The Life and Times of Emile Zola

F.W.J. Hemmings

Contents

My first book on Zola, published in 1953 and completely revised for a later edition in 1966, was primarily a critical study of the works of the great French novelist. The present book represents the fulfilment of a long-standing ambition on my part to write a life of Zola, using all the relevant material that scholars from many countries have brought to light in the past twenty-five years or so. The two books have therefore different aims and should be regarded as separate though complementary.

All translations of Zolas writings used in this book are my own.

F.W.J.H.

Leicester, January 1977

The second half of the nineteenth century was a golden age for the fiction writer in France. Thanks to earlier reforms in the educational system made by Louis-Philippes energetic Prime Minister Guizot, a newly literate generation had come of age and was now avid for material to read. The era of prosperity ushered in by the upsurge of economic activity in the 1850s meant that the average French family had more money to spend on leisure pursuits and marginally more spare time to devote to them. The forms of mass entertainment familiar to us todaythe cinema, radio and television broadcasts, cheap travellay far in the future. Apart from occasional visits to the theatre or circus, the men and women of this earlier age were wholly dependent on the story-teller for that nurturing of the imaginative faculties that has always been felt as a fundamental requirement by ordinary people in every era and in all civilizations.

This was the age when Zola lived and launched himself on his extraordinarily successful career. Like Dickens in England a generation earlier, he spoke to a mass audience through the medium of the periodical press, the magazine or newspaper; the fact that their novels first appeared as serial stories may partly account for the keen sense, which both writers shared, of the immediacy of their reading public, all agog for the next instalment. Notes made by Zola before he started writing Germinal:the middle-class reader must experience a shudder of dread,such statements could almost have been made by Dickens when he sat down to compose Oliver Twist or The Mystery of Edwin Drood. The drab, uneventful, and repressed lives led by the great majority of the reading public in those days stimulated a demand for strong emotions and exciting action, safety sublimated in the imagined scenes of the world of fiction.

It was no mere coincidence that both Dickens and Zola started their literary careers as journalists; for this was also the age when the newspaper changed from being an expensive information sheet and forum for serious political discussion and began catering for the middle-brow reader who took a greater interest in the gossip column. The causeries and chroniques (amusing essays and short stories) that Zola was writing for the popular press in the late 1860s correspond closely, in manner and subject matter, to the Sketches by Boz that Dickens was contributing to the Evening Chronicle in the mid 1830s. Politically, too, both men could be described as anti-establishment progressives. When Zola first came up to Paris, in his late teens, the political atmosphere was stifling, and editors needed to keep a close watch on what was printed in their papers; for the authorities, who drew their support from the business and property-owning community, had no wish to see a recurrence of the social upheaval that had followed the 1848 Revolution. In the late 1860s, however, a more liberal policy was introduced, and the earlier strict political censorship was relaxed. This was the moment when Zola emerged as a satirical commentator on the events of the day. The kind of article he was signing in the last two years of the Second Empire shows that he already counted among the more radical members of the republican party. Simultaneously, he was planning the major creative undertaking with which his name is now chiefly associatedthe series of twenty interlinked novels entitled Les Rougon-Macquartand planning it as a documented exposure of the financial scandals and abuses of power with which the republicans of the period had for years been taxing Napoleon III and his ministers.

The Republic, so impatiently awaited, was proclaimed at a critical moment on 4 September 1870, the Emperor having abdicated after the humiliating defeat of his armies at Sedan. In spite of its shaky beginnings, the Third Republic endured for the rest of Zolas lifetime and indeed, outlasting the European war that followed, was to survive until a new German invasion dealt it its death-blow almost exactly seventy years after its painful birth. Few, however, would have been prepared to predict so long a spell of parliamentary rule when the Republic was set up in the middle of the disastrous war with Prussia. During the remaining three decades of the century, there were recurrent fears of a rightwing coup or else of a new revolution on the left, similar to but conceivably more successful than the attempt in 1871 to set up a working-class Commune in Paris.

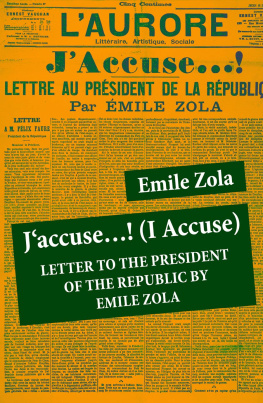

Absorbed by his literary work, Zola played no active part in the turbulent political life of the period, though the trend of certain of his novelsparticularly LAssommoir, Germinal, and the book he wrote about the Franco-Prussian War, La Dbcleshowed clearly enough where his sympathies lay. Only when he was close on his sixties, and universally recognized, if not revered, as the nations leading man of letters, did he suddenly decide to take a public stand on an issue which, though ostensibly turning on a suspected miscarriage of justice, had indisputable political implications. Zolas unexpected boldness in attempting to reopen the case of Captain Dreyfus, found formally guilty of military espionage and serving a life sentence in a penal colony overseas, was such as to place him at the focal point of world attention for months afterwards. His earlier, vaguely suspect reputation as the author of best-selling but somewhat unhallowed novels paled now before his new image as the lonely and courageous champion of a hapless victim of militarism and religious bigotry.

In his own country, this was not at all how Zola was seen except by an enlightened minority. His attack on the legality of the verdict passed on Dreyfus in 1894 aroused such a storm as had hardly been witnessed in France before. Zola was put on trial in his turna consequence he had foreseen and calmly discountedand was eventually compelled to seek asylum abroad. The forces arrayed against him were the same as he had attacked in his writings all his life: obscurantism, authoritarianism, religious and racial prejudice. Though no intellectual in the narrow sense, Zola cherished an invincible belief in the power of reason and in the need to consolidate the achievements of the Enlightenment; in many respects, indeed, he was a true heir of the encyclopdistes of the eighteenth century who had waged unremitting warfare against the Roman Catholic Church and had helped lay the ideological foundations of the French Revolution. His slogans were, it is true, different from theirs: not Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, but Truth and Justice; these two watchwords provided the titles for his last two novels, Vrit, which he wrote just before his death and which was published posthumously, and Justice, which he planned as its sequel but of which nothing has come down to us except the title itself and a few scrappy notes.