Copyright 2007 by Kim Todd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

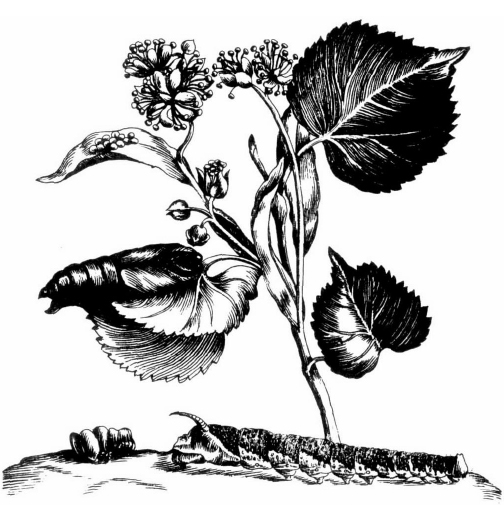

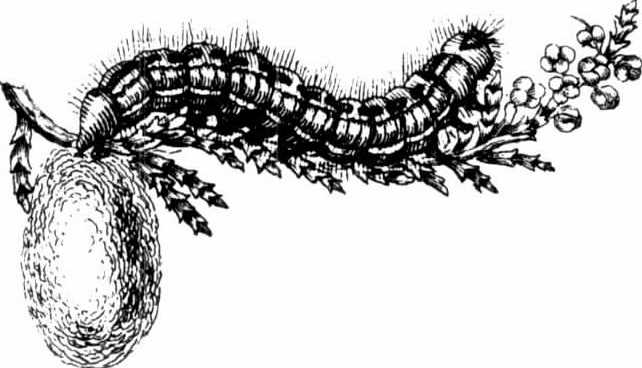

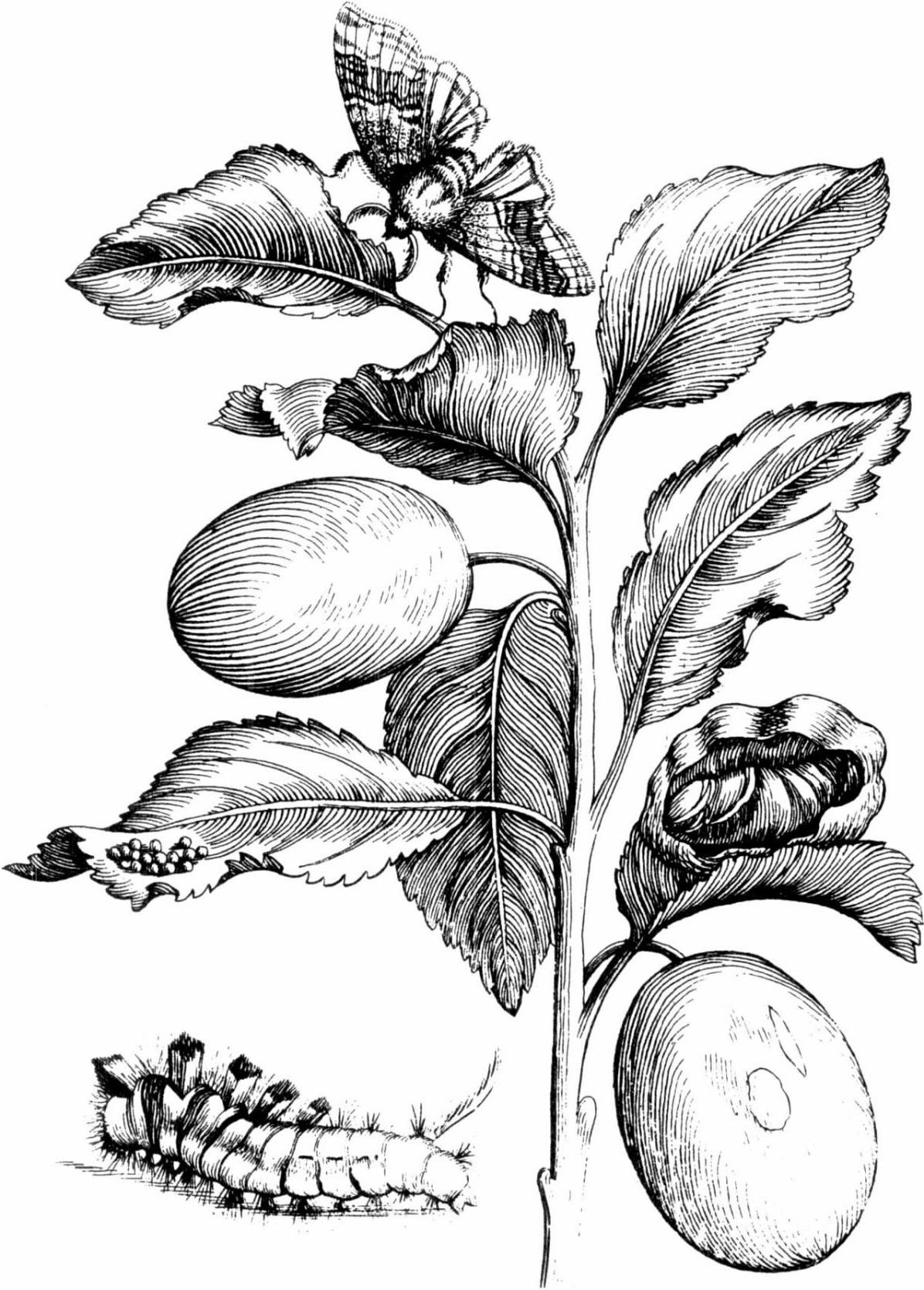

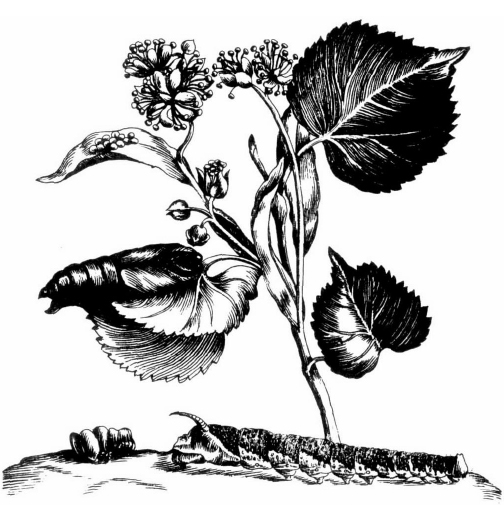

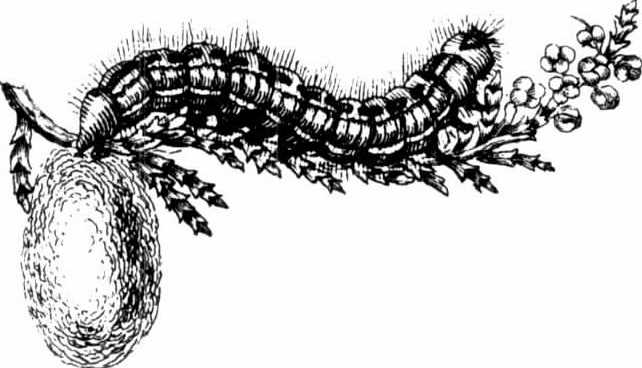

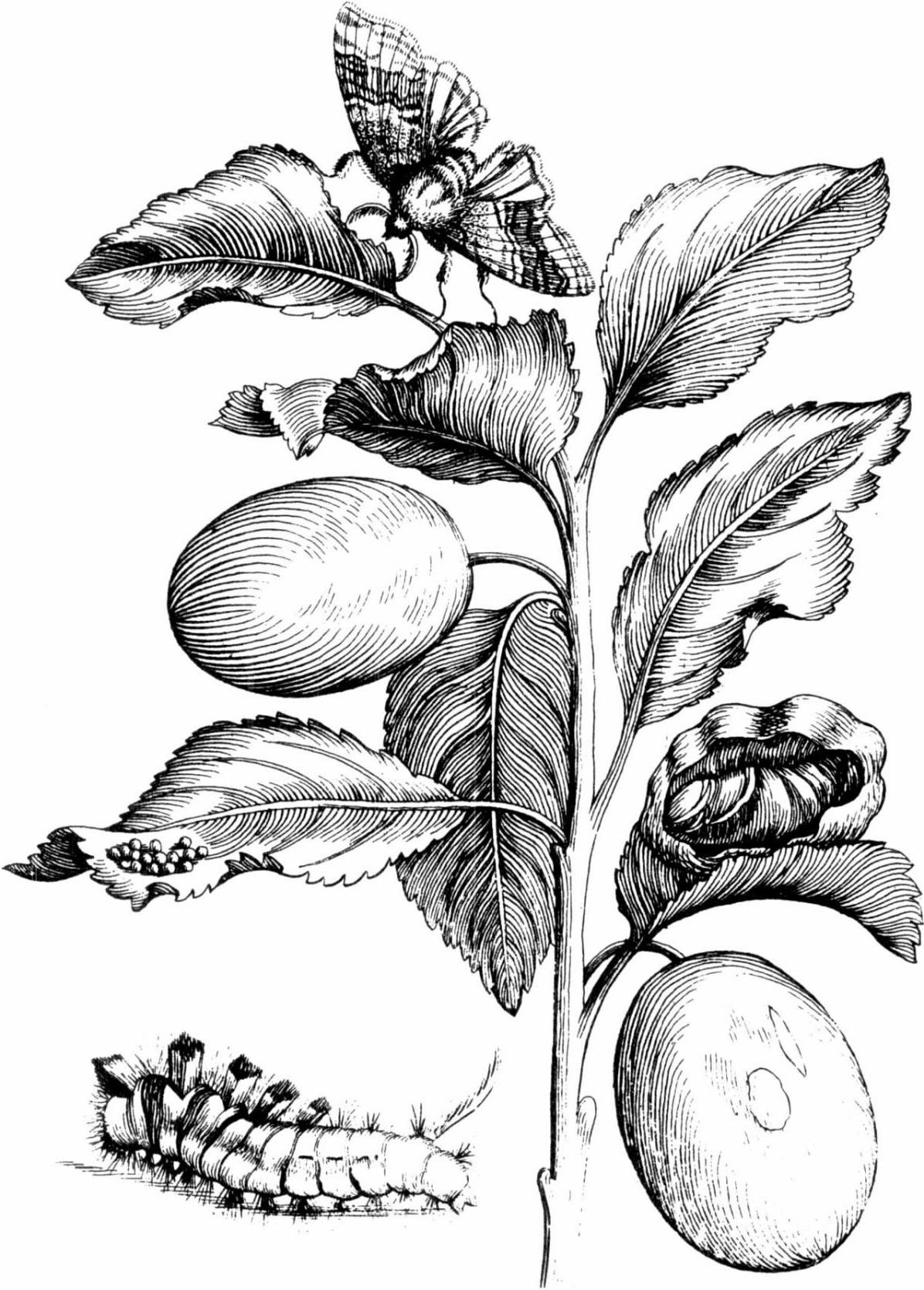

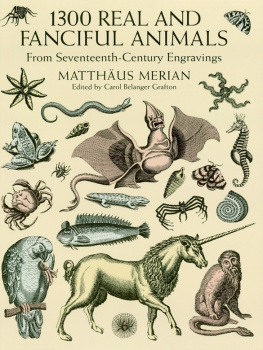

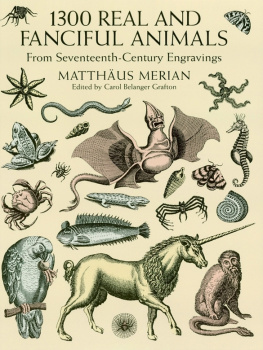

Illustrations are from Erucarum Ortus, Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis, a compilation of three of Maria Sibylla Merians books published in 1718 and are courtesy of Dover Publications.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Todd, Kim, 1970

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the secrets of

