Timbuktu

Also by Marq de Villiers and Sheila Hirtle

Sable Island: The Strange Origins and Curious History of a DuneAdrift in the Atlantic

Sahara: The Extraordinary History

of the World's Largest Desert

By Marq de Villiers

Windswept: The Story of Wind and Weather

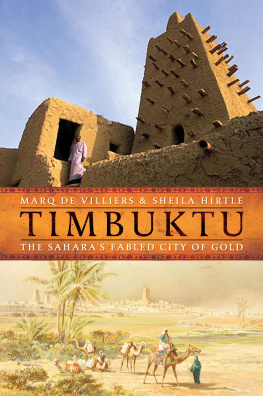

Timbuktu

The Sahara's Fabled

City of Gold

Marq de Villiers and Sheila Hirtle

Copyright 2007 by Jacobus Communications Corp.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

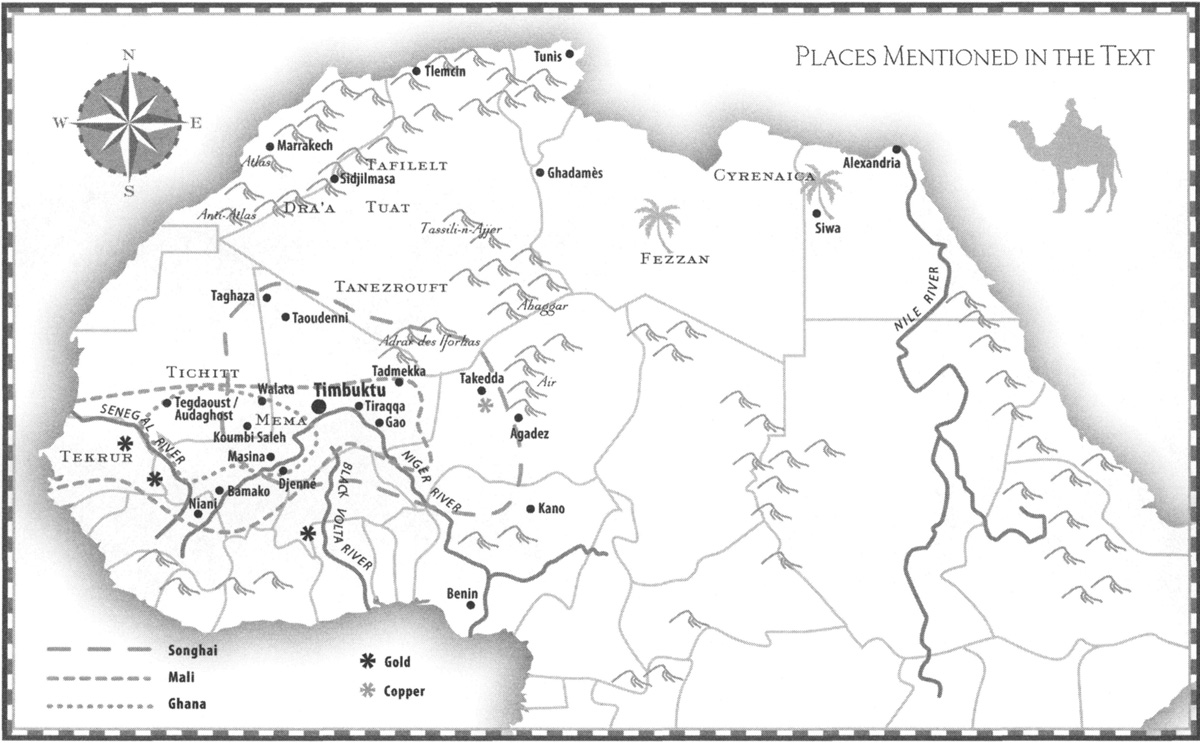

