An imprint of Globe Pequot, the trade division of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2022 by Jeff Pearce

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pearce, Jeff, 1963 author.

Title: The Gifts of Africa : how a continent and its people changed the world / Jeff Pearce.

Description: Lanham, MD : Prometheus, an imprint of Globe Pequot, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Past works have reinforced misconceptions about Africa, from its oral traditions and languages to its resistance to colonial powers. Other books have treated African achievements as a parade of honorable mentions and novelties. This book is different-refreshingly different. It tells the stories behind the milestones and provides insights into how great Africans thought, and how they passed along what they learnedProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021029574 (print) | LCCN 2021029575 (ebook) | ISBN 9781633887701 (cloth) | ISBN 9781633887718 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Civilization, WesternAfrican influences. | AfricaCivilization. | AfricaHistory. | AfricaIntellectual life.

Classification: LCC DT14 .P39 2022 (print) | LCC DT14 (ebook) | DDC 960dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029574

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029575

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

To the greatest African I know

IMRU ZELLEKE Witness, Survivor, Ambassador

And this book is offered respectfully to the peoples of Africa, in the sincere hope that I have properly depicted their history and cultures.

Contents

Guide

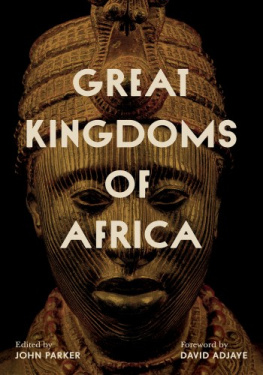

Leo Frobenius had exciting news to share as 1911 got started. On his expedition into the hinterland of Togo, he had visited a shrine outside Ife in what is now modern Nigeria and had found a sculpted head. But it was of such extraordinary beauty that he decided it couldnt have originated from an African mind or have been crafted by black hands. No, this fine specimen, so beautiful and lifelike in its naturalism, was indisputable evidence of another civilization at work. And thats exactly how the New York Times heralded it on its front page: German Discovers Atlantis in Africa.

The head of the bronze is hollow, reported the Times, and this construction helps to establish the period of the work. It is entirely devoid of Negro characteristics, and there is no doubt that it cannot have been of local casting. Frobenius estimated that it dated back to ages before the day of Solon. It took several paragraphs before the paper quoted a voice of caution, a professor of Greek archaeology and art at Columbia University, James Wheeler, who suggested tepidly that it would seem difficult to prove anything one way or the other about his find.

In fact, the head probably wasnt bronze at all but was made of brass and copper alloys. So taken with his theory of Atlantis living on in Africa that Leo Frobenius wrote a two-volume book on his expedition to promote it. And like Schliemann with Troy or Howard Carter digging away in the Valley of the Kings, he vividly recalled the moment of discovery. He stood for many minutes in front of the sculpture. Then I looked around and saw the blacks, the circle of the sons of the venerable priest... and his intelligent officials. I was moved to silent melancholy at the thought that this assembly of degenerate and feeble-minded posterity should be the guardians of so much classic loveliness.

At the time, Frobenius was celebrated as one of the most respected ethnographers in the world. And, believe it or not, he was even considered a champion of African cultures, suggesting they deserved greater study and respectif you can call his views respectful. He railed publicly at how the British looted the palace of Benin but went home from the Belgian Congo in 1906 with 8,000 artifacts. He extolled the moral virtue of Africans, romanticizing them in noble savage terms, and wrote about the destructive impact of colonialism, such as the rubber trade. Yet he complained to American missionaries about keeping blacks in their place: I want to underscore, explicitly, that I see the Negro as a primitive form of mankind, and it is demonstrable, based on the history of all colonizing nations and on the lives of almost every individual, that if the Negro is deprived of the sentiments of his primitive kind, and if he falls prey to the obscurity of equalization in matters of cultural production, he puts not only the cultural work of the white race, but also himself in great danger.

Such was the racism of the man that he literally failed to recognize that the head he found at Ife displayed black featuresone can recognize them clearly in the plate included in his book. Indeed, they had to have them because the head was sculpted by the Yoruba people in an age before any contact with Europeans.

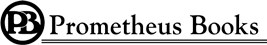

His dating estimate was also way off the mark. But just because the head isnt ancient doesnt mean we cant delight in its brilliance. The walled city-state of Ife thrived between the twelfth and the fifteenth centuries, which means, as art critic Michael Glover once put it, at the same historical moment that Andrea del Verrocchio was doing his wonderfully painstaking, high-Renaissance drawing of a female head, anonymous artisans in Ife were working with brass, bronze, copper and terracotta to produce a series of exquisite heads that are not only the equal of Donatello in technical brilliance, but also just as naturalistic in their refinement.

A terra-cotta bust sculpted between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries by one of the great Ife artists of what is now southwestern Nigeria. Part of the Leo Frobenius collection in 1913.

Frobenius wouldnt entertain this possibility. Like many experts of his time, he subscribed to the grand idea of cultural diffusionthat anything good in civilization originated from the mighty empires of the past in Europe and the Middle East. They were sure that a white residue could be traced in the finest expressions of African culture. But his take on it was unique, creating an elaborate backstory for an African Atlantis. He spent years in the field, acquiring valuable relics and prehistoric stone paintings, studying, gaining knowledge of the indigenous peoples of Nigeria, Sudan, and the Congo, and yet despite some brilliant insights, you often see in his works the rationale of a quack who could have been easily and simply challenged over his assertions.

In one paper, for example, he argued, The Ethiopian Negro culture is not directed as it develops toward some goal or purpose determined intellectually, but on the contrary is guided under the aegis of emotional life. Of course, Frobenius had his own way of defining Ethiopian culture, but even allowing for that, when these words appeared in print in 1928, men from independent Ethiopia journeyed as government-sponsored students to attend the Sorbonne, Oxford, and universities across Europe and in the United States. For Africans abroad, however, he had three questions over whether they have remained true to their nature while in exile ... 1) Is the Negro in a strange culture still capable of emotional exaltation and ecstasy (e.g., in church)? 2) Is the Negro still musical? 3) Has he kept his sense of humor, i.e., has he still a sovereign superiority of soul able to smile without cynicism or mockery at any fate? His paper, by the way, was titled, Early African Culture as an Indication of Present Negro Potentialities.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992