metamorphosis/Kim Todd.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Merian, Maria Sibylla, 16471717. 2. NaturalistsGermanyBiography. 3. ArtistsGermanyBiography. I. Title.

QH31.M4516T63 2007

508.092dc22 2006015367

[B]

ISBN 978-0-15-101108-7

ISBN 978-0-15-603299-5 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-0-547-53809-9

v1.0913

For Ben and Peregrine

For Ben and Peregrine

Prologue

Surinam, 1700

In the fields, cassava plants grew fiercely green, fed by the June rains that raked the plantation. Underground, their roots swelled with poison. When ripe, they would be grated, their juice extracted and boiled to leech out the toxins, their flesh baked into bread. Above ground, glossy leaves like seven-fingered hands soaked up the sun. The heat was unyielding, gripping temples and lungs like a meaty fist.

A small caterpillar with brown stripes inched along the plant, chewing its way across the leaf. Tufts of hair sprouted from each segment down its back. As the furry body carved a methodical, voracious path, a sharp-eyed woman stood in the field and watched its progress. She hadnt seen one like it before, that nut color, those stripes, and was curious what it would become.

She had traveled here to Surinam, this sugar-fueled Dutch colony in the South American rain forest, to document metamorphosis, the progression of change that revealed new talents, new aspects of personality, new body partsantennae, sexual organs, wings. She wanted to observe and paint each stage, capturing the shifts in color and form.