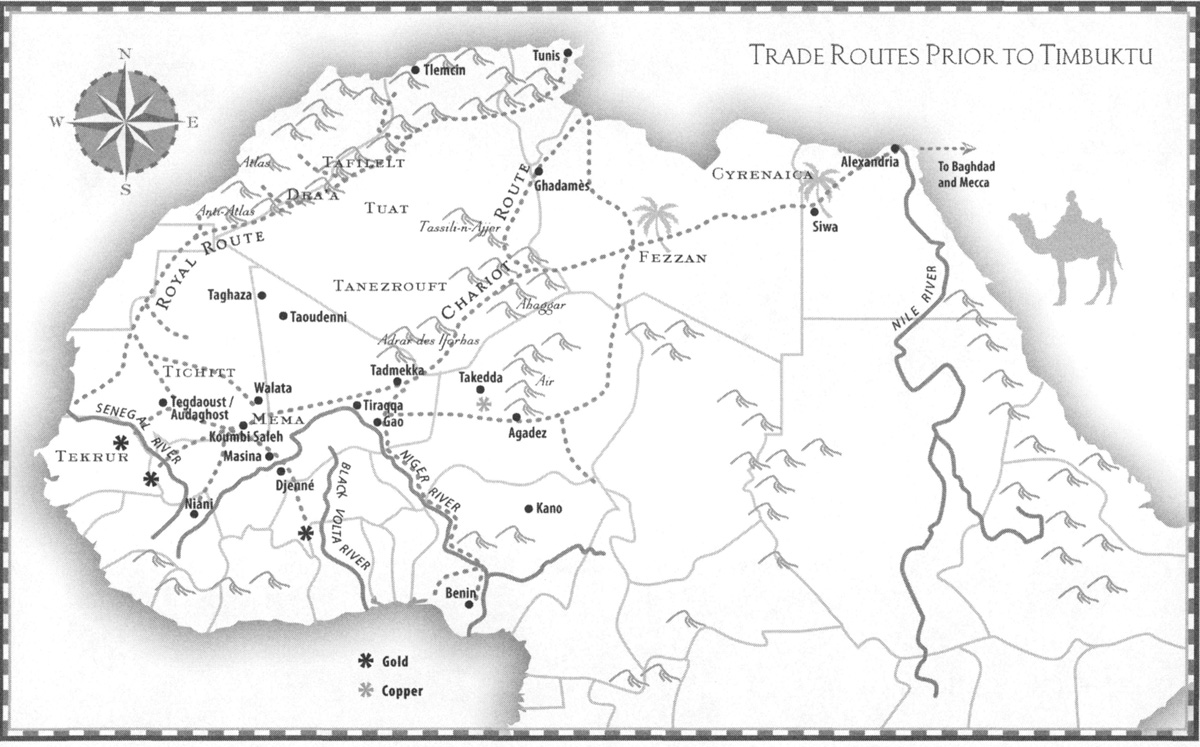

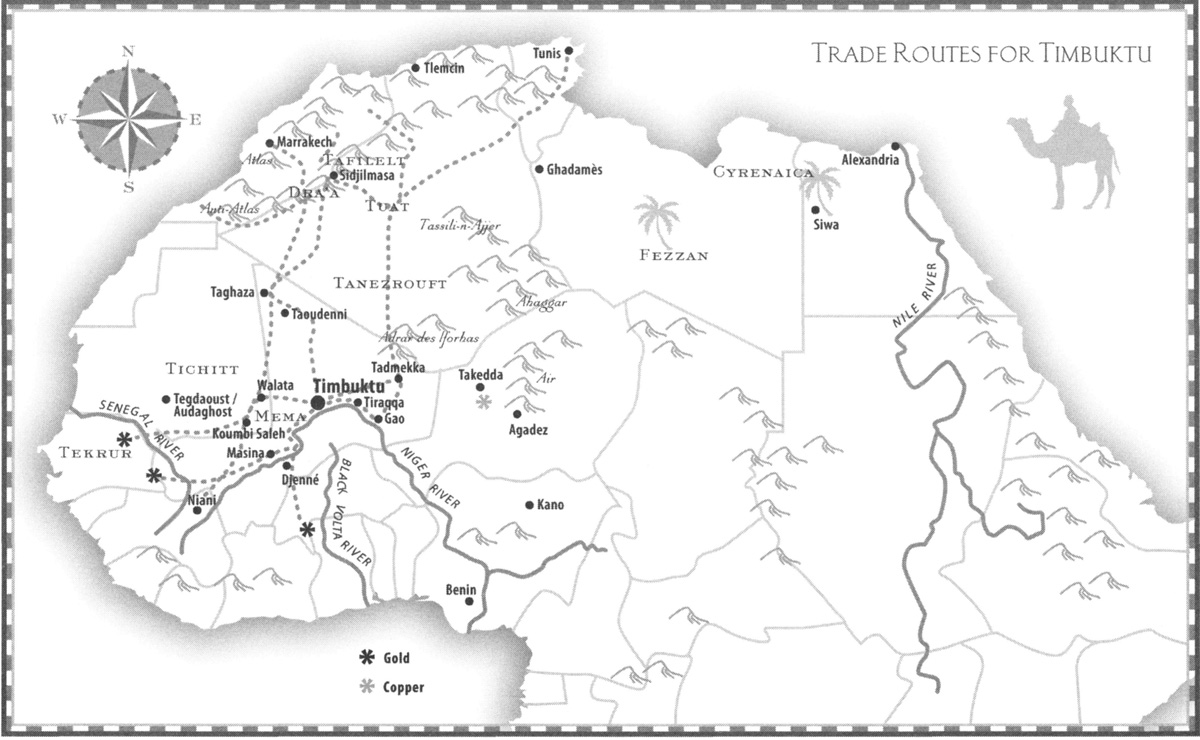

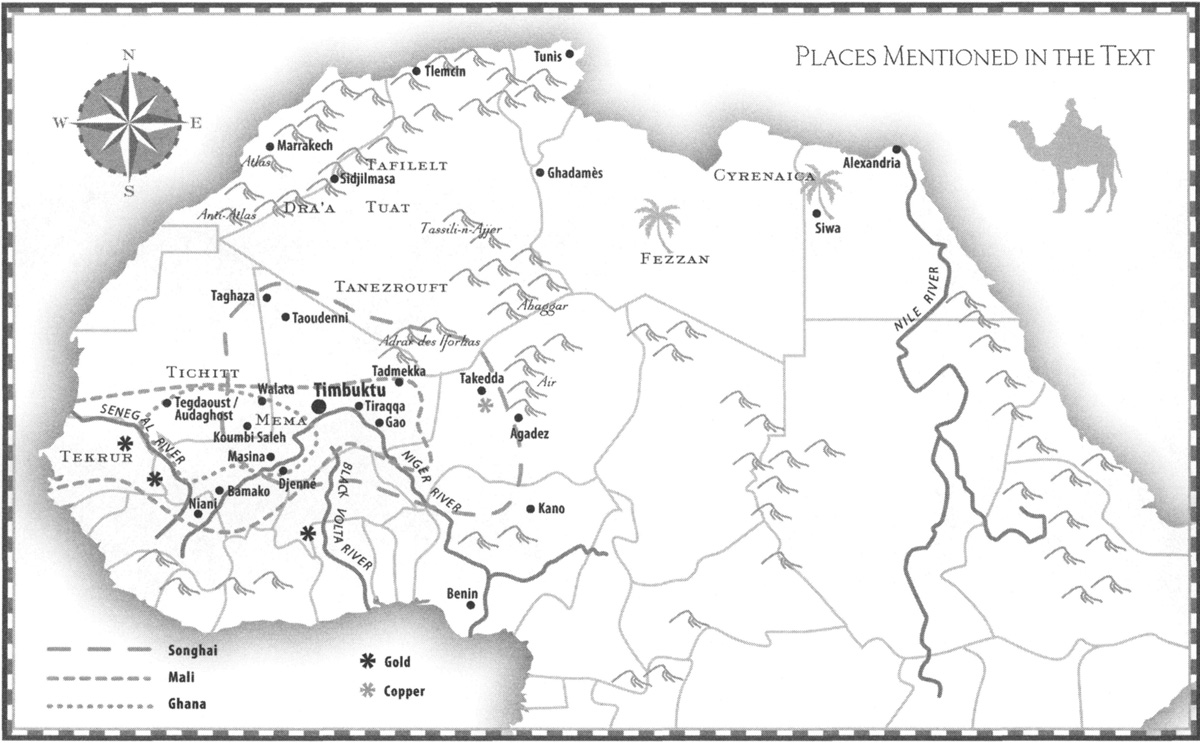

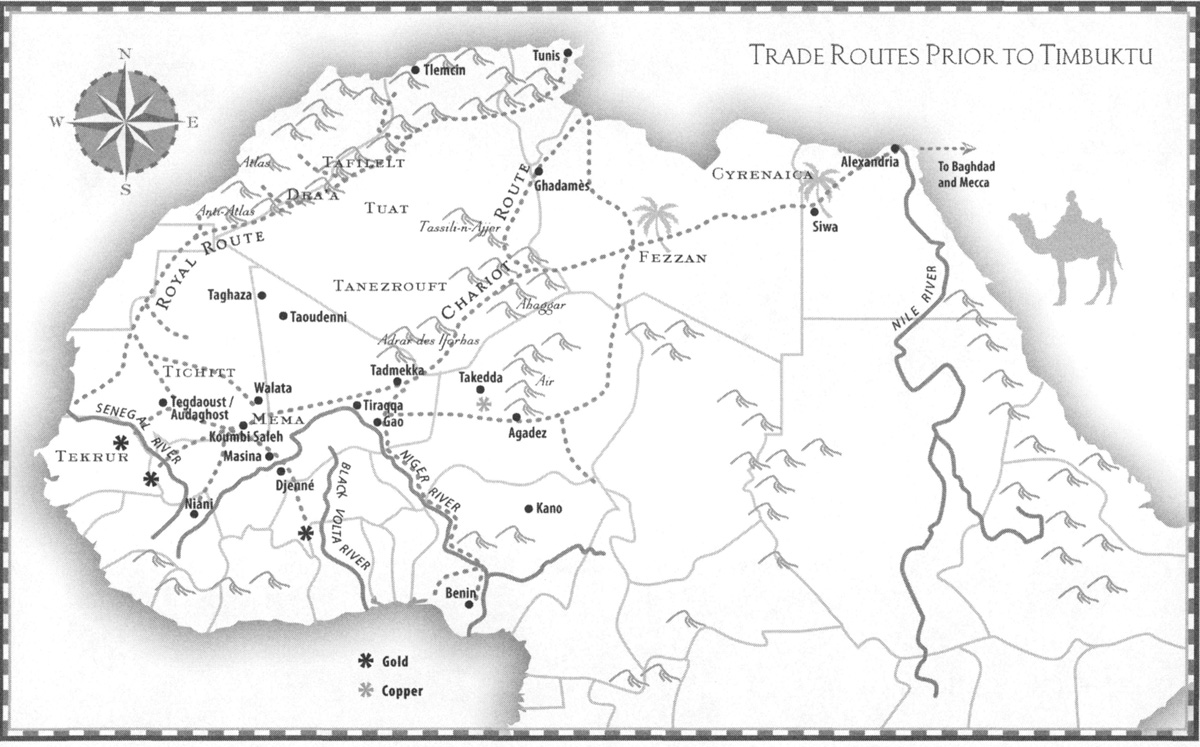

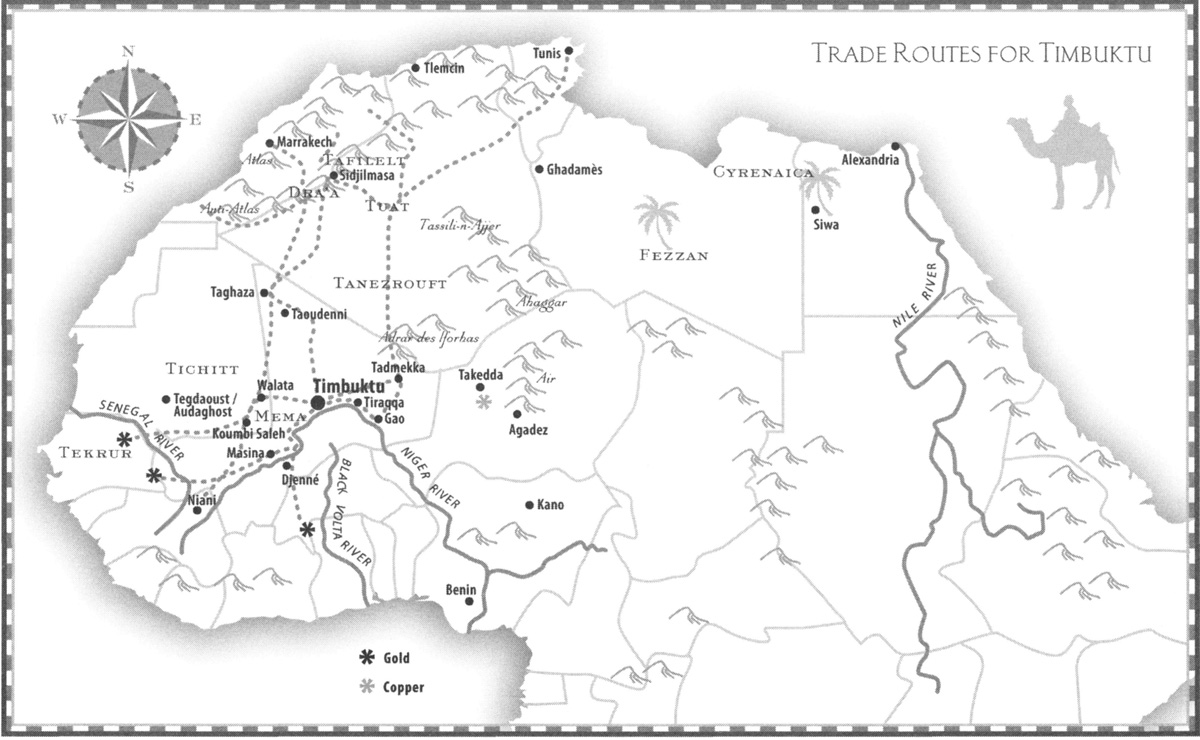

Maps by Dereck Day.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71830-3

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

First U.S. edition 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, and silver from the country of the white men, but the word of God and the treasures of wisdom are only to be found in Timbuktu.

