For J. & S.

We are in trouble down here. There is blood in the dirt. We have made our call for help. Now we look to the sky.

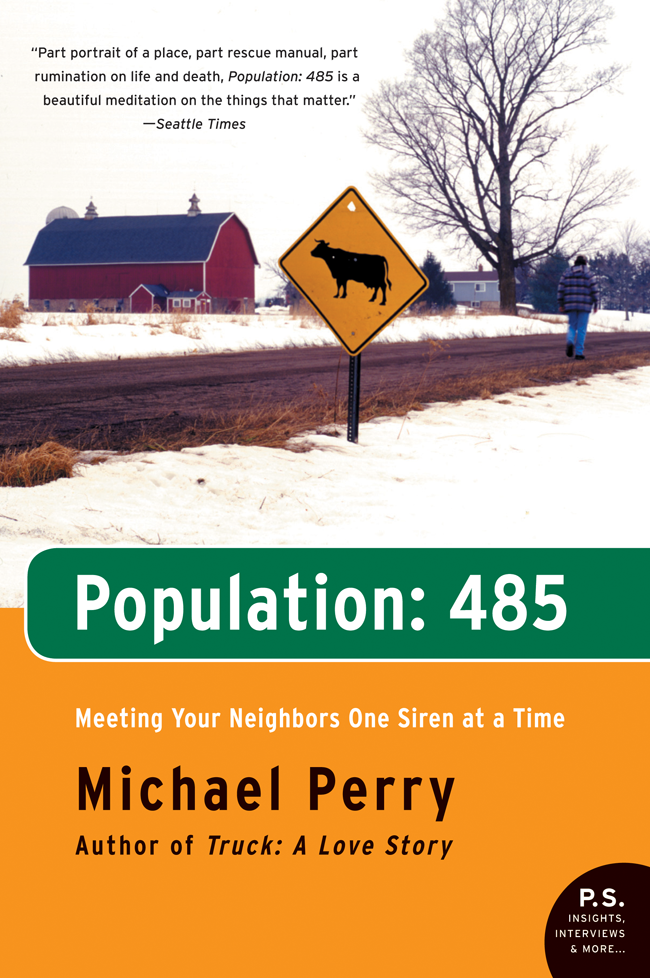

S UMMER HERE COMES ON like a zaftig hippie chick, jazzed on chlorophyll and flinging fistfuls of butterflies to the sun. The swamps grow spongy and pungent. Standing water goes warm and soupy, clotted with frog eggs and twitching with larvae. Along the ditches, heron-legged stalks of canary grass shoot six feet high and unfurl seed plumes. In the fields, the clover pops its blooms and corn trembles for the sky.

If you were approaching from the sky, you would see farmland neatly delineated by tilled squares and irrigated circles. The forests, mostly hardwoods and new-growth pine, butt up against fields, terminating abruptly, squared off at fence lines. The swamps and wetlands, on the other hand, respect no such boundaries, and simply meander the lay of the land, spreading organically in fecund hundred-acre stains. The whole works is done up in an infinite palette of greens.

There is a road below, a slim strip of county two-lane, where the faded blacktop runs east-west, then bendsat Jabowskis Cornerlike an elbow. In the crook of the elbow, right in the space where you would cradle a baby, is a clot of people. My mother is there, and my sister, and several volunteer firefighters, and I have just joined them, and we are all on our knees, kneeling in a ring around a young girl who has been horribly injured in a car wreck. She is crying out, and we are doing what we can, but she feels death pressing at her chest. She tells us this, and we deny it, tell her no, no, help is on the way.

I do my writing in a tiny bedroom overlooking Main Street in the village of New Auburn, Wisconsin. Population: 485. Eleven streets. One four-legged silver water tower. Seasons here are extreme. We complain about the heat and brag about the cold. Summer is for stock cars and softball. Winter is for Friday-night fish fries. And snowmobiles. After a good blizzard, youll hear their Doppler snarl all through the dark, and down at the bar, sleds will outnumber cars. In the surrounding countryside, farmsteads with little red barns have been pretty much kicked in the head, replaced with monster dairies, turkey sheds, and vinyl-sided prefabs. The farmers who came to town to grind feed and grumble in the caf have faded away. The grand old buildings are gone. There is a sense of decline. Or worse, of dormancy in the wake of decline. But we are not dead here. We still have our Friday-night football games. Polka dances. Bowling. If you know who to ask, you can still get yourself some moonshine, although methamphetamine has become the favored homebrew. Every day, the village dogs howl at the train that rumbles through town, and I like to think they are echoing their ancestors, howling at that first train when it stopped here in 1883. Maybe thats all you need to know about this townthe train doesnt stop here anymore.