Not long before, she had been living in Amsterdam, peering at the dead butterflies in cedar-scented natural history cabinets of collectors. Conches, plump beetles, limp birds with eyes shuttered closed lay in the wood drawers, a background blank as a sheet of paper. She wanted to fill in that background, to see what plants the animals fed on, how they moved. Which caterpillar turned into each glossy moth? How long did it take from spinning a cocoon to hatching? How might the lives of these insects of New World forests be different from the ones she found in Old World flower beds?

Now, here she was, miles up this tropical river, far from the sophisticated streets of Europe, in a dangerous and undocumented place. Smells of boiling cane juice, swamp mud, and split guava replaced Amsterdams city air. Fevers paced the coast. Diseases plagued the entire country from dock to dense jungleleprosy, yaws, guinea worms, worms that crawled under the ankles, worms of the stomach and intestines, dry gripes, the bilious putrid fever of the West Indies. It was frightening to breathe.

The insects themselves were bold and untamable. They didnt respect human authority. Mosquitoes claimed stretches of forest and swamp by the ocean, forbidding trespassers with their dense swarms. Wasps circled her as she painted, building a mud nest nearby. Biting wood ants rained from the trees. When the mood struck, the ants swarmed through houses, carpeting the floor, papering the walls, leaving them shining and bare, ravaging any insect specimens she left unprotected.

In its box, her captive caterpillar consumed leaf after leaf, choosing flesh closest to the middle vein. Holes gaped in its wake. Then, one afternoon, it spun a silk button, disappeared into a pupa anchored to the silk, and dangled there like a small, unripe fruit. At this stage, she called them date pits. Like seeds, they were hard kernels of potential. Shed witnessed the transformation thousands of times, but each new pupa was wrapped in suspense.

Of all the shapes, wing patterns, color splotches, what will it become? Nothing as spectacular as the golden emperor moth, a hand span across, or the emerald-colored beetle with ruby-red eyes whose larva she found in her potato patch, surely, but a workable model. Maybe it was one of the small white-winged moths shed seen in fluttering clouds over the cassava crops.

Days passed without movement. Thunderstorms came and went, pelting the earth with heavy drops then rising up as steam. She worked on other projects, hunted other caterpillars, sketched and took notes, but kept her eye on the date pits. Often they broke open and pesky flies crawled out rather than the butterfly she waited for. That, or the pupa dried up and died, never moving to the next stage. Patience is a very beneficial little herb, she later wrote to a patron. Its an herb she cultivated.

She watched for the moment of hatching, ready to heat a darning needle, and, careful not to damage the wings, pierce the furry body. Some of her discoveriessnakes, iguanas, a geckocould be preserved in glass jars of brandy, but butterflies and moths were too delicate. They died quickly, still perfect. She placed them in a box and rubbed turpentine oil over the edges to ward off wood ants.

She painted her finds on leftover chips of parchmentlarva, pupa, adult with wings open, adult with wings closed, a quick sketch just to get down the details. She wielded her brush with a casual skill, knowing more about her insect subjects than perhaps any painter in Europe. Then she pasted them in the study book shed carried with her for years, creating a blue-paper frame, sticking it to the page with beeswax, and sliding the watercolor in. On the opposite page, she noted when and where she found the insects, recording how they behaved and what they ate.

This particular picture will be a strong addition to the book opening in her imagination. Shell capture all the colors of the cassava, from greens sliding toward brown to greens sliding toward blue, and the leaves will reach to every corner of the page. Close up, each cassava is a miniature jungle, and her rendering will draw the viewer into the thicket. Maybe to add interest, shell include an azure and black lizard, gripping the plants red stems. Its curling tail can fill out the bottom, tongue flicking at an ant on the stalk.

For the moment, though, the pupa ripened, turned transparent. Caterpillars rustled in the box. Her notebook was filled with blank pages. The plantation owner tallied up his harvest. They were all on the edge of change.

Before Darwin, before Humboldt, before Audubon, Maria Sibylla Merian sailed from Europe to the New World on a voyage of scientific discovery. An artist turned naturalist, Merian studied insects for most of her life. She started in the gardens and forests near her home in Germany, but in 1699, her fascination with the bizarre and stunning specimens carried from South America on trade ships pushed her farther. Over the course of two years, she stalked the sweltering rain forests of Surinam, flipping over leaves and peering down the throats of flowers, looking for the caterpillars that were her passion. Braving pounding heat, drenching rain storms, tarantulas and piranhas, with only her younger daughter for company, Merian searched out and sketched a record of her finds. Merian invested heavily in her experimental journey: she sold years worth of her paintings to pay for the trip, abandoned her husband, and rejected expectations of what a seventeenth-century woman should be and do.

Next page

For Ben and Peregrine

For Ben and Peregrine