Catherine Coleman Flowers - Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret

Here you can read online Catherine Coleman Flowers - Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: The New Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

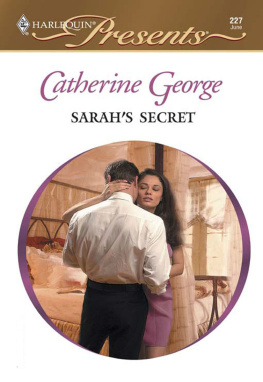

- Book:Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret

- Author:

- Publisher:The New Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

WASTE

WASTE

One Womans Fight Against Americas Dirty Secret

Catherine Coleman Flowers

Foreword by Bryan Stevenson

For Taylor, K.J., and seven generations to come

Contents

by Bryan Stevenson

Foreword

Our planet is dying. It is not a death from natural causes or some inevitable decline. Instead, we are slowly killing our future through greed, abuse of precious resources, reckless consumption, and irresponsible behavior. The environmental crisislike most criseswill victimize the poor and vulnerable the most. In the United States, Black people, indigenous people, and communities of color will bear the heaviest burden of avoidable disease, degraded quality of life, and unnecessary suffering. This has sadly become the American story.

For too long, the impact of environmental neglect on the poor and people of color has gone unaddressed, which is why the advocacy of people like Catherine Flowers is so important. Policymakers in our nation are painfully ignorant about the multiple ways low-income communities suffer from avoidable illness. Elected officials who believe we eradicated hookworm infections in the U.S. decades ago know nothing about what weve documented in Lowndes County, Alabama. Our policymakers have heard about asthma, lead poisoning, cancer, and a multitude of other sicknesses resulting from toxins, contaminants, and industrial waste, but there has been no appropriate response to the burden of these diseases on the poor. Our collective failure to invest in adequate sanitation, clean drinking water, and effective responses to pollution is taking life from the most vulnerable and marginalized among us.

In Alabamas rural Black Belt, the evidence of our neglect and exploitation of the poor can be seen everywhere. I met Catherine Flowers many years ago when impoverished Black residents in Lowndes County were being arrested and criminally prosecuted for not having functioning septic systemseven while being denied basic services and the infrastructure needed to install an effective system. Its a familiar dynamic Black people have endured since being forcibly trafficked to this continent from Africa. Policymakers create structural inequality and then criminalize those most burdened and at risk who fail to meet the demands of that structure.

The good news is that the work of Catherine Flowers demonstrates that there is more to this narrative. The children of the formerly enslaved in this region, the people terrorized by convict leasing and lynching, excluded by segregation and Jim Crow, dont just live in the rural Souththey persist with an unparalleled determination to survive and fight for equality and fair treatment. It is critical that we understand their stories if we are to save our planet.

I grew up in a poor, racially segregated rural community. Managing wastewater was a long-term challenge in our home. My brother and I spent years pumping raw sewage onto the same backyard where we played football and baseball. Flushing a toilet, taking a shower or a bath was perilous and came with unknown hazards for the household. Some of our neighbors relied on outhouses with no indoor plumbing to manage. As Ive grown older, I now realize that the worst part of these conditions is that we were made to believe that this is acceptablejust the way things arein the wealthiest nation in the world.

It is this orientation to environmental abuse, this accommodation of poverty and racially biased management of toxins and contaminants, that may be the most insidious aspect of our current crisis. Too many believe that we have no choice; this is the best we can do. Catherine Flowers tells an important story and reminds us that we do have a choice, we can do better.

Over the last thirty years, a movement has emerged to change the way we talk and think about environmental justice. Environmentalists have not always been as responsive to the perspective of the poor and the impact of environmental abuse on communities of color but through tireless advocacy and important work like the efforts detailed in this book, that is changing. There is a new chapter in the quest for environmental justice that is long overdue. Americas dirty secret is a secret no more and I pray that we all have the courage to act and to save the Earths most precious possession, its people.

Bryan Stevenson

WASTE

Chapter 1

My story starts in Lowndes County, Alabama, a place thats been called Bloody Lowndes because of its violent, racist history. Its part of Alabamas Black Belt, a broad swath of rich, dark soil worked and inhabited largely by poor Black people who, like me, are descendants of slaves. Our ancestors were ripped from their homes and brought here to pick the cotton that thrived in the fertile earth.

I grew up here, left to get an education, and followed a range of professional opportunities. But something about that soil gets in your blood. I came back with hopes of helping good, hard-working people rise up out of the poverty that bogs them down like Alabama mud. Little did I know that the soil itself would lead me to my lifes mission.

A big part of my work now is educating people about rural poverty and environmental injusticehow poor people are trapped in conditions no one else would put up with, both in Alabama and around the United States. Those conditionspolluted air, tainted water, untreated sewagemake people sick. They make it hard for children to thrive and adults to succeed. I tell people about the ways climate change is making those conditions even worse, and even more widespread, and that now theyre starting to afflict people who arent used to that kind of misery. I speak to audiences around the country and even abroad.

But when Im home in Alabama, I take people to see such conditions for themselves. We visit families crowded into rundown homes where no one should have to live, where people lack heat in the winter and plumbing in all seasons. We visit homes in the country with no means of wastewater treatment, because septic systems cost more than most people earn in a year and tend to fail anyway in the impervious clay soil. Families cope the best they can, mainly by jerry-rigging PVC pipe to drain sewage from houses and into cesspools outside. In other words, what goes into their toilets oozes outside into the woods or yards, where children and pets play. Pools of waste form breeding grounds for parasites and disease.

Moving to town isnt necessarily a solution. We meet families who pay for wastewater treatment in the towns where they live, only to have raw sewage back up into their homes, saturating rugs and carpets, whenever it rainsand it rains a lot in Alabama.

We see firsthand the conditions that led to a resurgence of hookworm, an energy-sapping tropical parasite that northern newspaper headlines called the germ of laziness in the early twentieth century when it was rampant in the South. It was considered eradicated by mid-century, when indoor plumbing was commonplace. Nobody gave it much thought until a few years ago. Thats when I convinced tropical disease experts to test Lowndes County residents for parasites, and they found that hookworm was back. That finding was ominous because Lowndes County isnt unique in its poverty or its geography. No one knows yet how far the hookworm infestation has spread.

Before I take anyone to Lowndes County, we start in nearby Montgomery, the state capital and one-time capital of the Confederacy, with a history lesson. Maybe its the former history teacher in me, but I believe that you cant understand how rural Alabama wound up with raw sewage in peoples yards without first learning about how African Americans were brought here as slaves to work the soil.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret»

Look at similar books to Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.