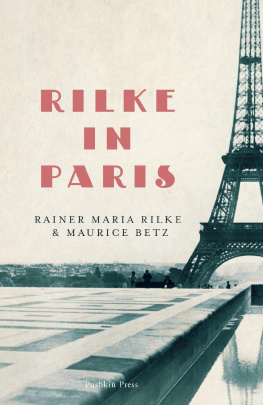

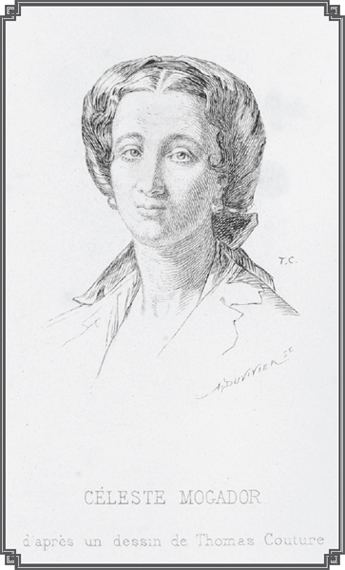

Not quite the Mona Lisa. A portrait of Cleste, age 40, at the peak of her writing career in the 1860s. The life she was leading was etched in her face. The artist has captured her melancholy and quiet determination in this drawing, which frequently accompanied newspaper reviews of her work.

For Frederique Lallement

and

Annette and Peter Dezarnaulds,

two lovers of Paris and Cleste.

Contents

Guide

W hen Cleste Vnard strode into Pariss Caf Anglais in the winter of 184647, heads turned almost in unison to stare at this most celebrated beauty, the City of Lights most sought-after courtesan. The more discerning onlookers searched for imperfections but could find none in this 22-year-old femme fatale. The popinjays at the caf were struck by Clestes sensual face: the large green eyes, her petite nose, full ruby lips and alabaster skin. Her light auburn hair was long and combed back over neat ears so as not to hide any of her exceptional features. Her full figure did not need the corset under the red dress, which only served to accentuate alluring proportions of lush breasts, slim waist and rounded derrire. Clestes long, slim arms, often noted as the most striking of her many physical features, were fully exposed. She undulated just short of a swivel to a table with her friend Frisette, herself eye-catching but a mere shadow in this moment. Cleste removed her bonnet and off-white shawl, then ceremoniously slid off white gloves to expose her slender fingers.

The young men were nervous about approaching her, even though they were among the wealthiest members of Frances aristocracy. Some were afraid because it took courage to accost her, despite the well-accepted fact that women entering the caf were seeking paying paramours. Others knew her reputation for saying Non, Monsieur, merci. They feared her rejection beyond a drink or a meal. Such was Clestes fame that this once low-level prostitute could pick and choose any man with whom she wished to take favours, no matter how wealthy or important; an unusual situation even for the well-known actresses of the era. But then she was more beautiful than Empress Eugnie, Napoleon IIIs Spanish wife; even Queen Victoria, who made a hobby of describing the appearance of notables she met, thought so. It was said that the real princesses of France were the courtesans, who ruled by conquest. Cleste Vnard surpassed these so-called members of royalty. She was more like a queen. She dominated.

The corseted male fops and exhibitionists, with their overly styled hair, tangled cravats, body-hugging trousers and effeminate shoes, stared at the new arrivals but were guarded. Cleste was the unattainable prize, who treated them with neither disdain nor contempt, but who nevertheless rebuffed them with a cold stare or maybe a glance of careless disapproval. Both women knew the onlooking debauched species well enough. These men wanted playthings, not relationships of substance. Their dissolute, privileged lives did not lend themselves to responsibility or work of any kind. Yet Cleste and Frisette remained in search of worthy lovers, who might keep them for a few months, even a year or more in a salubrious apartment. If they met no one suitable, they might at least enjoy a drink, a dinner and banal, flirtatious conversation.

This night it began with something else: abuse. Two degenerate types, knowing they would have no hope of ever dating, let alone bedding Cleste, resorted to obnoxious remarks in an attempt to hurt her, ridiculing her clothes and hair. She returned serve with remarks about their bad teeth and unkempt appearance. This was unexpected. The courtesans were supposed to accept being the butt of this low form of amusement, but not Cleste. She had a tangible power because of her risky, courageous bareback horse riding at the Hippodrome and her fame, which extended back beyond her brave circus acts to her days as Pariss most notable performer at the popular dance halls. She had created her own high-kicking version of the polka, which would later be accepted as the precursor to the cancan. Her outstanding looks and character had made male spectators at the halls, and later the open-air riding circus, fantasise about having her. Her image, active and in repose, inspired myriad artists, poets and writers of the creative period in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as those of the belle poque and beyond. They included composer Georges Bizet, who was driven to operatic genius and fury over her with Carmen. Henri Gervex was motivated by her to deliver sensuality in his painting Rolla; Cleste was the muse for, and in, Thomas Coutures masterful painting Romans During the Decadence; and she rekindled public enthusiasm in Alfred de Mussets poetry. The press reported her every performance, and the occasional dalliance.

Her licence to thrill gave her confidence to stand up to her tormentors. Clestes sharp tongue cut deep.

You mindless slobs have nothing better to do tonight, eh? she goaded. Alone you are cowards. Together you urge each other on without finesse or finery of words. Your champagne-and gin-soaked brains have shrunk to allow you to squeak out attempted cruelties only, which reveal your idiocy. We dont laugh at you. We scorn your unmanliness, which dare I say, would most certainly reach to physical inadequacies!

A dozen dandies at other tables clapped at these remarks.

Who brought this whore to the party? one of her tormentors asked with a vicious glare of defeat. Frisette wanted to leave, but game Cleste refused. At this moment, a dashing, dark-haired man intervened and demanded reparations from the main offender for his unpleasant remarks. Cleste had never seen the man before. There was something intriguing about him. He had none of the effete accoutrements of the dandies, nor their patronising manner which exposed insecurities. He was chivalrous, and clearly an aristocrat. In fact, he was 25-year-old Count Lionel de Chabrillan, the only man who could possibly take Cleste away from her notorious past. Would he be her first true love, and at last help her forget her miserable childhood?

I t was 1832 on a winters late afternoon in Frances industrial southern city of Lyon. Eight-year-old Cleste was coming home in the failing light with her small white dog, Lion. She heard movement behind her. Lion barked a warning but Cleste was no match for the heavy-set brute who grabbed her from behind. She was shocked, but when she realised it was her stepfather, Guy, she punched and kicked and screamed. In her fury, she showed surprising strength as Guy tried to hoist her onto his shoulder. Brave Lion snapped at the mans ankles, and he was kicked hard in the side, causing him to yelp and back off in pain. Guy slapped the little girl across the face and head, subduing her to sobs. He then hurried off with her to a narrow passage in the southern part of the city and a working-class brothel, La Belle du Sud, which, given the shuttered windows, appeared closed at least until night. But Guy, his unshaven face masking several scars from bar-room brawls, knew his way around this place. He pushed through the front door, staggered upstairs past rooms where men were indulging their carnal urges with grunts of pleasure and crude language, and into a large, smoke-filled sitting room and bar. There were five prostitutes with clients playing strip poker. Guy dragged the stunned and frightened Cleste into this scene. Four of the women didnt care about the childs presence. But a fifth, Marianne, saw the fear and shock on Clestes face and protested to Guy, who replied, But shes my daughter! I must hide her from some wild men who would take her from me!