Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

My European Family by Karin Bojs

4th Rock from the Sun by Nicky Jenner

Patient H69 by Vanessa Potter

Catching Breath by Kathryn Lougheed

PIG/PORK by Pa Spry-Marqus

The Planet Factory by Elizabeth Tasker

Wonders Beyond Numbers by Johnny Ball

Immune by Catherine Carver

I, Mammal by Liam Drew

Reinventing the Wheel by Bronwen and Francis Percival

Making the Monster by Kathryn Harkup

Best Before by Nicola Temple

Catching Stardust by Natalie Starkey

Seeds of Science by Mark Lynas

Outnumbered by David Sumpter

Eye of the Shoal by Helen Scales

Nodding Off by Alice Gregory

The Science of Sin by Jack Lewis

The Edge of Memory by Patrick Nunn

Turned On by Kate Devlin

Borrowed Time by Sue Armstrong

Love, Factually by Laura Mucha

The Vinyl Frontier by Jonathan Scott

For Robin and Silvia, Isaac and Thomas

Contents

First, foremost and forever, I thank my wife Dr Patricia Brekke. Without her support, wisdom, patience, and occasional basic science tutelage, this book wouldnt have happened. From the whole of my heart, I thank you.

Thanks to my agent, Jenny Hewson at Rogers, Coleridge & White, for taking me on and giving me the self-belief and kick-up-the-arse I needed to get my book proposal into shape.

For helping this book grow from an idea into a distinct possibility with their time, input and advice, I would like to thank the superb science author Alanna Collen, Tim Reid at ClientEarth, and Carrie Plitt.

For taking a chance on a first-time author, and for their thoughtful, insightful editing, I owe huge thanks to Jim Martin and Anna MacDiarmid at Bloomsbury.

During the writing and research, I have too many people to thank to list them all if you are quoted in the book, I hope you will accept that as acknowledgement enough (lets face it, readers are more likely to see your name there than they are here!). But some special mentions: my brother-in-law Ewan Jones, for sending me newsletters, links, hastily taken photos of information posters, and his impeccably patient (and detailed!) maths and engineering explanations. To John Saffell at Alphasense for finding out what I was up to and giving me some valuable early steers. To my near-neighbour Neil Wallis, who made some very useful introductions, not least to his fathers brilliant book The New Battle of Britain . To transport guru Lukas Neckermann for infecting me with the electric and autonomous travel bug. And Suzanne Williams for the transcription services and (equally valuable) sense of humour.

To my hosts on my travels: in Delhi, Vandana and her father Vinod, for their kind hospitality and generous help during my stay. In Beijing, I cannot thank Manny Menendez enough for his time, guidance, and hugely entertaining company. In Paris, thanks to my good friend Annabelle Sappa (and cat) for the lodgings and bonhomie .

For help and support as the book deadline was getting agonisingly near yet so far, thanks to Hannah Gattrell. And, of course, to all my friends and family, who have had to put up with me droning on about this subject for the last two years and, now its published, for a little while longer, too

Finally, although I have already dedicated this book to my children and nephews (its obvious, really you are the future), I want to add another dedication at the end to two friends who passed away, much too young, whilst I was writing this book in the spring of 2018: Richard Silver and Ben Collen. You both continue to inspire.

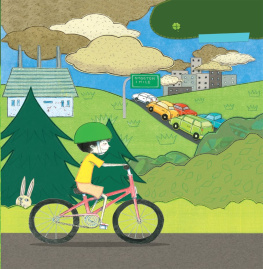

My first daughter was born in London in March 2014, at St Marys Hospital in Paddington, on the first day of spring. The sky was a brilliant blue and daffodils burst yellow with optimism from grey concrete pavement pots. I staggered out into the mid-morning to a new day, a new life, with all the hopefulness of fatherhood and new beginnings (and an urgent order for coffee to fulfil). But I was oblivious to the fact that I was walking down one of the most polluted roads in one of Europes most polluted cities. I also didnt know that we were in the middle of a month-long air pollution episode that would cause 600 deaths in London plus 1,570 emergency hospital admissions some at the very same hospital I had just emerged from.

In the coming weeks and months of that year, however, I started to become aware of air pollution. I hate myself for fitting the clich, but yes, parenthood did suddenly make me more aware of risk. The scene in the film Paddington where the Browns arrive at the maternity ward as carefree hippies on the back of a Harley-Davidson and leave nervously in a grey family car with their new arrival, rings embarrassingly true. As a sustainability journalist I had covered environmental issues for years for the Guardian , Financial Times , BBC and the Sunday Times . But I hadnt paid much attention to the most immediate environmental issue of all: the air we breathe. If I thought of air pollution at all, I thought of smog and smog was something other countries suffered from. But now, with an infant to protect, I started to notice the visceral throb of traffic in central London; the brown tinge to the sky even on cloudless days; the blackened nostrils after commuting on the Tube.

My awakening seemed to happen in parallel with that of other Londoners, too. Londons Mayor Boris Johnson confessed to the Evening Standard in December 2014 that Oxford Street had the worst diesel pollution on Earth. To say this came as a surprise is something of an understatement: the shopping street where I took my daughter to pick out her first pram had some of the most polluted air in the world ?! Where were the health warnings, the public information signs, the protesters marching? All I could see were happy, oblivious shoppers. Barely a week into 2015 came another Evening Standard headline: Oxford Street pollution levels breached EU annual limit just four days into 2015. The article said things about the EU limit for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels above 200 micrograms per cubic metre and something regarding tackling diesel pollution. But I had no idea what any of those things meant. What is nitrogen dioxide? Why is it bad? And whats the beef with diesel?

My professional instincts kicked in and I began to research. This started with a few articles, for the BBC and others, but soon the topic blew up. And not just in the UK, but in cities across the world. The smog in Beijing, China, was becoming so bad that it was dubbed the Airpocalypse. Pictures circulated on social media of Beijing students sitting their exams so couched in smog that they could barely see the neighbouring table. Stories emerged from Delhi, India, such as the Guardian s Toxic smog covers Delhi after Diwali (31 October, 2016), which pointed the finger at the density of some harmful particles and droplets in the air up to 42 times the safe limit. Particles of what, I wondered? Droplets of what? What safe limit? And then came the death figures. In late 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced that outdoor air pollution caused over 3 million deaths worldwide; by 2018, the WHO revised this up to 4.2 million.to the Royal College of Physicians, 40,000 people were dying each year from air-pollution-related illnesses. But what were these airborne illnesses?