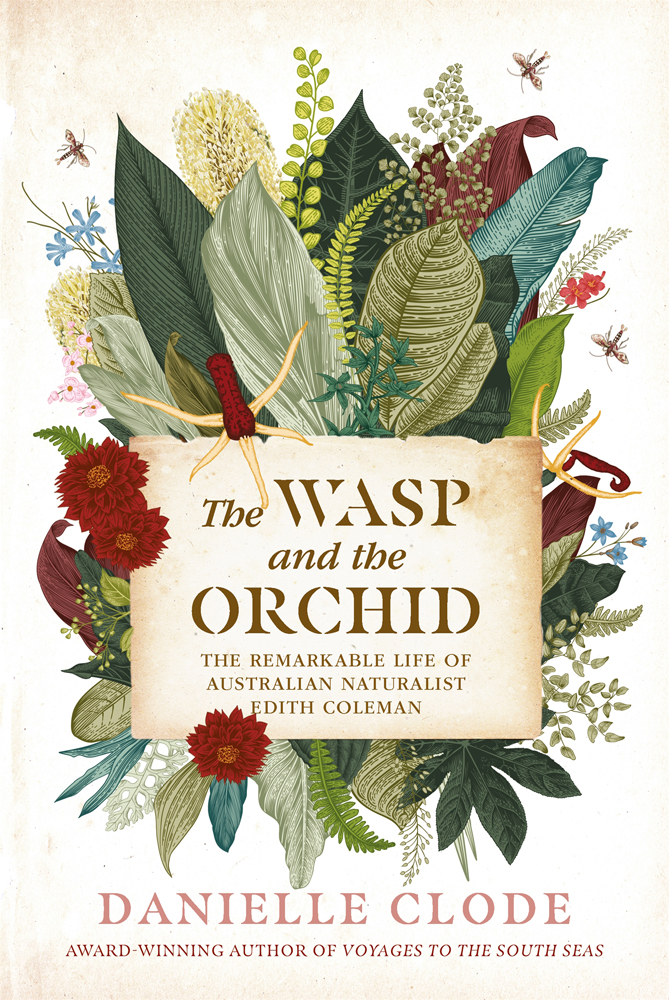

About The Wasp and the Orchid

Have you met Mrs Edith Coleman? If not you must I am sure you will like her shes just A1 and a splendid naturalist.

In 1922, a 48-year-old housewife from Blackburn delivered her first paper, on native Australian orchids, to the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria. Over the next thirty years, Edith Coleman would write over 300 articles on Australian nature for newspapers, magazines and scientific journals. She would solve the mystery of orchid pollination that had bewildered even Darwin, earn the acclaim of international scientists and, in 1949, become the first woman to be awarded the Australian Natural History Medallion. She was Australias greatest orchid expert, foremost of our women naturalists, a woman who needed no introduction.

And yet, today, Edith Coleman has faded into obscurity. How did this remarkable woman, with no training or connections, achieve so much so late in life? And why, over the intervening years, have her achievements and her writing been forgotten?

Zoologist and award-winning writer Danielle Clode sets out to uncover Ediths story, from her childhood in England to her unlikely success, sharing along the way Ediths lyrical and incisive writing and her uncompromising passion for Australian nature and landscape.

The WASP

and the

ORCHID

THE REMARKABLE LIFE OF

AUSTRALIAN NATURALIST

EDITH COLEMAN

DANIELLE CLODE

Contents

To my family for their support and inspiration: especially my grandparents and my parents but most of all to Mike, Lauren and Rachel

Extracts by Edith Coleman

Chapter 1

EDITH COLEMAN OF WALSHAM

If you love trim, tidy gardens in which roses grow as they are bid, my wilderness will make no appeal to you, for in it the roses long since took advantage of my pronounced dislike of the secateurs and wandered out of bounds. But if I lead them with a silken thread, as indeed I do, they reward my leniency with a wealth of colour and fragrance, and never were there sweeter roses than mine.

December 1942

The roses are still blooming at Walsham, tumbling down tangled brambles in floral abundance. Fragrance floats on the viscous hum of insect industry, distilling under the searing sun. Crackle-dry leaf litter collects in the curving paths that meander, creek-like, between islands of marigolds and foxgloves, herbs and delphiniums. The shady lace of gum leaves drifts overhead, barely veiling the cloudless sky.

The roses are still blooming at Walsham, tumbling down tangled brambles in floral abundance. Fragrance floats on the viscous hum of insect industry, distilling under the searing sun. Crackle-dry leaf litter collects in the curving paths that meander, creek-like, between islands of marigolds and foxgloves, herbs and delphiniums. The shady lace of gum leaves drifts overhead, barely veiling the cloudless sky.

