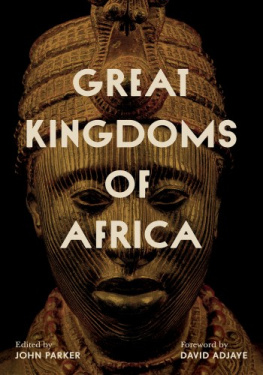

On the :

A copper-alloy figure of a Yoruba oni or king, unearthed at the Wunmonije Compound site in the city of Ile-Ife, Nigeria, in 1938, 13th to 14th century. Height 14 in. (37 cm). The National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Ife, Nigeria, 38.1.1. Photo Andrea Jemolo/Scala, Florence

University of California Press

Oakland, California

Published in the United Kingdom by Thames & Hudson

Great Kingdoms of Africa 2023 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

Foreword 2023 David Adjaye

Introduction John Parker

Text edited by John Parker

Designed by Matthew Young

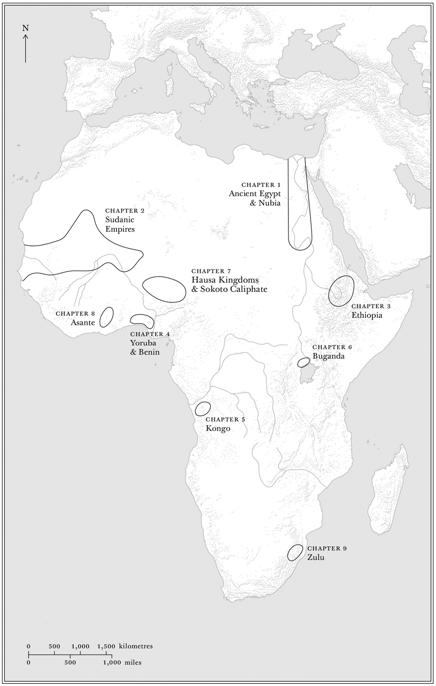

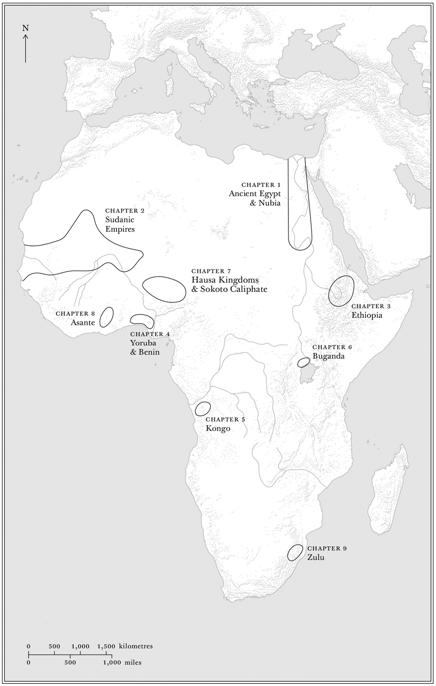

Maps on by Matthew Young

All page numbers refer to the 2023 print edition

Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-520-39567-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022947710

This electronic version first published in 2023 in the United States of America by the University of California Press

eISBN for USA only 978-0-520-39568-8

About the Author

John Parker taught the history of Africa at SOAS University of London from 1998 to 2020. He is co-author of African History: A Very Short Introduction and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Modern African History. His most recent book is In My Time of Dying: A History of Death and the Dead in West Africa.

CONTENTS

While Ghana is my ancestral homeland, growing up in various locations across Africa and becoming attuned to its rich diversity of cultures and histories gave me a distinctively pan-African view of the continent. After this formative experience, I went on to document all fifty-four African capital cities during a ten-year period spent investigating the role of architecture in the making of urban space. This became a study less about the construction of symbolic urban objects than about the synthesis of cultures going back over several centuries. I came to see the city as an inclusive conglomerate of shared identity rather than a series of free-standing architectural icons. A similar ethos drives this book, which seeks to understand African kingdoms not by the usual historical periods, but on their own unique evolutionary terms.

