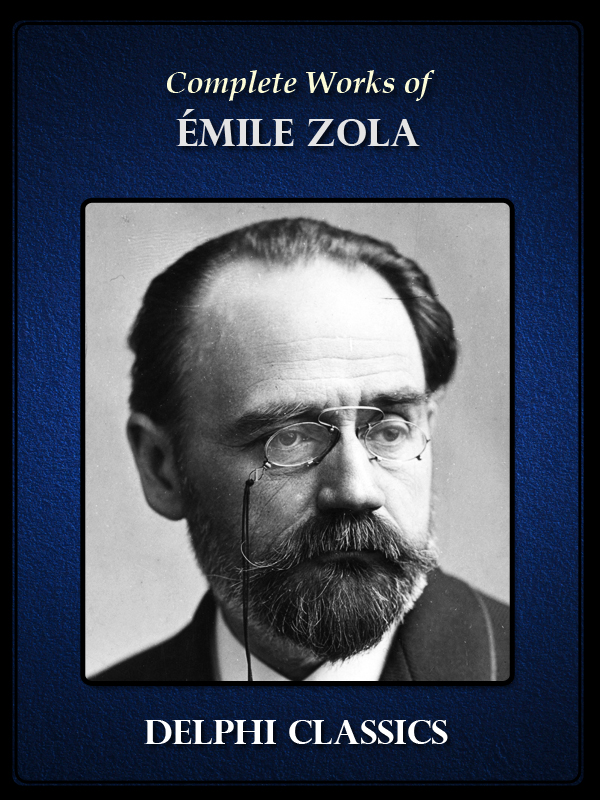

The Complete Works of

MILE ZOLA

(1840-1902)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2012

Version 1

The Complete Works of

MILE ZOLA

By Delphi Classics, 2012

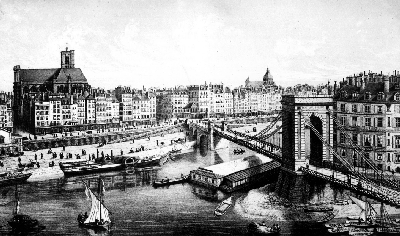

The Early Novels

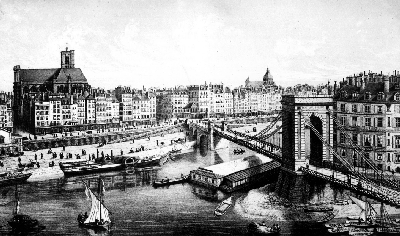

Paris in 1840, the time of Zolas birth

Rue St. Joseph, Paris Zolas birthplace

Zolas birth certificate

Zola with his parents

CLAUDES CONFESSION

Translated by John Sterling

In 1840 mile Zola was born in Paris to Franois Zola, an Italian engineer, and milie Aurlie Aubert, his French wife. The family moved to Aix-en-Provence in the southeast, when mile was three years old, but four years later Francois died, leaving Zolas mother to a meagre pension. The family was forced in 1858 to return to Paris, where Zolas childhood friend Paul Czanne, destined to become a world famous artist, soon joined him. Zolas mother had planned a law career for her son, but he failed his Baccalaurat examination and spent increasing time engaged in his writing. It was during this period of uncertainty that Zola started to write in a Romantic style, inspired by the works of Victor Hugo.

His interest in literature was most likely what influenced him in taking a position in the sales department of Hachette, which would become one of the countrys leading publishers. In time, Zola was to write literary and art reviews for newspapers, gaining in confidence in the literary environment he found himself working in. As a political journalist, Zola did not hide his dislike of Napoleon III, who had successfully run for the office of President under the constitution of the French Second Republic, only to misuse this position as a springboard for the coup dtat that made him Emperor.

In 1864 Zola wrote his first novel, La Confession de Claude, a semi-autobiographical work that attracted unwanted police attention, leading to Hachette agreeing with Zola that he should leave their employment. La Confession de Claude was Zolas first attempt at what he would later call an Experimental Novel. It was swiftly banned in the United States and Great Britain and was not translated into English for several decades. It tells the story of the young and idealistic Claudes relationship with a prostitute living in the same building as him.

Inside the Hachette publishing house, c. 1880

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XXIX.

DEDICATION.

To my Friends, P. Czanne and J. B. Baille.

You knew, my friends, the wretched youth whose letters I now publish. That youth is no more. He wished to become a man amid the wreck and oblivion of his early days.

I have long hesitated about giving the following pages to the public. I doubted my right to lay bare a body and a heart; I questioned myself, asking if it was allowable to divulge the secret of a confession. Then, when I re-read the panting and feverish letters, hanging together by a mere thread, I was discouraged; I said to myself that readers would, doubtless, accord but a cold reception to such a delirious and excited publication. Grief has but one cry: the work is an incessant complaint. I hesitated as a man and as a writer.

At last, I thought, one day, that our age has need of lessons and that I had, perhaps, in my hands, the means of curing a few wounded hearts. People wish poets and novelists to moralize. I knew not how to mount the pulpit, but I possessed the work of blood and tears of a poor soul I could, in my turn, instruct and console. Claudes avowals had the supreme precept of sobs, the high and pure moral of the fall and the redemption.

I then saw that these letters were such as they should be. I have no idea how the public will accept them, but I have faith in their frankness, even in their fury. They are human.

Hence, my friends, I resolved to publish this book. I took my decision in the name of truth and the general good. Besides, looking above the masses, I thought of you: it would please me to relate to you again the terrible story, which has already filled your eyes with tears.

This story is bare and true even to crudity. The delicate may not like it, but it will teach them a lesson they cannot fail to profit by. I have not felt at liberty to cut out a single line, being certain that these pages are the complete expression of a heart in which there was more light than darkness. They were written by a nervous and loving youth, who gave himself entirely to them amid the quivering of his flesh and the bounds of his soul. They are the morbid manifestation of a special temperament, which had a bitter need of the real and the false but sweet hopes of a dream. The whole book is a struggle between illusion and reality. If Claudes strange love-affair should make people judge him severely, they will pardon him at the dnouement, when he lifts himself up, younger and stronger, relying upon God.

There was an apostle in Claude. He tells us of his desolated youth, shows us his wounds and cries aloud what he has suffered that his brethren may avoid like sufferings. These are evil times for hearts which resemble his.

I can in a word characterize his work, accord him the highest praise that I desire as an artist, and, at the same time, reply to all the objections that may be made:

Claudes aspirations were too lofty.

MILE ZOLA.

CHAPTER I.

A MANSARDE IN THE LATIN QUARTER.

WINTER is here: the air in the morning becomes fresher, and Paris puts on her mantle of fog. This is the season of social soires. Chilly lips search for kisses; lovers, driven from the country, take refuge beneath the mansardes, and, huddling together before the hearth, enjoy, amid the noise of the rain, their eternal spring.

As for me, I live in sadness: I have the winter without the spring, without a sweetheart. My garret, away up a damp staircase, is large and irregular; the corners lose themselves in the gloom, the bare and slanting walls make of the chamber a sort of corridor which stretches out in the form of a bier. The wretched furniture, the narrow planks, ill fitted and painted a horrible red color, crack funereally when they are touched. Shreds of faded damask hang from the canopy of the bed, and the curtainless window opens upon a huge black wall, never changing and always repulsive.

Next page