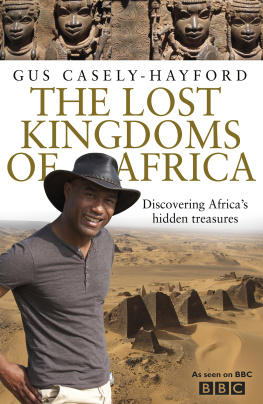

About the Book

For many of us the history of Africa is, at best, vague. We might think of Egyptian pyramids, legendary queens and Zulu warriors. The truth is of course much more diverse, creative and culturally rich. In The Lost Kingdoms of Africa, Gus Casely-Hayford takes us on a fascinating journey through the history of this remarkable continent. We will encounter archaeological sites of staggering beauty that rival the Great Wall of China, vast and ancient universities that pre-date Oxford and Cambridge, kingdoms of extraordinary wealth, artistic traditions that still inspire artists today, great religious sites that surpass the Vatican, and a country with more pyramids than Egypt.

In recent years, new archaeological and anthropological research has opened up the study of African history in ways previously unimaginable. Long-lost kingdoms are being brought back to life. Civilizations that had faded into myth are revealing their secrets. Using this latest research, Gus Casely-Hayford is able to tell the story of Africas major kingdoms in an entirely new, colourful and richly informed way.

Accompanying a major BBC series, The Lost Kingdoms of Africa is both a major addition to our understanding of this oft-overlooked history and a genuine source of delight and wonder.

Contents

For my dear Sascha, Sarah and Mother

Under the veranda of the Obas Palace: detail of Benin Bronze. (Drawn by Gus Casely-Hayford)

Introduction

There is a wooden bench in the basement of the British Museum. It is not a particularly comfortable spot to spend any length of time. The seat is low and hard so joints have to adopt awkward angles to compensate. But I somehow find myself returning there, to sit, to reflect, to be; but mostly just to look. I return to the spot to be among the Benin Bronzes and the Ife heads, a rooms worth of mysterious and controversial figurative brass plaques and busts that have intrigued and troubled generations of Western historians, anthropologists and ethnographers. Over the years I have felt a growing closeness and familiarity with these pieces. Like so many other African objects in Western museum collections, they exude a confident beauty. But there are aspects of their histories, their original use and context, that are frustratingly and enduringly obscure.

Mystery can be an important component of beauty, but ancient African history is an area of cultural studies with a suffocating surfeit of unknowns. A lack of knowledge, a dearth of evidence, of corroboration, have choked the subject, in some areas threatening the integrity of meaningful study. Beyond the unquestionable aesthetic merit of the Ife heads, there is plainly a great deal more to these objects; layers of narrative and context that have for the most part been lost. And while sitting on a bench filling the void with romantic interpretation can be thrilling, frustration at being left with both profound and basic questions about such iconic objects remains.

So I return to this bench to replay a mute discussion with the bronzes and Ife heads. I ask the same questions on every visit, questions posed by generations of historians to so much African material culture: why, when, how, and who? Over the years I have felt those big ambitious queries slipping to the status of moot rhetorical incantation. But perhaps things have begun to change. I believe that we have reached a defining moment in our understanding of African history. There are burgeoning innovations in thinking that will allow different histories to be constructed. New technologies and perspectives are being brought to bear in pursuit of a more profound, perhaps more sensitive understanding of the early history and ancient civilizations of Africa.

I began my relationship with the Benin Bronzes and Ife heads during the summer of 1976. I was still at school but I had already developed a voracious appetite for African culture and colonial history. It was a period when a pioneering generation of post-colonial historians, academics who sought to redefine history free from the lens of imperialism, were still the intellectual custodians of the subject. They wrote for the most part, with profound disappointment, of the shattered dreams and unfulfilled promise of a broken continent. But beyond new theories of history, Africas material culture was different. Artefacts from ancient artistic traditions stood out as tantalizing glimpses into the past. I can remember reading about the Ife heads as glorious enigmatic objects of such beguiling, startling beauty that they could almost overcome the contextual void that surrounds them by speaking to us directly. So I set out to the British Museum to see them.

It was a gloriously hot summer and I felt every degree of that heat as I squirmed back down the steps beneath the portico of the British Museum following a short and unsuccessful visit. I had been told at the information desk that Africa, Asia and other material culture of the former colonies was not held at the Great Russell Street site; objects like the bronzes were housed in the Museum of Mankind. When I asked why the bronzes were not side by side with the other great cultures, I was informed that in a dedicated building there was more space to explore their particular complexity. Even at twelve I was not convinced why was Egypt then exhibited in the British Museum just as part of the Western canon?

As I wandered around the Africa collection at the Museum of Mankind and eventually found the bronzes, I began to understand for the first time the role of a curator and a historian. The story of mute objects could be profoundly important to the living. In the absence of evidence, interpretations of these ancient things could become corrupted and contentious. Mystery, while romantic, could also offer cover to tainted perspectives and bad history. How could we sort the truth from the monstrous black hole of unknowns that threatened to engulf the subject?

Standing among the bronzes, I became overwhelmed by a feeling of cultural disorientation. I had come in search of a story in which I could see something familiar, but I was left with a range of questions. It felt personal. I was reminded of the emotional confusion Id felt while going through my fathers belongings after his death. On the top of a wardrobe Id found an old suitcase; inside was a small box and two old rolls of cloth that smelt of petroleum jelly, paraffin and palm oil. I opened the box, and inside were dozens of letters and photographs of people unknown to me. I looked at each picture, each one an enigma. I tried to read each image as an artefact, as a piece of archaeology. Each tear and wallet-crease, the smell, the traces of termite and foxing, and an inscription on the back were all potential clues, but like the figures in the bronzes, they seemed to say very little. Strangely, rather than making me feel closer to anything or anyone, I felt distanced. In the same way, my physical closeness to the bronzes only made more stark the distance and barriers that obscure these objects. Up close you could sense that someone had laboured to make them, finessed and refined the metal to tell a particular story, but why, when, how, and who? I wanted to give back to the objects something of their story, their context, their due respect. While I felt frustrated, I also felt an unwarranted emotional connection to these things. We had both lost histories.