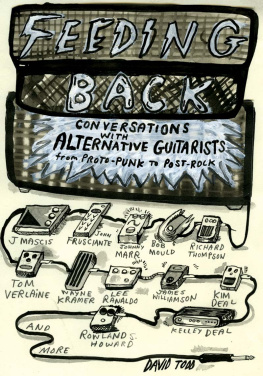

Copyright 2012 by David Todd

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-059-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feeding back : conversations with alternative guitarists from proto-punk to post-rock / [interviewed by] David Todd.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-059-0

1. GuitaristsInterviews. 2. Rock musiciansInterviews. I. Todd, David, 1971

ML399.C66 2012

787.871660922dc23

2012002144

Cover design: Jeffrey Scharf

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Question the heroic approach.

B RIAN E NO AND P ETER S CHMIDT

Take the only tree thats left and

stuff it up the hole in your culture.

L EONARD C OHEN

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

T HE Q UINE M ACHINE

Robert Quine was born in 1942 in Akron, Ohio, into a middle-class family and prospects of a straight life. He grew up on Link Wray and James Burton and played guitar eight hours a day, yet by the mid-1960s he found himself in a St. Louis law school just out of inertia. In 1969 he drifted farther west to San Francisco, but instead of the local strychnine, it was the death-meth of the Velvet Underground he sampled during their visits to town. When I first heard the V.U. I thought it was the worst, he told Perfect Sound Forever. Nonetheless, I became a total fanatic. After following the Velvets to New York City, he suffered there for years writing tax law and being received on the music scene very condescendingly. It wasnt until 1975 that he met a relative youngster named Richard Hell and fermented his strange mix of Albert Ayler, Chuck Berry, and the Stooges in a group called the Voidoids.

Robert Quine didnt look like a guitar herohe looked like a deranged Doonesbury characterand he didnt play like one. Quines fixed idea was brutality, his collaborator Jody Harris said in the oral history No Wave. But Quines was a particularly deep brand of negativism that encompassed the stranglebilly of the Voidoids Blank Generation and the severed nerves of Lou Reeds Waves of Fear and the noise-pop of Matthew Sweets Girlfriend, to name but a few of his excursions. If one premise of this book is that the alleged alternative rock guitar tradition can be encapsulated as what funnels into bands like the Stooges and then funnels out of bands such as Sonic Youth, Quine is at the center of the intervening pipeline. From my own selfish point of view, it was perfect for me, he said of the Voidoids early days at CBGB. I happened to have all these influences that were suddenly hip and fit into what was going on. By many peoples standards, my playing is very primitive, but by punk standards, Im a virtuoso. Thus Quine, as he was known even to his wife, was an anti-saint in a lineage that stretches from the neon Beat jazz of the Magic Band to the gothic punk of the Birthday Party, from the Krautrock of Neu! to the un-rock of Public Image Ltd. to the post-rock of Slint. Within the larger world we call alternative music, a more specific tradition runs back and forth among these groups and their guitar conceptualists, as evidenced by a series of connections inscribed in invisible ink. The point to this book is to shine a black light on their informal but vital exchange.

But what filters into the Stooges? Out of Sonic Youth? And what else does Quine have to do with that? With so many different ways of looking at the big picture, you just have to start by throwing a dart somewhere. The first lands on John Coltrane, just one notch away on this particular board from John Cale. Along with other free-jazz wildings such as Ayler and Archie Shepp, Coltrane and his counterpart Miles Davis represented music as a high sonic artthat is, a virtuosity not for its own sake but matched with ambitious ideas. As Miles famously put it, The difference between a fair musician and a good musician is that a good musician can play anything he thinks. The difference between a good musician and a great musician is what he thinks. These alternative guitarists saw free jazz as a figurative Carnegie Hall, but recognizing that they needed some other way to get there besides practice, they dug their own subway tunnels. I found that if I played my best Chuck Berry solo as fast as I could, with as much velocityif you just moved what he was doing over an inchit started to turn into those sheets of sound that Trane was playing, Wayne Kramer of the MC5 recalls herein. In true Warhol fashion, the art-punk guitarists probably did a better job on the frames than on the paintings themselves, but even with their shortcuts they achieved the dark magus potency of their heroes. Thats right, Iggy and the Stooges were every bit as good as Archie Shepp, Lester Bangs proclaimed in his 1979 article Free Jazz/Punk Rock. And John Coltrane could have played with the Velvet Underground.

The influence of the Velvet Underground on alternative music has been well documented, as has the impact of other seminal bands such as the New York Dolls. This book gathers plenty of the usual suspects, but another part of its goal is to pick up where previous treatments of alternative rock leave off. Looking at the Velvet Underground that way, one of their main contributions to these guitarists was the link they presented, via John Cale especially, to the minimalism of composers La Monte Young, Tony Conrad, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. Just as free jazz and wild punk converged as shared noise-on-sound, so did Reich and the Ramones meet at the vanishing point where all overtones become indistinguishableagain, respective training be damned. This fusion led to the work of direct descendants such as Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham (basically New Music with rock gear) and the next-level guys such as Sonic Youth (rock in just intonation), and even trickled down to Bob Mould (and his bag of dimes sound). Cale and Youngs Theatre of Eternal Music is perhaps the true prehistoric source for all of this music, by virtue of being the first ensemble to cross serious art with rock electrification. Also known as the Dream Syndicate, its low-flying-plane drones echoed through the guitar of the Stooges Ron Asheton, who rode them into his own shimmering trances. Different dronings leaked into this scene from the folk music of Davy Graham and the ragas of Ravi Shankar, just as different approaches to noise filtered in from improvisers Derek Bailey and Keith Rowe. Still, it made karmic sense that it was John Cale, sent by fate to produce the first Stooges album in 1969, who banged out the famous one-note piano line on their repetitive classic I Wanna Be Your Dog.

Cale also produced the debut album by the Patti Smith Group, whose guitarist Lenny Kaye assesses how songs such as I Wanna Be Your Dog differ from garage rock, the genre he codified with the 1972 anthology Nuggets. The garage aesthetic is another major strand in these guitarists DNA: the songs were fun to play and reproducible with cheap gear, and as a whole the movement composed a proto-DIY circuit to prefigure later undergrounds. Almost as important, Nuggets helped hold down the fort during a lull period within this lineage, that tenuous phase in the early 1970s when stadium shows and prog rock drowned out the Dolls in the United States and the Krautrock bands that were emerging in Germany. However, somewhere in there a shift took place, and the idea behind the Seeds Pushin Too Hard took a step punkward with the Stooges No Fun, one more step with the Patti Smith Groups own Rock n Roll Nigger. If the last cut on

Next page