Mostly I write at night, when most of this wee townexcept for the one-man night shift at the plastics factory, and the most dedicated drinkers, and the mothers with colicky babies, and the odd insomniac widower, and the young couples tossing and turning over charge card balances and home pregnancy testsis asleep. This is my hometown, and in these early hours, when time is gathering itself, I can kill the lights, crack the blinds, and, looking down on Main Street, see the ghost of my teenage self, snake-dancing beneath the streetlight, celebrating some football game twenty years gone. I was a farm boy then, rarely in town for anything other than school activities. I didnt see Main Street unless I was in a parade or on a school bus.

But now Main Street is in my front yard. On a May evening nineteen years ago I walked out of the school gym in a blue gown and left this place. Now I have returned, to a house I remember only from the perspective of a school bus seat. In a place from the past, I am looking for a place in the present. This, as they say, is where my roots are. The trick is in reattaching. About a month after I moved back, I dropped by the monthly meeting of the volunteer fire department.

The New Auburn fire department was formed in 1905. The little village was just thirty years old, but it had already seen its share of change. The sawmill that spawned the settlement ran out of pine trees and shut down before the turn of the century. Forests gave way to farmland and New Auburn became a potato shipping center. Large, hutlike charcoal kilns sprang up beside the rail depot. In time, the village has been home to a wagon wheel factory, a brick factory, and a pickle factory. There was always something coming and going. But then, in 1974, the state converted the two lanes of Highway 53 to four lanes and routed them west of town, and the coming and going pretty much went. We have a gas station, two cafs, a couple of bars, and a handful of small businesses, but the closest thing to industry is the plastics factory, which employs two men per shift, rolling plastic pellets into plastic picnic table covers. Most of the steady work, the good-paying stuff, is thirty or forty miles away. During the day, the streets are still. It is from this shallow pool that the community must skim its firefighters. If we get a fire call during a weekday, we are likely to have more fire trucks than volunteer firefighters to drive them.

During that first meeting, a motion was made and seconded to consider my application as a member. The motion carried on a voice vote, and I was admitted on probationary status. After the meeting concluded, the chief led me to the truck bay. He is a stout man, burly but friendly. By day he dispatches freight trucks. Try on these boots, he said. Weve got a helmet around here somewhere. Someone handed me a stiff pair of old fire pantsbunkers, theyre called. A farmer in a bar jacket showed me how to shift the pumper, his cigarette a sing-along dot dancing from word to word. That was it. I was now a member of the NAAFDthe New Auburn Area Fire Department.

Among my fellow volunteers are a pair of butchers, two truckers, a farmer, a carpenter, a mailman, and a mother of four. A guy like me ends up on the fire department for two reasons: (a) I have a pulse, and (b) I am frequently home during the day. Ive put in seven years now, and am no longer on probation. Ive been to house fires, barn fires, brush fires, and car fires, and Ive had enough training to tell a halligan from a hydrant wrench. When one of the old-timers sends me after a water hammer, I dont take the bait. I have attended firefighting classes at the tech school, where I learned that water hammer is a situation, not a tool. Still, my primary qualifications remain availability and a valid drivers license.

Seven years since the accident, and this is what freezes me, late at night: There was a momenta still, horrible momentwhen the car came squalling to a halt, the violent kinetics spent, and the girl was pinned in silence. One moment gravel is in the air like shrapnel, steel is tumbling, rubber tearing, glass imploding, and thenutter stillness. As if peace is the only answer to destruction. The meadowlark sings, the land drops away south to the hazy tamarack bowl of the Big Swampall around the land is rank with life. The girl is terribly, terribly alone in a beautiful, beautiful world.

As long as I can remember, Stanislaw Jabowski was all stove up. Foggy autumn mornings, the school bus would stop where the county road cut between his house and barn, and wed see him stumping along the path, pails in hand, shoulders rocking side to side with his hitch-along gait. Spare, he was. Short, and lean as a tendon. A walking Joshua tree, with a posture less tribute to adversity overcome than adversity withstood.