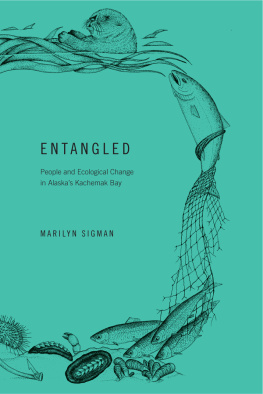

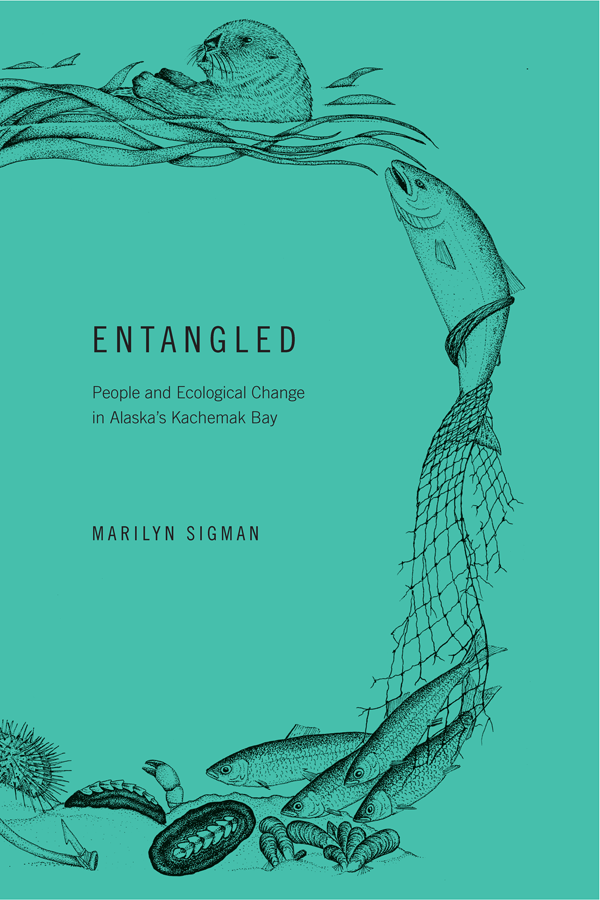

Entangled is a profound meditation on how the inhabitants of Kachemak Bayhuman and nonhuman alikehave reckoned with the ebb and surge of cultural and ecological changes through time. With the curiosity of a biologist, the doggedness of a detective, and the eloquence of a poet, Marilyn Sigman beautifully deciphers a landscape marked by abundance and scarcity, stability and disruption, loss and resilience, memory and story. The fascinating result is a scientific whodunit, a natural and cultural history, a deep map, an elegy, and, above all, a love letter.

Sherry Simpson, author of Dominion of Bears, winner of the 2015 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Natural History Book

Marilyn Sigman unites her science brain with her naturalists heart and an insatiable curiosity to bring us a beautifully written account of human and ecological connections. Part memoir, part natural history, part quest into understanding the nature of changeEntangled will delight not just readers intrigued with Alaskas resource and cultural history but all those concerned with what it means to know and honor a home place.

Nancy Lord, former Alaska Writer Laureate, author of Fishcamp and Beluga Days

Like creatures in an ephemeral tide pool, our lives are shaped by forces both within and beyond our control. In Entangled, Marilyn Sigman shows us that life is messy, shift happens, and riding the waves of change is best done with a steady kayak, muck boots, and an inner compass.

Amy Gulick, photographer and author of Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaskas Tongass Rain Forest

In these pages Marilyn Sigman sweeps us along a path of personal discovery. This memoir is steeped in fast-moving, wondrously descriptive stories centered on the biology and archeology of the Kachemak Bay region of Alaska within the context of her personal and family history. Whether it be the investigation of the sea otter and the bidarkis role in shaping shoreline ecology, or the chain of environmental fallout precipitated by a recent ocean warming event (the Blob), or her telling of the spiritual and environmental story of the Kachemak people and their sudden mysterious disappearance, Sigman constructs a far-reaching picture of sometimes sudden historic and current environmental change. With great detail and the personal insight that comes from looking closely at the world around her, she draws us into the story behind the changes and their larger implications. Sigman has crafted a must-read for both local and visitor.