Through my research, it became clear to me that the political map of Africa has distorted our capacity to recognize the diversity of its cultures and the critical role of geography in shaping its histories. I developed a different kind of map of the continent, which became the basis for classifying its capital cities according to their position in one of six geographic terrains. These distinct terrains the Maghrib, the Desert, the Sahel, the Savanna and Grassland, the Forest, and the Mountain and Highveld portray the continent as a place of shared geographical inflections and identities. It is this range of terrains that has enabled such diverse kingdoms to emerge and mutate within a single continental plate.

The map of the African kingdoms in this book can also be seen as a redrawing of the colonial diagram. The edges of these kingdoms appear deliberately imprecise. Like geographies, they are flexible and constantly shifting forces. Applying my geographical methodology to the kingdoms, ancient Egypt and Nubia would fall under the category of Desert; the Sudanic empires between Desert and Sahel; Ethiopia predominantly Mountain and Highveld; the Hausa kingdoms and Sokoto Caliphate Savanna and Grassland; and Zulu between Grassland and Mountain and Highveld. The other four kingdoms could all be considered as falling within Forest territory: Yoruba and Benin, Buganda, Kongo and Asante. This reflects the contemporary situation, where the Forest region has the largest number of capitals, many of which are port cities. While the forest itself has often been cleared, the combination of heat and moisture and consequent settlement patterns still determine the character of these places.

This book offers a critical reclaiming of African kingdoms. It looks anew at these historic regions and understands systematically the relationships between them. Their identities are intertwined physically with features such as rivers and lakes; spatially with urbanization, temples and tombs; and materially with things such as gold and art. A key part of this process of reclaiming narratives is to understand the long histories and ongoing trajectories of these kingdoms.

For as long as I have practised architecture, I have been fascinated by indigenous civilizations. I am interested in the root essence of places. My work is developed out of a particular set of circumstances and an interrogation of contexts. I think of architecture as constructed narratives, by which I mean making buildings in deep dialogue with both time and place. This entails constructing buildings that acknowledge their histories, while creating something entirely new to serve communities into the future. Two of my projects in particular engage directly with the narratives of African kingdoms: the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (completed in 2016), and the Edo Museum of West African Art in Benin City, Nigeria (ongoing). In my mind, they have a dialectical relationship: the former is about a reconciliation of our present, the latter speaks to a recovery of our past.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture addresses this present condition and the evolution of the African diaspora. It occupies what was the last vacant site in Washingtons National Mall, a symbolic place and a charged landscape. Celebrating the importance of the Black community in the social fabric of American life, I designed the corona structure an inverted pyramid form taking inspiration from a triple-tiered crowned sculpture created by the famous Yoruba craftsman Olowe of Ise (c. 1873c. 1938). This silhouette has since become the primary register for the building, which relates the diaspora so profoundly to their origins in Africa. In contrast to its neighbours made of stone and marble, it is also the National Malls only metal building, which is in part a reference to the bronze and copper traditions of Benin. In so many ways, the museum brings a certain tangibility to the remarkable contribution of the African American community.

The Edo Museum of West African Art is a key element in a project aimed at the restoration of Benin City, the capital of one of the continents most ancient kingdoms. To be situated adjacent to the Obas palace, the epicentre of the kingdom of Benin, the museum will house repatriated artefacts and art seized during the British colonial conquest of 1897. Given the significance of this project, the museum is envisaged as part of a larger masterplan that will excavate, preserve and restore Benin Citys extensive system of earthwork walls punctuated by moats and gates. I designed the new museum to connect to the citys extraordinary earthen landscape, its orthogonal (or right-angled) walls and its courtyard networks. The museum will be a set of elevated pavilions, taking their form from the very fragments of these historic compounds. I want Benin City to regain its position as an artefact in and of itself. I see the Edo Museum as a re-teaching tool a place for recalling lost collective memories and to instil an understanding of the cultural foundations of Africa.

From my Accra office, I am now involved in the making of other civic buildings across Africa, which I approach in a similar way to the Edo Museum: using architecture to illuminate history and form collective identities. On a personal level, I have also returned to my ancestral land in the Akuapem hills of Ghana and constructed a country home for myself in my fathers village. To be rooted locally, I designed it using rammed earth and it has been constructed organically. I am entirely preoccupied with thinking about the elemental quality of earth, our co-relationship with nature and the origins of Black architecture. Like this book, I believe my return is a process of going back to the past to reconstruct the future.

Next page