Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

Dedicated to Joe

The Publisher would like to thank the following for the illustrative references for this book: Endpapers: The British Library Board; : Stirton/Reportage/Getty images.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed; however, if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright Gus Caseley-Hayford

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Angelo Rinaldi

ISBN: 978-1-405-93491-6

Gus Casely-Hayford

TIMBUKTU

with illustrations by

Angelo Rinaldi

City Beyond Reach

For centuries, it sat as a frustration: a jewel that lay defiantly beyond Europes grasp. Unlike El Dorado, road-hardened merchants were confident that this conduit to the vast gold reserves of the Mali Empire existed.

Timbuktu was a prize that Europe coveted.

In 1618, a company was founded in London with the primary objective of building a trading relationship with Timbuktu. It would fail. As would generations of Europeans, their expeditions ending in murder, bungling, confusion some simply disappearing without trace. The catalogue of calamity was long and tragic. In 1620, Englishman Richard Jobson mistook the River Gambia for the Niger; in 1670, Paul Imbert, a French sailor, was kidnapped and murdered en route; John Ledyard, an American, died in Cairo in 1789, before his expedition had even really begun; Daniel Houghton, an Irishman, simply vanished after leaving Gambia; and Frederick Horneman, a German academic, perished on the banks of the Niger. Even Mungo Park, one of the most celebrated explorers of any age, was to drown in the Niger under a hail of spears in 1806.

Timbuktu held its secrets dearly.

The first Westerner to return claiming to have seen Timbuktu, a shipwrecked African-American, Benjamin Rose, was kidnapped and taken to the city under duress in 1810. Rose was followed by Major Gordon Laing, who traversed the Sahara, reaching the city in 1826 only to be killed before he could return home. Laing was followed in 1828 by Ren Cailli, the first European to return alive, opening up the city on the edge of the Sahara to the West.