Craig Matkin, marine mammal scientist and director of the North Gulf Oceanographic Society

Text 2018 University of Alaska Press

Published by

University of Alaska Press

P.O. Box 756240

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6240

Cover and interior design by 590 Design.

Image credits:

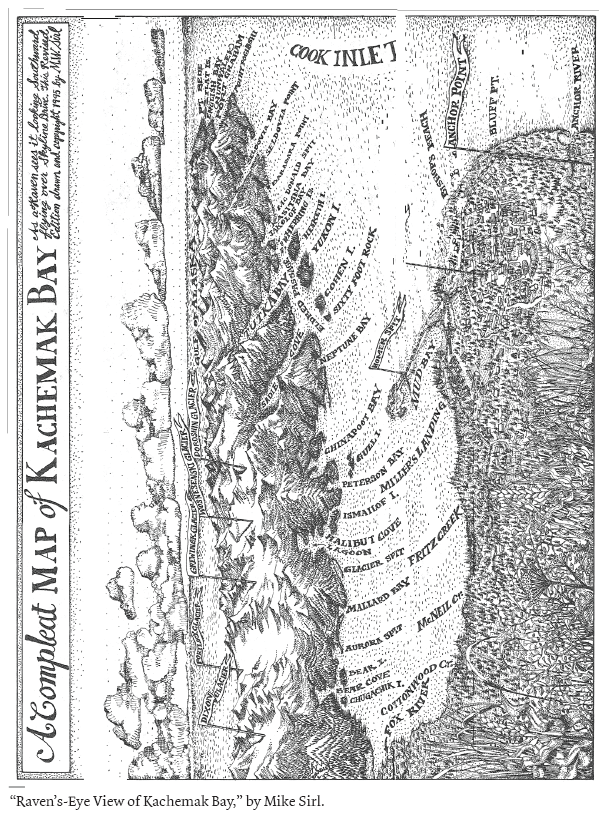

: Bidarki (aka katy chiton) by Conrad Field

: Kachemak lamp by Kim McNett

: Halibut by Conrad Field

: Otter carving by Kim McNett

Cover art by Conrad Field.

Text by Weeden and Steinbeck printed with permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Sigman, Marilyn, author.

Title: Entangled : people and ecological change in Alaskas Kachemak Bay / by Marilyn Sigman.

Description: Fairbanks : University of Alaska Press, [2018] | Includes index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017031753 (print) | LCCN 2017048212 (ebook) | ISBN 9781602233492 (ebook) | ISBN 9781602233485 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Climatic changes | Alaska | Kachemak Bay Region. | Ecology | Alaska | Kachemak Bay Region. | Kachemak Bay (Alaska)

Classification: LCC QC903.2.A37 (ebook) | LCC QC903.2.A37 S54 2018 (print) | DDC 577.27/6097983dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031753

Dedicated to the memory of my father,

Leo Sigman,

who took me fishing

All Alaskans must come to terms with the central problem of how a contemporary society can function harmoniously within arctic and subarctic environments. Harmonious function implies a deep and true knowledge of those environments and human interactions with them.

Robert B. Weeden, Messages from the Earth: Nature and Human Prospect in Alaska

Part I

SHIFTING BASELINES

ARRIVING

I sit beside a roaring stream of water that pours through a gully toward the lip of a waterfall and plunges to the beach below. The water clatters with rocks, so loud it fills my mind. I feel its flow from the top of my head to my toes. Remaining stationary requires resistance to the seaward pull that carries torrents of soil, leaves, needles, blossoms, branches, and whole trees downward.

How could I ever hope to find peace and stillness in this place that is always in motion? This place could sweep me away in a seismic moment or wear me down slowly, drop by drop. The physical forces of the world move me just as surely as they move rocks and water. In this long rushing moment, I can barely stand firm and resist becoming part of the flow.

