Contents

Guide

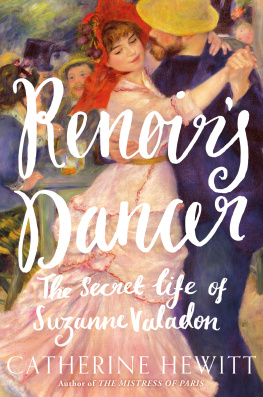

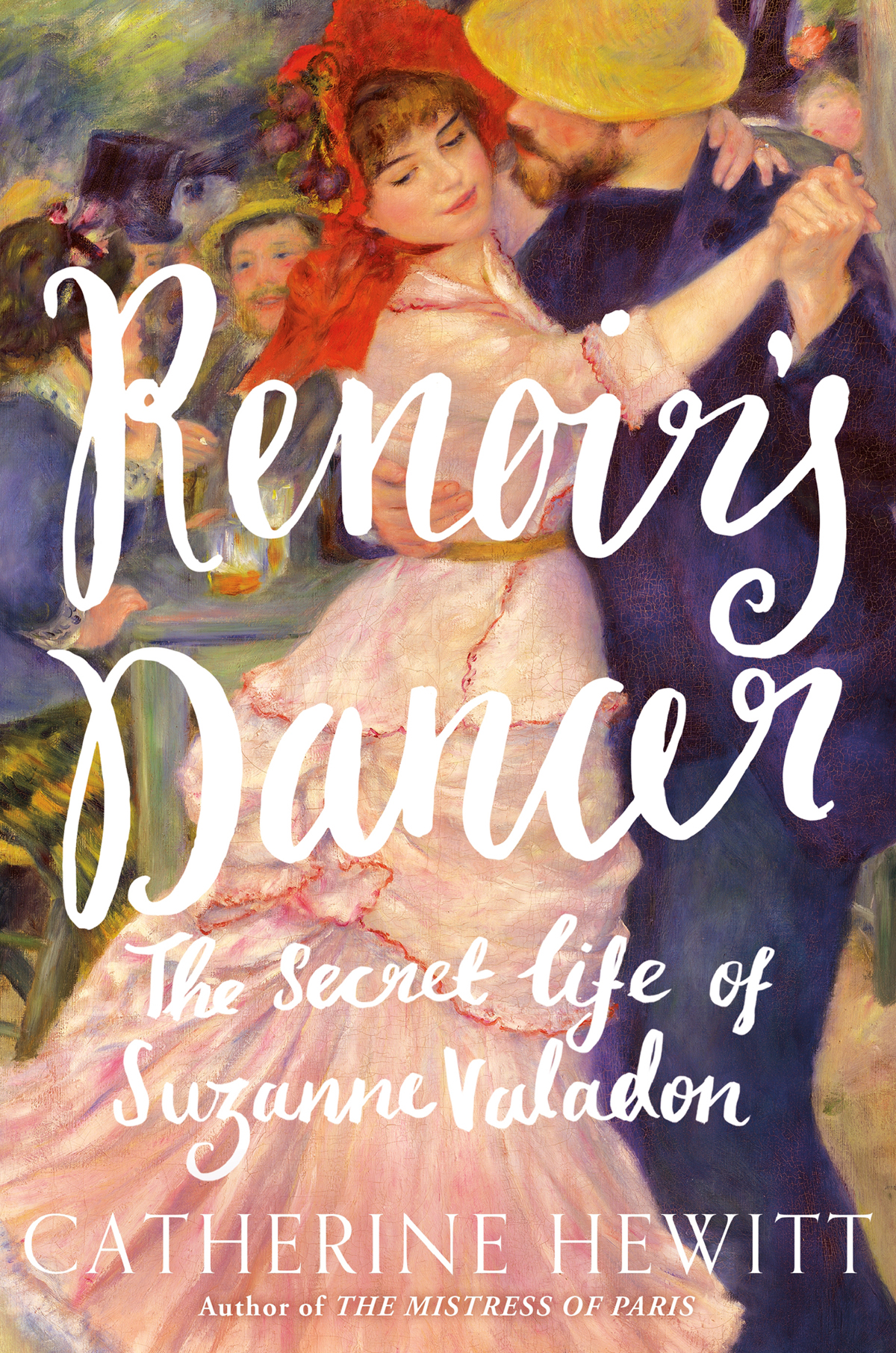

Renoirs

Dancer

The Secret Life of Suzanne Valadon

CATHERINE

HEWITT

St. Martins Press

New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FIGURES IN THE TEXT

The Place and Saint-Lger church in Bessines.

The former Auberge Guimbaud in Bessines.

Le Moulin de la Galette.

Young women in the Rue Cortot, c. 1900.

Suzanne Valadon, Paris, c. 1880.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, c. 1875.

Henry de Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1894.

Suzanne Valadon, Paris, 1885.

Edgar Degas in his library, 1895.

Suzanne Valadon, c. 1890.

Suzanne Valadon and Maurice Utrillo, c. 1890.

Suzanne Valadon, Paul Mousis and His Dog, 1891.

Suzanne Valadon, Nude Girl Sitting, 1894.

Suzanne Valadon and Maurice Utrillo, c. 1894.

Andr Utter.

Maurice Utrillo as a young man.