West African proverb

If I were a cassowary

On the plains of Timbuctoo,

I would eat a missionary,

Cassock, band, and hymn-book too.

Impromptu verse, ascribed to Bishop Samuel

Wilberforce 1805-1873

O City! O latest Throne! Where I was rais'd

To be a mystery of loveliness

Unto all eyes, the time is well-nigh come

When I must render up this glorious home

To keen Discovery: soon yon brilliant towers

Shall darken with the waving of her wand;

Darken, and shrink and shiver into huts,

Black specks amid a waste of dreary sand,

Low-built, mud-wall'd, Barbarian settlements.

How chang'd from this fair City!

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Timbuctoo

Contents

MANY PEOPLE HELPED us along the way, and we are grateful for their hospitality and their willingness to share their knowledge. Particular gratitude must go to Sidi Salem Ould Elhadj, chevalier de Vordre nationale of Mali, a man steeped in history, with a wonderfully infectious love of his ancient city. A few years ago Sidi Salem gave a lecture to a university audience in Washington, D.C., on the golden age of Timbuktu but found to his chagrin that his listeners wanted only to know his views on Islamic fanaticism. He was not discouraged and is still willing to share his deep knowledge of Timbuktu's traditions and legends. Important also was Abdel Kader Haidara, proprietor and manager of the Mamma Haidara Library of ancient documents, and a key member of the Conflict Resolution Group, which was set up in homage to Timbuktu's traditions of tolerance and peace. We are grateful for the hospitality he extended us and for the glimpse he gave us of his extraordinary inheritance. We are grateful also to the Tuareg Halis, more properly known as Mohamed al-Hassan al-Ag Moctar dit Halis, and to Shindouk, or Shindouk Mohamed Lamine Ould Najim, chief of a Berabiche tribe, both of whom know the desert intimately but are also comfortable in the universe of the World Wide Web; to Miranda Dodd, who has adopted Timbuktu as her home and whose character reminded us once again why the Peace Corps was such a good idea; to Sidi Mohamed Ould Youbba, director general of the Ahmed Baba Center, and to Djibril Doucoure, the center's director of conservation and restoration, both of whom were endlessly willing to share their knowledge; to Abderhamane Alpha Mai'ga, managing director of the Hendrina Khan Hotel in Timbuktu, who taught us much about the city's long traditions of tolerance; to the Dicko brothers, Litini and Malick, for their hospitality; to Shamil Jeppe of the University of Cape Town, for telling us part of what the story is about; to Tahara Baby for her hospitality. And finally to John Hunwick, whom we have never met, but whose copious writing fills all the interstices of Timbuktu historiography, the kind of oversize presence that is greatly reassuring in these anti-intellectual and intolerant days.

Note to Readers

Alert readers will notice that sometimes the pronoun "I" appears in the text, although there are two authors. Unless otherwise specified, this "I" is Marq de Villiers. Two of us produced this book in equal measure. We both sojourned in Timbuktu. Otherwise, the travel into the archives, libraries, and technical journals was done mostly by Sheila Hirtle, the travel in the hinterlands of Timbuktu, and the consequent anecdotes and conversations, mostly by Marq de Villiers.

Dreaming Spires of Gold,

Under the Desert Sun

ABDEL KADER HAIDARA'S Timbuktu home sprawls off an unnamed sandy alleythey're all sandy in Timbuktu, and none of them are namedin the southeast quadrant of the city. We pulled up outside its walled courtyard late one winter afternoon; children were playing in the sand outside, building corrals out of twigs and dried goat dung, the source of the dung being tethered to a stake nearby. In the courtyard a graybeard sat companionably by, chewing rhythmically, and two women pulled and pounded at a laundry tub. Inside, the windowless main living room was sheltered from the sun, turquoise and cool, with carpets on the floor and red plush banquettes; the walls were lined with bookcases and cabinets and a hulking television set. Our host was there with an uncle and a friend; with us was a young Tuareg called Mohamed al-Hassan al-Ag Moctar dit Halis, usually just known by his nickname, Halis (which is an affectionate mother's "My Little Man" in Tamashek, the language of the Tuareg). It was Halis who introduced us. He was there as interpreter, though he was not needed; the urbane and ever-courteous Sidi Haidara spoke fluent and effortless French, among many other languages. After the first pleasantries, the conversation ranged from the legends about the founding of Timbuktu, through the golden age of the city, to its gradual decline after the Moroccan invasions, some four hundred years ago. It's not too much to say that the city has been slowly declining ever since that invasion, for most of those four hundred years.