

I am grateful for anyone who reads my writing, evenor especiallywith a critical eye, and one phrase never suffers from repetition: Thank you, reader.

At the earliest edges of my memory, my father is plowing, and I am running behind him. I see my feet, going pat-pat-pat over the soil, I see my father, left hand on the wheel, right forearm braced against the fender, head turning back to check the depth of the plow, then forward to gauge his progress. The soil is red and sandy in the high spots and dark and loamy in the low spots, where it curls from the plowshares like strips of licorice, leaving me this square, shin-deep trough in which to travel. I trail the sound of the little tractor, so close to ground I can hear the soft plop of the overturned clods. Now and then the plow slices the soil so cleanly that a chubby white grub drops into the furrow, unscathed. The grubs are translucent white, their black guts dimly visible, as if through rice paper. Grackles and cow-birds flock the plow, pecking through the new-turned dirt. The grub will not last long. There is my father on his underpowered Ford Ferguson, and there is me trotting right behind him, and there is God above, looking down as I run the straight groove of the furrow, my life laid out on a line drawn in the earth.

In the company of our six-year-old daughter Amy, my wife Anneliese and I have recently moved to a farm. I would like to present some sort of grand agrarian charter, but the whole deal is predicated mainly on the idea of having chickens. We are not alone in this: These Troubled Times seem to have precipitated a fowl renaissance. Mail carriers labor under a groaning load of multicolored hatchery catalogs, the latest issue of Backyard Poultry , and perforated containers that peep. Drop the term chicken tractor in mixed company and behold the knowing nods. The online world is alive with Subaru-driving National Public Radio supporters trading tips on eco-friendly coop construction and the pros and cons of laying mash; my NASCAR-loving brother-in-law tenderly minds a box of chicks beneath a heat lamp in his garage; my biker bar bouncerturnedZen Buddhist pal Billy and his wife the certified nursing assistant are building their second backyard coop with an eye toward expanding into ornamentals. Anecdotal evidence to be sure, and a drop in the Colonels bucket, but something is afoot. The subject of chickens was raised between my wife and me fairly early in our courtship, and has sustained us. We are enthused by the idea of fresh eggs, homegrown coq au vin, and (at least until butchering day) a twenty-four-hour turnaround on the compost. In addition, it is my long-standing opinion that entertainment-wise, chickens beat TV.

Our move is also family-driven. We are assuming responsibility for a farmstead previously owned by my wifes mother. Faced with an unexpected relocation, my mother-in-law wants to keep the place in the family. And in a bit of a flip, we are moving from a northern village to the country in order that my wife might be closer to the university where she sometimes teaches. This will save gas and time, although that glow on the horizon is a mall, and whenever we notice a Prime Commercial sign forty acres nearer, we review our escape plan from a place on which we have yet to pay the property tax.

We are also going rural in the hope that we might become more self-sufficient in terms of firewood, an expanded garden, and perhaps a pair of pigs. Whether through prescience or too much nervous reading, we have developed a low-key doomsday mind-set regarding the imminent future, and believe the time has come to store up some potatoes and teach the younguns how to forage. Amy can already identify a coyote track, and I intend to see to it that she carry the phrase slop the hogs a generation further. To an extent, my wife and I are acting on positive recollections of our own childhoodI was a farm kid from the age of two, and much of my wifes childhood was spent on a farm just one valley over from the spot to which we have moved. But I hope we dont burden Amy with the idea that living outside the city limits is an inherently pious act. That rural equals righteous . As a country kid, I took a while to round the bend on that one, but thanks to a blend of peak oil posts, Kwame Anthony Appiahs Cosmopolitanism , and a week spent buying groceries at a bodega in Bushwick, I am well on my way to reconstructing all residual prejudice. Lets hear it for sensible urbanism. Whenever I catch myself waxing unctuous on the subject of getting back to the land, I think of the Parisian Jim Haynes, who has said city dwellers protect the ecological balance of the countryside by staying away from it. And then there is Ben Logan and his touchstone book The Land Remembers , in which he wrote, All around were reminders that the land was more important than we were. The land could do without us.