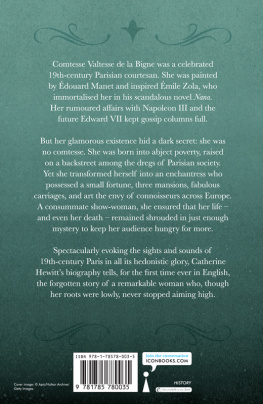

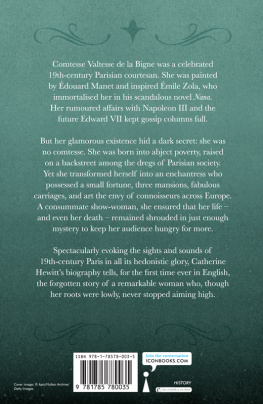

The Mistress of Paris

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Catherine Hewitt studied French Literature and Art History at Royal Holloway, University of London and the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her proposal for The Mistress of Paris was awarded the runner-ups prize in the 2012 Biographers Club Tony Lothian Competition for the best proposal by an uncommissioned, first-time biographer. She lives in a village in Surrey.

The Mistress of Paris

The 19th-Century Courtesan Who Built an Empire on a Secret

CATHERINE HEWITT

First published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd,

Bloomsbury House, 7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball,

Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road,

Woodstock 7925

ISBN: 978-184831-926-4 (hardback)

978-178578-003-5 (paperback)

Text copyright 2015 Catherine Hewitt

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Van Dijck by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Prologue

One Sunday afternoon in May 1933, journalist Jean Robert found himself in the northern French town of Caen. He had been invited to attend a lunch with some old school friends. Having spent several pleasant hours in their company, he hastened along to the town hall. The Annual Exhibition of Lower Normandy Artists was under way, and he was eager to see it before returning home. Once satisfied with his tour of the gallery, he stepped outside into the mid-afternoon sun. Checking his watch, Robert realised that he still had an hour before his bus left. As he pondered how best to use this time, his eyes alighted on a door just ahead of him. It was the entrance to the local museum. It had been left wide open, inviting. Delighted by the prospect of an absent-minded meander around the museum, the journalist hurried inside.

He climbed the stairs and entered the first room. But no sooner had his gaze begun its tour of the exhibition space than something peculiar caught his eye. It was a portrait of a well-to-do gentleman dressed in a blue, 18th-century costume. Robert recognised the name of the painter: douard Detaille. He was an artist Robert greatly admired. But Detaille was a painter of military scenes; this was not a soldier. As Robert stepped closer and read the inscription, he was taken aback: Etienne-Michel, Marquis de la Bigne. Then he noticed another painting by the same artist on display close by. This portrait showed an officer in Napoleonic uniform. The subject was identified as Sigismond-Tancrde, Comte de la Bigne. And both works, the journalist learned, had been bequeathed to the museum by a countess: Valtesse de la Bigne.

Robert was startled. He was friends with the current Marquis de la Bigne. Only a few years ago, he had assisted his friend in researching his familys history. He could not remember whether he had come across the names of these two men in the course of his research, but one thing was certain: he had never heard of this Valtesse.

How was this possible? De la Bigne was a local, noble name. Few people shared it. Those who did were almost certainly of the same family. How could he have missed the existence of a countess, and one who had died so recently? And how was it that these paintings had found their way into the museum in Caen?

As he left the museum, the strange name Valtesse ran through his mind. Who was this woman? He had to find out more.

Robert knew there to be some members of the de la Bigne family living in Paris, and he wasted no time in paying them a visit. Yes, they had heard about this woman. An adventuress, Robert was told. But the family could not provide him with anything more substantial. The journalists curiosity mounted.

Then, on his return home, something rather wonderful happened, quite by chance. Robert received a letter from a reader of the journal he wrote for. It told him about some research that was being done on Valtesse de la Bigne. Feeling it might be of interest, the author of the letter had included an article with his correspondence. Robert could hardly contain his excitement. He began to read. And as he did, an incredible story started to unfold.

This was no ordinary countess or art connoisseur. She had usurped the noble name, invented the men in the paintings, and then bequeathed them to the museum to cement a false association with local nobility. And more: this woman, though born into poverty and destitution, had risen to become one of the most powerful courtesans of 19th-century Paris.

Her tale begins with another young woman and a flight from Normandy to Paris in the tumultuous years of the 1840s.