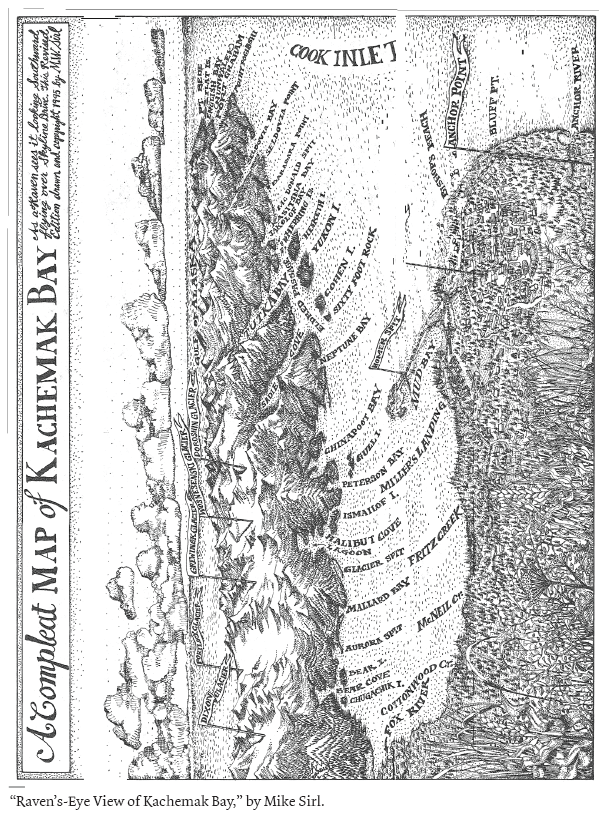

Kachemak Bay is an edgy place. It straddles the edges of lands scarred by glaciers. The cooled ash of volcanoes is interwoven with the leavings of streams that meandered the landscape for millions of years. Glaciers and streams wrote their chapters into this land. The volcanoes provided punctuation, and an entire book lies beneath the rubble, written huge by the patterned, heaving rhythm of the worlds tectonic heart. Beyond a southern horizon of peaks, the Pacific Plate nudges the North American Plate in the many-fathomed Aleutian Trench. The plates lock up and then bolt into earthquakes. The Pacific Plate dives down and bubbles back up as fiery lava.

The name Kachemak is derived from Native words ka, water; chek, cliff; and mak, meaning large, high, or great. It was Highcliff Bay on the earliest American maps and chartsuntil Kachemak Bay stuck in 1896. One persistent local legend is that the word translates as smoky bay, for the place where fires burned and smoldered in coal seams for decades. Homer, its largest town now, lies on the north shore with cliffs above the beach in either direction. Coal miners and fishermen, homesteaders and tourists, scientists and artists, Russian Old Believers and Methodists have all called it homeand Homer. No poet, Homer Pennock founded the town in the best tradition of Alaska conmen, leaving with the dough to die penniless in New York after one scheme too many. Now, the cabin hippies chop firewood, haul water, and homeschool their children. An advancing front of retirees shares the million-dollar views. Here the road ends.

The water shape-shifts, from bay to fog and cloud and back to the bay again as rain or snow. Currents and tides arrive from the south and depart to the north in a great counterclockwise gyre spun up by the moon and the revolving planet. The tides, with a range that is among the most extreme on Earth, are two enormous in-and-out breaths every day. The land recedes in trickles and sudden slips. During the melt season, the bare slopes of the bluff are strewn at their gully knickpoints with eighty-foot-tall spruce trees. They point down toward enormous piles of rocks and soil covered with vegetation that traveled so quickly that fireweed remains in bloom.

The boundary of land and beach and water shifts, changing slowlytide by tide, storm by stormor suddenly. The 1964 earthquake caused the bottom of the bay to drop by six feet in ten minutes, and the entire planet rang like a gong. It was only a minor setback for land that has been rising for thousands of years as the great weight of the glaciers is dissolved by the suns warmth.