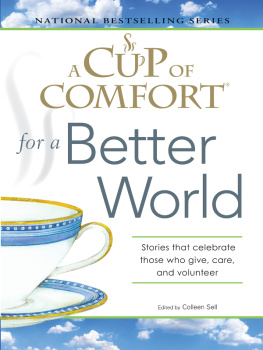

Ambiguity

Machines

&

Other

Stories

Vandana Singh

Small Beer Press

Easthampton, MA

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

Ambiguity Machines & Other Stories copyright 2018 by Vandana Singh (vandana-writes.com). All rights reserved.

Small Beer Press

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

smallbeerpress.com

weightlessbooks.com

info@smallbeerpress.com

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Singh, Vandana, author.

Title: Ambiguity machines : and other stories / Vandana Singh.

Description: Easthampton, MA : Small Beer Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017024759 (print) | LCCN 2017027227 (ebook) | ISBN

9781618731425 | ISBN 9781618731432 (softcover : acid-free paper)

Subjects: | BISAC: FICTION / Science Fiction / Short Stories.

Classification: LCC PR9499.4.S556 (ebook) | LCC PR9499.4.S556 A6 2018 (print)

| DDC 823/.92--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017024759

First edition 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Cover: Nebuleuse de la Lyre photograph by Paul Henry and Prosper Henry & Page from a Dispersed Book of Dreams (artist unknown) released into the public domain using the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) designation by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org).

Paper edition printed on 50# Natures 30% recycled paper by the Maple Press in York, PA .

For S.

je taime pour toujours

With Fate Conspire

I saw him in a dream, the dead man. He was dreaming too, and I couldnt tell if I was in his dream or he in mine. He was floating over a delta, watching a web of rivulets running this way and that, the whole stream rushing to a destination I couldnt see.

I woke up with the haunted feeling that I had been used to in my youth. I havent felt like that in a long time. The feeling of being possessed, inhabited, although lightly, as though a homeless person was sleeping in the courtyard of my consciousness. The dead man wasnt any trouble; he was just sharing the space in my mind, not really caring who I was. But this returning of my old ability, as unexpected as it was, startled me out of the apathy in which I had been living my life. I wanted to find him, this dead man.

I think it is because of the Machine that these old feelings are being resurrected. It takes up an entire room, although the only part of it I see is the thing that looks like a durbeen, a telescope. The Machine looks into the past, which is why Ive been thinking about my own girlhood. If I could spy on myself as I ran up and down the crowded streets and alleys of Park Circus! But the scientists who work the Machine tell me that the scope cant look into the recent past. They never tell me the why of anything, even when I askthey smile and say, Dont bother about things like that, Gargi-di! What you are doing is great, a great contribution. To my captorsthey think they are my benefactors but truly, they are my captorsto them, I am something very special, because of my ability with the scope; but because I am not like them, they dont really see me as I am. An illiterate woman, bred in the back streets and alleyways of Old Kolkata, of no more importance than a cockroachwhat saved me from being stamped out by the great, indifferent foot of the mighty is this... ability. The Machine gives sight to a select few, and it doesn t care if you are rich or poor, man or woman.

I wonder if they guess Im lying to them?

Theyve set the scope at a particular moment of history: the spring of 1856, and a particular place: Metiabruz in Kolkata. I am supposed to spy on an exiled ruler of that time, to see what he does every morning, out on the terrace, and to record what he says. He is a large, sad, weepy man. He is the Nawab of Awadh, ousted from his beloved home by the conquering British. He is a poet.

They tell me he wrote the song Babul Mora, which to me is the most interesting and important thing about him, because I learned that song as a girl. The song is about a woman leaving, looking back at her childhood home, and it makes me cry sometimeseven though my childhood wasnt idyllic. And yet there are things I remember, incongruous things like a great field of rice, and water gleaming between the new shoots, and a bagula, hunched and dignified like an old priest, standing knee-deep in water, waiting for fish. I remember the smell of the sea, many miles away, borne on the wind. My mother s village, Siridanga.

How I began to lie to my captors was sheer chance. There was something wrong with the Machine. I dont understand how it works, of course, but the scientists were having trouble setting the date. The girl called Nondini kept cursing and muttering about spacetime fuzziness. The fact that they could not look through the scope to verify what they were doing, not having the kind of brain suitable for it, meant that I had to keep looking to check whether they had got back to Wajid Ali Shah in the Kolkata of 1856.

Ill never forget when I first saw the woman. I knew it was the wrong place and time, but, instead of telling my captors, I kept quiet. She was looking up toward me (my viewpoint must have been near the ceiling). She was not young, but she was respectable, you could see that. A housewife squatting on her haunches in a big, old-fashioned kitchen, stacking dirty dishes. I dont know why she looked up for that moment but it struck me at once: the furtive expression on her face. A sensitive face, with beautiful eyes, a woman who, I could tell, was a warm-hearted motherly typeso why did she look like that, as though she had a dirty secret? The scope doesn t stay connected to the past for more than a few blinks of the eye, so that was all I had: a glimpse.

Nondini nudged me, asking, Gargi-di, is that the right place and time? Without thinking, I said yes.

That is how it begins: the story of my deception. That simple yes began the unraveling of everything.

T he institute is a great glass monstrosity that towers above the ground somewhere in New Parktown, which I am told is many miles south of Kolkata. Only the part were on is not flooded. All around my building are other such buildings, so that when I look out of the window I see only reflectionsof my building, and the others, and my own face, a small, dark oval. At first it drove me crazy, being trapped not only by the building but also by these tricks of light. And my captors were trapped too, but they seemed unmindful of the fact. They had grown accustomed. I resolved in my first week that I would not become accustomed. No, I didnt regret leaving behind my mean little life, with all its difficulties and constraints, but I was under no illusions. I had exchanged one prison for another.

In any life, I think, there are apparently unimportant moments that turn out to matter the most. For me as a girl it was those glimpses of my mothers village, poor as it was. I don t remember the bad things. I remember the sky, the view of paddy fields from my grandfathers hut on a hillock, and the tame pigeon who cooed and postured on a wooden post in the muddy little courtyard. I think it was here that I must have drawn my first real breath. There was an older cousin I dont recall very well, except as a voice, a guide through this exhilarating new world, where I realized that food grew on trees, that birds and animals had their own tongues, their languages, their stories. The world exploded into wonders during those brief visits. But always they were just small breaks in my life as one more poor child in the great city. Or so I thought. What I now think is that those moments gave me a taste for something Ive never hada kind of freedom, a soaring.