For two young boys visiting their grandparents, the garden at Walsham is a wonderland. Few would realise what lies behind the impenetrable wall of pittosporum lining Blackburn Road. The plain paling fence, stained with Condys crystals and sump oil, reveals no secrets. But through the unassuming gate lies the loveliest garden you would ever see, a memory garden. A riot of perennials flourishes in every bed salvias and borage beloved of bees and spinebills. For John, the cottage garden is full of colour and scent always something in bloom with lots of insects visiting: fuchsias and petunias, hollyhocks and hydrangeas, wallflowers and roses. For other visitors there is a profusion of shrubs: the myrrh, the cinnamon, the calamus, the lavender, the thyme, the balsams and the other herbs.

The turtle pond is Peters favourite. A white-ringed eye rises, unblinking, from beneath the dark surface. Here and there, water bowls and feeding trays fill with the raucous fluff of feathers and beaks. Gleaming dark Australorps proudly declare the delivery of each egg from the poultry run out back. You could never be entirely sure what new creature you might find in their grandmothers garden. Resolute bees swarming in the apple tree have their city protected from rain by a groundsheet. Stickles and Prickles, the famed echidnas, and their various successors patrol the yard stretching along the southern fence. Museum jars and glassed boxes reveal mantids and grasshoppers. A section of closed-in verandah, occupied for years by the possums Bill Baillie and Mandy, now contains phasmids. A glass-fronted, two-storey Mansion House might hold two, twenty or two hundred pink-tailed white mice. Cheerful flocks of colour-bred budgerigars sing in the night rains from aviaries along the fence. Fat-tailed dunnarts might emerge from the pebbles in a small crate, or a hidden nest box covered in grass might reveal a sleeping blue-tongue lizard. Even spiders are warmly welcomed in this house.

To the north of the weatherboard bungalow, native eucalypts join the extensive fruit, herb and vegetable gardens that have taken over the tennis court where the boys mother and aunt once practised. The boys grandfather, James Coleman, empties the barrow of manure he is carting from the horse paddocks across the road into the big compost bins, adding to the piles of leaf litter and the mountains of clippings trimmed back from wayward plants. Their grandfather is usually found here, keeping their grandmothers garden under control tending, weeding, tidying and raking, when hes not playing bowls or tinkering in the shed. A barely raised hand and a tilt of the head acknowledge the boys arrival. Peter runs to join him in the orchard of apples, plums and figs.

Its an acre of paradise on the outskirts of Melbourne, just south of the train line to Healesville. The garden suburb of Blackburn is more rural than garden, more bush than park. Nonchalant gums lean over wood and wire fences, shading long quiet roads between haphazard houses scattered on quarter-acre blocks, horses and cattle grazing equably in between.

As John and his mother Gladys head for the back door, Auntie Dorfie emerges from her studio by the back fence, tinkling the silver bell on the doorpost as she passes.

Time for cake? she asks, always ready with a supply of sweet treats and entertainment for her nephews. As they step inside, Dorothy hurries down the hall to close the door of the Busyness Room. She puts one finger to her lips and smiles.

The boys grandmother, the famous Mrs Edith Coleman, is hard at work and must not be disturbed.

IN 1942, EDITH Coleman was at the height of her career. Internationally lauded as one of Australias leading naturalists, particularly in the study of orchids, Edith was a writer who needed no introduction. She wrote prolifically, not only for scientific journals, but also for newspapers and magazines. Her academic peers said her name ought to be Darwin and praised her insights into the mysteries of orchid pollination, which had left many before her, including Darwin, bemused.

England might have had its Gilbert White of Selborne, but Australia had its Edith Coleman of Walsham. Like White, Edith started her publication career late, at the age of 48. Like White, there is nothing in her past to indicate any particular talent or interest in nature or science. White was an English gentleman, with the usual pursuits of shooting and fishing, before he began his

The roses are still blooming at Walsham, tumbling down tangled brambles in floral abundance. Fragrance floats on the viscous hum of insect industry, distilling under the searing sun. Crackle-dry leaf litter collects in the curving paths that meander, creek-like, between islands of marigolds and foxgloves, herbs and delphiniums. The shady lace of gum leaves drifts overhead, barely veiling the cloudless sky.

The roses are still blooming at Walsham, tumbling down tangled brambles in floral abundance. Fragrance floats on the viscous hum of insect industry, distilling under the searing sun. Crackle-dry leaf litter collects in the curving paths that meander, creek-like, between islands of marigolds and foxgloves, herbs and delphiniums. The shady lace of gum leaves drifts overhead, barely veiling the cloudless sky.