Andr Utter and Suzanne Valadon at her easel in the studio, c. 1919.

Suzanne Valadon painting.

Suzanne Valadon in 1925, her 60th year.

Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo and Andr Utter sharing a drink in the studio of the Avenue Junot, c. 1926.

Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo and Andr Utter, c. 1930.

Suzanne Valadon with her dogs at the property in the Avenue Junot, c. 19301.

Maurice Utrillo with his wife Lucie Valore.

COLOUR PLATES

When dawn broke on 2 October 1949, a thick mist had descended over the wooded valleys of the Limousin countryside, obscuring the little town of Bessines-sur-Gartempe and its 4,000 hectares of fields and hamlets. In the pastures, the warm russet of Limousin cattle appeared muted; from street level, chimneys and steeples were all but lost. Yet from the peaks of the surrounding granite hills, a milky autumn sun could be seen rising slowly against a cloudless sky. It promised to be a fine day.

The cobbled place at the heart of the town was still deserted. Not one of the surrounding buildings showed signs of life. The doors of the mairie were firmly bolted and not a soul entered the medieval church. Silence reigned.

But behind painted shutters, the people of Bessines were stirring. Already in the stillness, the sense of expectation was almost palpable.

Coloured bunting had been stretched across the streets, cheering the grey and beige stonework of the buildings as it flapped and fluttered in the gentle breeze. A short walk from the place, at a house especially brave in banderols, a section of 17th-century wall was concealed by a curtain. Nearby, a kind of platform had been erected, and several chairs covered in red velvet upholstery had been arranged on top. And right in the middle of this makeshift stage, there was a marvel to behold. The trickle of spectators who had now started arriving stopped to gaze in awe at the quintessence of modern innovations: there stood a microphone in dazzling metallic white paint. Many houses in Bessines still did not have running water.

The annual festival of Saint Lger, the towns patron saint, was always a great event. It was celebrated with all the enthusiasm generated by a year spent awaiting its arrival. When it came round, music, dancing and gaiety became the residents guiding principles for one glorious day. But this year, the people of Bessines were expecting a very important guest a famous guest. The whole town was poised in anticipation. The main road had been closed, the press had been alerted and someone even said that they had heard an American accent among the crowd. Bessines was a rural community which took altruism as its unspoken ethos and where hard work earned respect. The cult of celebrity was at once bewildering, wonderful and entirely out of the ordinary.

Before long, the men of the local band were arranging themselves in a corner by an arched doorway. With their top hats, trumpets and polished shoes, the group lent a sense of pomp and ceremony to the occasion. The testing of brass and the impromptu rehearsal of the drum signalled that it would not be long now. They were a jolly group, known as Les Gueules Sches or Dry Mouths an ironic choice, locals could not help observing, considering the guest they were about to receive.

The people of Bessines were now filling the streets in droves, and the band struck up a cheerful number to set the mood for the day. The crowd looked quite the part. Best shirts had been pressed, women had curled their hair; young boys had been made to scrub their knees and little girls permitted to wear frocks reserved for special occasions.

The school term had only just resumed, so the event was a welcome sweetener to a bitter pill. Young necks were craned in curiosity as children edged their way to the front of the crowd.

Let me tell you, one little girl solemnly informed the boy standing next to her, the plaque is under that curtain. Youll see soon enough. I know what it says by heart. My father fixed it in place.

Older spectators looked on with battle-weary eyes. The war was still chillingly fresh. Just a few miles away, the similar-sized town of Oradour-sur-Glane had found unsought fame when Nazi troops stormed in one Saturday afternoon and locked the towns women and children in the church and its men in the barns and outbuildings. Grenades and machine guns were turned on the men and the church set on fire. 642 people were massacred. That was just five years ago. For the townsfolk of Bessines, celebration still felt a surreal concept. They participated apologetically.

All at once, the church bell struck half past eleven. The ceremony commenced.

The light-hearted melodies ceased, and as the band shifted register, the crowd recognised the triumphant opening bars of La Marseillaise as a stirring call to patriotism. Older residents liked to boast that, at halfway between Paris and Toulouse, Bessines was at the centre of the world. Today, it really felt true.

Emotions ran high as an official-looking group stepped forward en masse. More cultured spectators could recognise notable personalities among them, including the local poet Jean Rebier and the painters M. Edmond Heuz and M. Rosier. There was the secretary of the Friends of the Municipal Museum of the Limoges, Robert Daudet, as well as some more familiar local faces such as M. Donquiert, the newly appointed sous-prfet of the nearby town of Bellac, and M. Duditlieu, Bessines own mayor. They made an impressive group. But one figure in particular held the peoples attention. All eyes were fixed on the man in the centre of the group, right at the front.

He was slim, in his mid-60s and visibly uneasy in his smart suit and tie. As the group advanced, he tottered slightly as he walked. An attempt had been made to tame his dark hair, but some unruly strands had escaped, giving him a wild appearance. A whole lifetime of suffering and experience was etched on his weathered face, while the creases of skin around his eyes told of a thousand dramas lived and emotions endured. His dark eyes darted about him rapidly, like those of a startled quarry. And when for a moment they came to settle on another person, his penetrating stare seemed to read their very soul. Never had a man looked so ill at ease before a crowd. And this was the celebrity everyone had come to see.