Geography

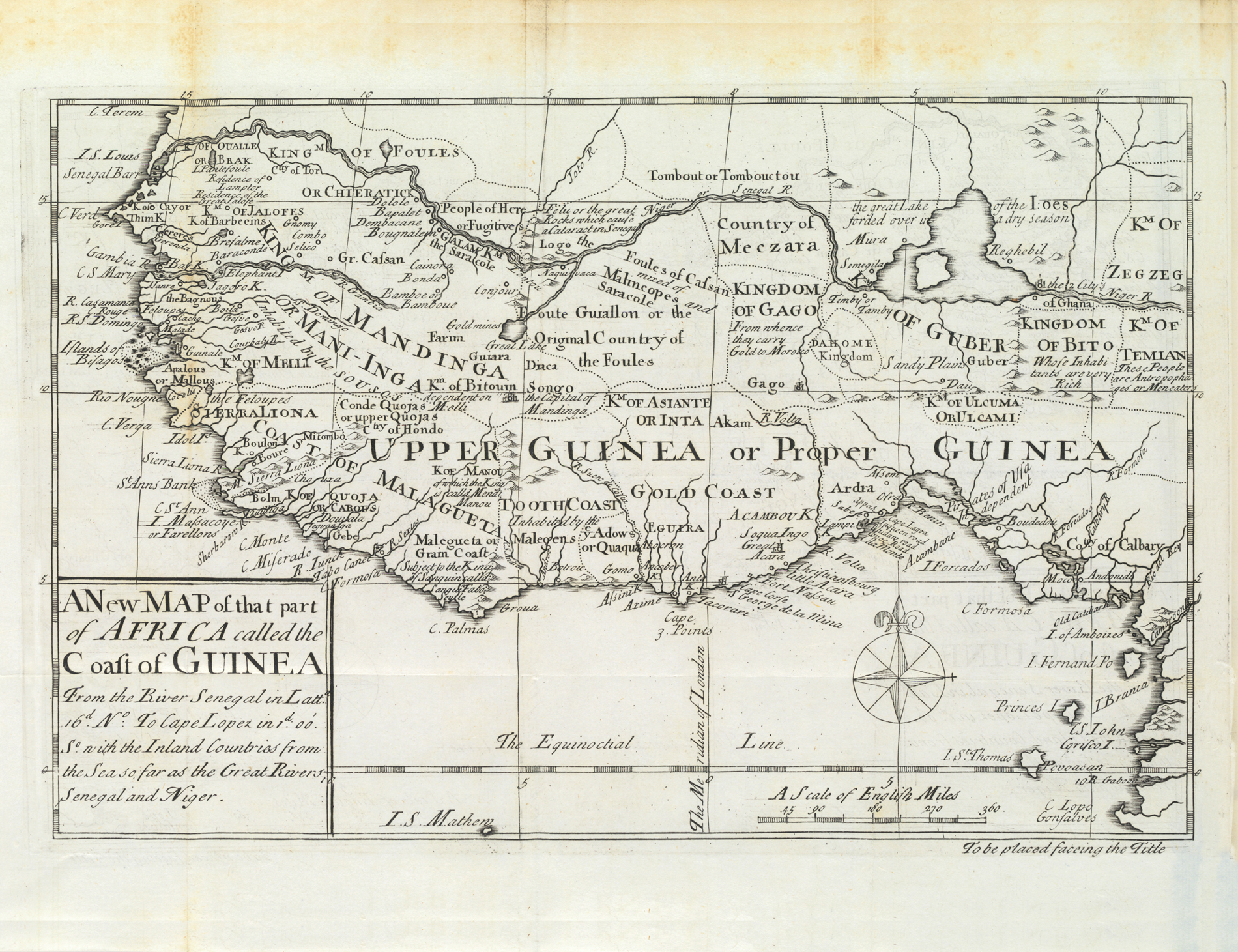

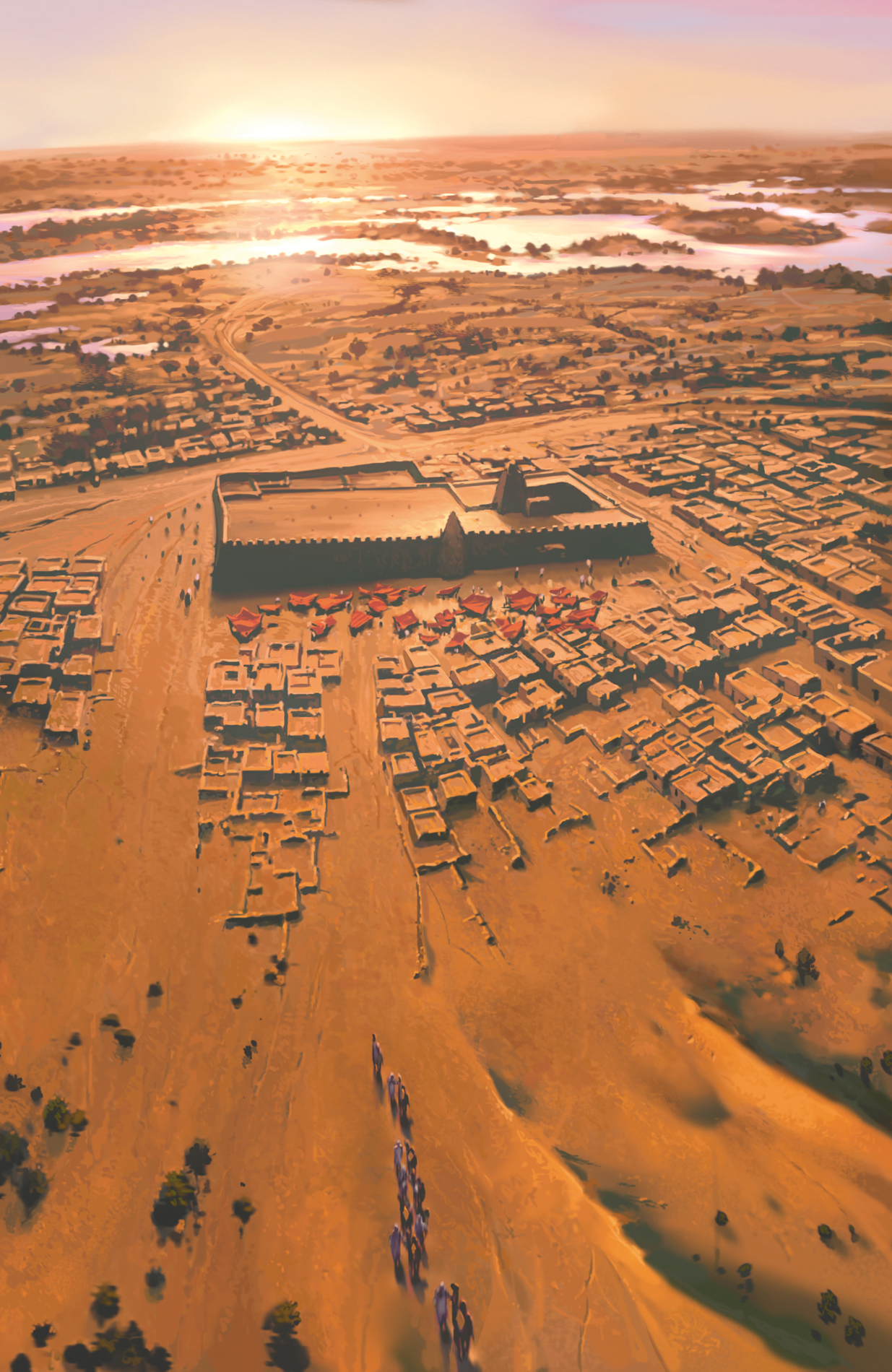

The River Niger is a remarkable piece of geography flowing away from the sea, it draws its strength on the Guinea Highlands of West Africa, pulling clusters of streams into a single unanswerable body of water. It descends from a lush plateau, slowing as it winds northward through forested regions, across plains in defiance of formidable heat and topography. Languorously, it then pushes on towards the Sahara Desert, until at its most northerly point, it seasonally bursts into flower, disgorging vast amounts of water and silt across arid plains to form a life-giving delta in one of the most unforgiving landscapes on Earth: the Middle Niger, a green corridor of fertile land within which an empire could grow and thrive. And sitting on the ring finger of the River Nigers outstretched hand, was the jewel of the medieval world: Timbuktu.

Perfectly positioned on the desert frontier of the Mali Empire, Timbuktu grew to become a wealthy port for traders from across the Sahara, a gateway for West African goods that sought markets across North Africa and beyond. Yet, it was almost always more than just a place where sub-Saharan dealers in gold and copper could encounter traders conveying salt and spices southward. It also became the market for the exchange and development of ideas. It sat on the edge of a body of sand the size of the US, a desert that separated some of the most economically aggressive and culturally confident states of the medieval age. It was the perfect conduit between worlds, a place where Sudanic and Sahelo cultures, desert and tropic, came together to conceive something exceptional.

But this passage of history begins before the development of the Mali Empire and the transformation of Timbuktu.