CHAPTER 1

A Child of the Revolution

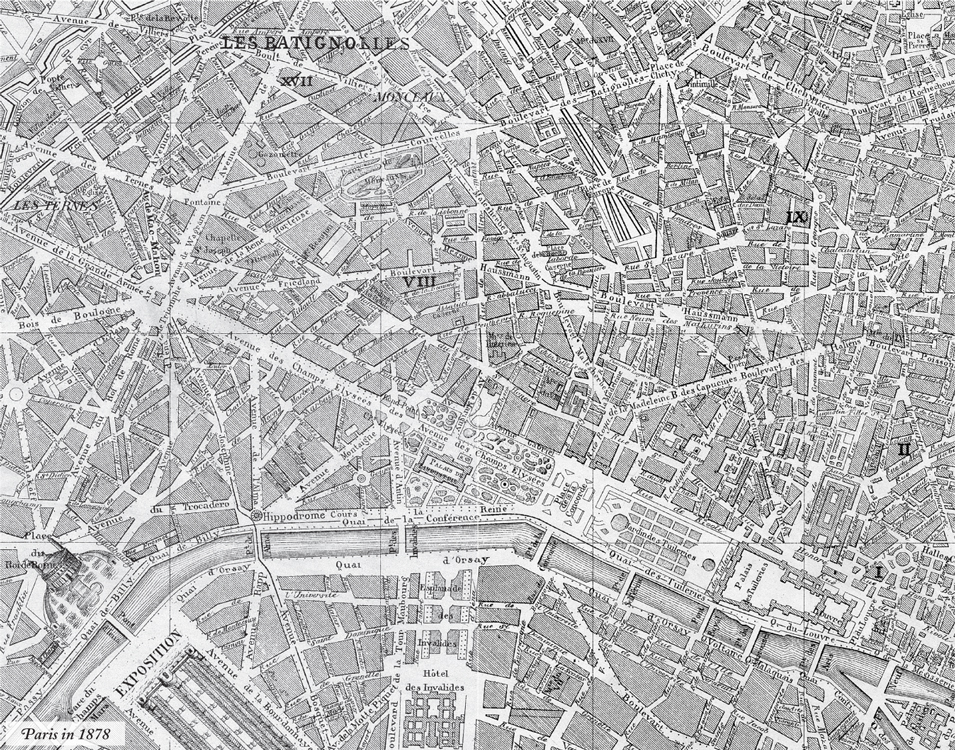

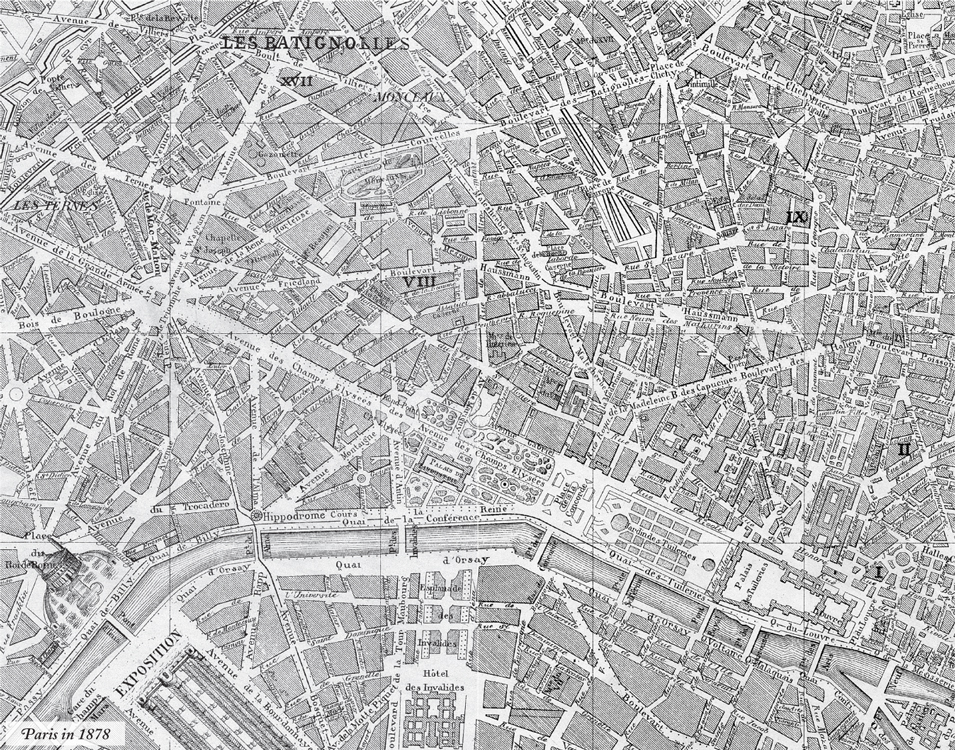

I t would still have been dark when the young peasant girl, Emilie Delabigne, boarded the diligence or stagecoach which was to carry her from Normandy to Paris early one morning in 1844. Having loaded a small bundle of possessions on to the roof, diligence passengers took their seats among the strangers who would become their travelling companions over the next three days. The coach must set off before sunrise if they were to maximise the daytime travelling hours diligences were not as costly as the faster mail coaches, but they would not drive through the night. Passengers were obliged to stop at one of the post stations dotted along the route to Paris where they would rest and eat. Eight people, sometimes more, could be packed into a diligence; at 24, Emilie might well have been the youngest woman of the party setting out that morning.

Country folk travelled to the capital for all sorts of reasons: perhaps some pressing business matter to attend to, or an illness in the family that would demand an extended stay with relatives. But it was too far for a humble peasant to travel simply for leisure. Emilie had a more serious reason for taking the coach to Paris.

Diligences were a notoriously uncomfortable mode of transport, particularly when the roads were rough, as they were in Normandy. Slowly, steadily, the vehicle would pick up pace, creaking as it went, Emilie had to steady herself to watch her childhood home gradually disappearing from view through the carriages tiny windows. It was a sight charged with poignancy, anticipation and trepidation. For at this moment, only one thing was certain: she was unlikely ever to see her home again.

Emilie was not the only young peasant moving to Paris at this time. Migration from country to city had always occurred, but the momentum increased from the mid-century as industrial and commercial development heightened the demand for labour. Paris dazzled and entranced, enticing the young with the promise of well-paid jobs, better standards of living, opportunities and adventure. By the middle of the 19th century, the mass departure of the young for the capital had become the bte noire of the regional press.

Next page