CULTURE AND SOCIETY IN FRANCE 1789-1848

F. W. J. HEMMINGS

Contents

The word culture is customarily used in a passive sense, as in phrases like a man of culture or in Matthew Arnolds celebrated but question-begging definition of culture as the acquainting of ourselves with the best that has been known or said in the world. For present purposes, however, it is the active sense that concerns us, in other words culture as meaning the production of works of art, of literature, or of music. And the first point to notice is that the products of cultural activity are not intended for consumption or application in the same way as are the products of human activity in other spheres. The artist is not a grower of crops nor an inventor of machinery. What he does could be called useless, since the things we call useful are always the things that can be put to use. The shepherd of today who whistles his dog is using a musical note for a specific purpose. The shepherd of the legendary pastoral age who played on his pipes was engaging in this activity for its own sake, and the air he played was a cultural product. A policemans or a referees whistle is utilitarian, a flute is not.

But the flute was invented, fashioned and perfected by men, and one must therefore suppose that it came into existence in response to a human need. The need for cultural stimulus and aesthetic satsfaction has been with us ever since the struggle to stay alive ceased to be so overwhelming that it absorbed all mans time and energy. From that point on, culture started to impinge on society, and vice versa; for it is one of the marks of a fully civilized society that the arts affect every activity, leaving their imprint on even purely utilitarian objects; the wine-jar is decorated, the sword is given a jewelled pommel; poetry, music and song turn mere mating into a congress of ravished spirits.

Strictly, the swordsman needs but a good smith to forge him a stout blade; in battle, the gold filigree work on the hilt might as well not be there. Because of the intrinsic uselessness of art, its practitioner always risks feeling himself to be, or even finding himself to be, an unassimilated outsider moving uneasily round the fringes of the society which supports him. In antiquity, and to some extent in medieval times, this fear of alienation was kept at bay by the religious significance that attached to cultural activities. Orpheus, the sweet singer, founded a sect of mystics; Apollo, a god, performed on the lyre and Athena, a goddess, was the patroness of the arts in ancient Greece. Later, Athena handed over to St Cecilia, and the cathedrals, providing unmatched opportunities for the gratuitous exercise of the architects gifts, were raised to the greater glory of God. Culture derives from cult, in more than just the etymological sense. Simply because original art is necessarily creation ex nihilo, it was always easy to link its practice with the mysteries of worship and ritual and to claim a divine source for its inventions. But as the centuries passed, religion loosened its hold over mens minds, and as society grew increasingly secularized, those who practised the arts had to find some other way to justify their activities. Support was found to be forthcoming, during the Renaissance and the post-Renaissance period, from the great monarchs, the powerful prelates and the wealthy noblemen of what were then the civilized countries of Europe. Greatness, power and wealth can best be displayed by the accumulation of apparently useless, but beautiful objects or by indulgence in apparently useless, but delightful activities. So the court painter and architect, the court poet and musician found a new role in supplying princes and popes with what they needed to testify to their magnificence.

This phase too came to an end, and the Revolution of 1789 in France, ushering in as it did a new age in which princely courts and aristocratic assemblies became an anachronism, and the accumulation of wealth and power a much more diffuse activity, posed two new problems for the purveyor of cultural artefacts. Who was he to work for? What purpose was his work to serve? In the absence of satisfactory answers to these questions, the danger of a new and disastrous alienation from society threatened to become acute.

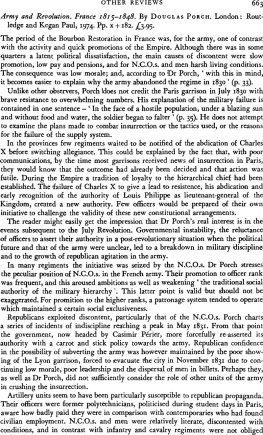

In fact, as this book and its sequel (already published) will try to show, this alienation did not manifest itself immediately, but only several decades later, after the revolution of July 1830 and increasingly and more acutely after the 1848 revolution. For the first ten years following the fall of the Bastille, the men who found themselves in control of the countrys destinies realized that, depending as they did in the last resort on the backing they had in public opinion, anyone who might help them direct and mould it could be very valuable to them. As the pictorial masterpieces of earlier times were transferred from inaccessible palaces to public museums, thus providing the rudiments for popular education in the fine arts, as authors grew accustomed to addressing themselves to every class of people instead of to a limited lite constituted by polite society, so those who specialized in creative cultural activity acquired a stronger influence than ever over broader areas of the national consciousness. A powerful political ruler like Napoleon regarded the painters, architects, dramatists and even musicians with a new respect, but also with a wary eye. Artists and writers found themselves liable to political persecution, a new and unpleasant experience but one which at least gave them a fuller understanding of the social role they might aspire to. After Napoleons fall, the part to be played in the society of the future by its culturally productive members was defined and codified by Saint-Simon and his followers.

In this way culture, over the period covered by this book, found itself caught up in a crossfire of encouragement and suspicion. Few artists had received more public honour than David; yet he was imprisoned after Thermidor and went into lifelong exile after the Restoration. Few writers - certainly no woman writer - had ever acquired the political influence wielded by Mme de Stal; but every copy of her most important book was seized and destroyed by the police of the First Empire. Throughout these 60 years the theatres and opera houses were crowded, as were the art galleries whenever an exhibition of contemporary painting was held. On the other hand, simply because culture was recognized to be so powerful a social force, crude methods of control such as the censorship were never more tyrannously applied.

But there were those who refused to commit brush or pen to any cause, preferring to stop their ears to the siren call of statesmen and religious leaders. Their talents, they thought, had been given them to be exercised for the benefit of all humanity; could it be right to devote time to the furtherance of this or that political programme? Was a social role compatible with the purity of their mission? Literature might be, as Bonald had said in 1806, the expression of society, but if that society was vulgar, materialistic, greedy and selfish, should not literature, should not art in general be on guard against contamination? This seems to have been the thinking behind a separatist, art for arts sake movement which emphasized the permanent and universal values of cultural activity and rejected the attempts of well-meaning philosophers to foist on it a dubiously useful social role. But however useless the artist may proclaim, proudly or humbly, his product to be, it needs an exceptional character to labour alone and ignored throughout his life, trusting in eventual posthumous recognition. Hence, in the absence of an immediate popular demand for certain innovative works of limited appeal, we shall find, before and immediately after 1830, the emergence of small groups or cnacles whose function it was to act as a self-contained association of producers and consumers isolated from, and by implication superior to the