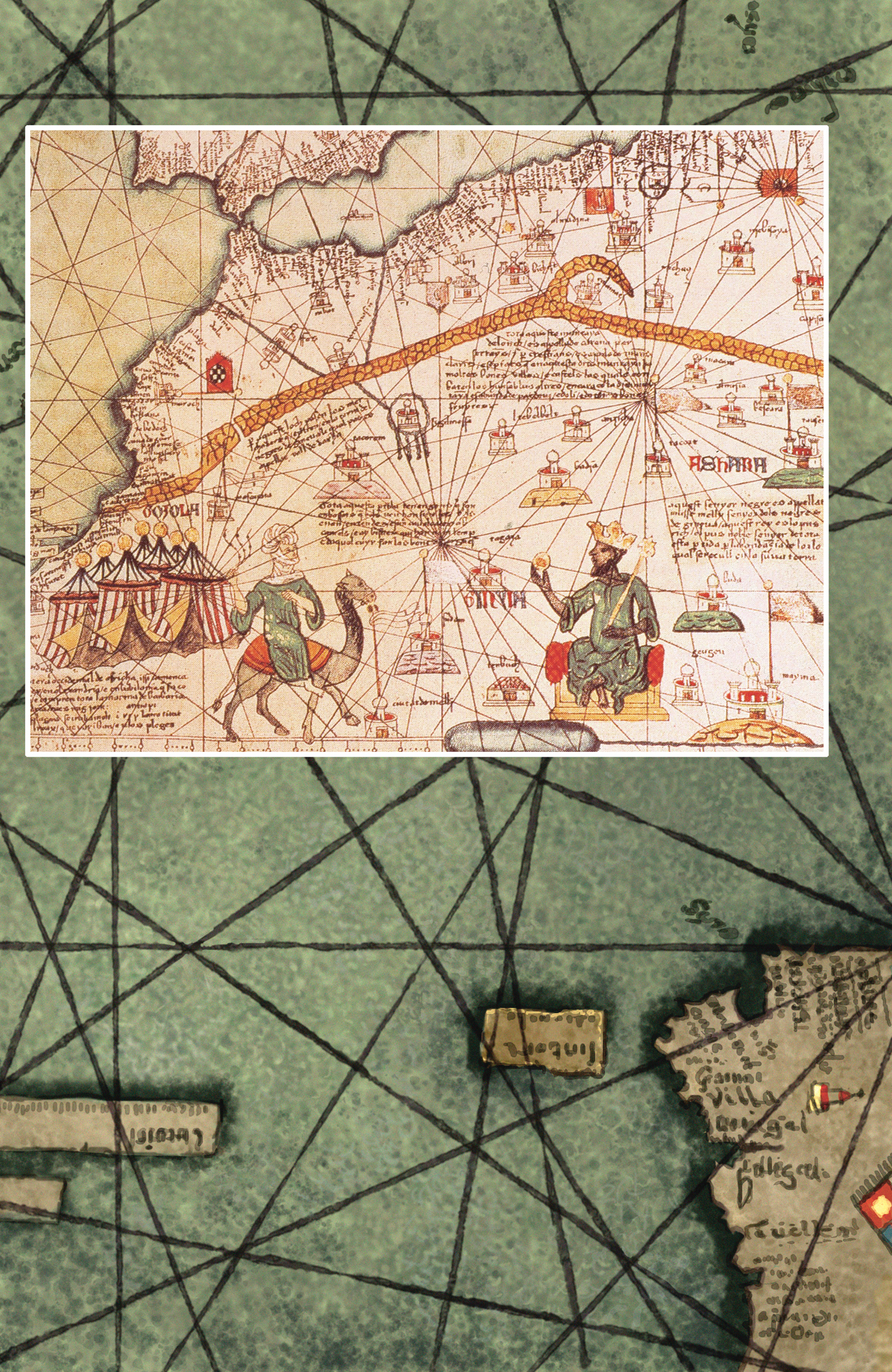

A part of the Catalan Atlas, c. 1375.

Rise and Fall of Ghana

With the rise of the great North African Berber Muslim dynasties from the seventh century came the opening up of ancient routes across and around the Sahara to a new generation of entrepreneurs. The introduction of the camel offered opportunities to exploit trans-Saharan trade at a level of intensity that was utterly transformational. The gold-rich region beneath the northern arm of the River Niger flourished. When Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi, the ninth-century Persian intellectual (who shaped thinking in mathematics, astronomy and trigonometry) rewrote Ptolemys second-century Geography, he included amongst the new additions the Kingdom of Ghana.

In 1068, the Cordoban Muslim scholar Al-Bakri wrote, The King of Ghana, when he calls up his army, can put 200,000 men into the field, more than 40,000 of them archers. The King levied tax on all imported salt and gold, allowing his subjects to sell gold-dust, but securing all gold nuggets for the crown. This was a powerful, well-governed state that practised a variety of forms of religion, but at court and in trade the ascendant religion was Islam, and the King seemed tolerant of this.

However, many of Ghanas neighbours were not comfortable with this cosmopolitan, liberal state growing rich on their efforts, particularly their ideologically conservative trading partners on the far side of the Sahara, the Berber Almoravids. When, in 1076, the Almoravids attacked, the armies and resources of the Ghana Kingdom were simply no match for their northern neighbours. With trade routes compromised and weakened by competition, and suffering unprecedented drought, the Ghana state began a long, slow demise.