Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Mom and Dad

Notes on Language

Because the issues Ive written about in this book are highly sensitive for Turks and Armenians, every choice Ive made is doomed to be a political act, even decisions on spelling. In my research, I have often lamented the frequency of error in the Turkish and Armenian media with regard to name spellings of members of the other ethnic group, and even as to whether a given name is male or female. Generally the mistakes are unintentional; but often they seem like evidence of a larger failure to engage, or to attempt to understand the other culture and take seriously its symbols. With this in mind, Ive chosen to spell all Turkish names with Turkish spellings and diacritical marks, even though this may seem cumbersome to an Anglophone reader.

GUIDE TO TURKISH PRONUNCIATION:

The Turkish language uses Latin characters, a handful of which take special diacritical marks. Approximate pronunciations are as follows:

c hard j sound, as in jar. Turkish example: Cemal, often spelled in English as Jemal.

ch sound, as in chicken. Turkish example: arpanak Island.

similar to w sound, but in practice nearly silent, such that Erdoan sounds like Erdowan or Erdo-an.

similar to the schwa vowel sound, as in the first syllable of again. Turkish example: the final syllable of Diyarbakr.

sh sound, as in share. Turkish example: Paa (Pasha in English).

ABOUT ARMENIAN TRANSLITERATIONS:

Armenian uses a distinct alphabet, so all transliterations of Armenian words into English are subject to debate. In some cases I have deliberately chosen to render a word in a specific dialect, or opted for the spelling most likely to be used by the group I am describing. For example, the word Hai, which means Armenian, is spelled as such in Camp Haiastan, but in the word Bolsahay I have kept the hay spelling typical in Turkish-Armenian usage. The most attentive Armenian-speaking readers will notice inconsistency in my rendering of the Armenian oo vowel sound. I have rendered it u in some cases and oo in others, depending on my own sense of how a given spelling will be interpreted by an English-speaking reader.

Contents

PART ONE

Diaspora

When We Talk About What Happened

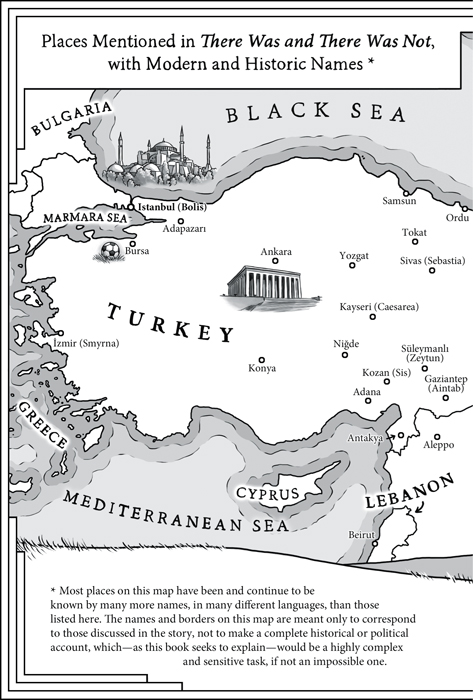

I had never, not for a moment, imagined Turkey as a physical place. Certainly not a beautiful place. But it was all I could do to get through my first taxi ride from the Istanbul airport into the citythe first of perhaps a hundred on that route, as I came and went and came back again and again over the span of four years before I was finishedwithout letting the driver see me cry. I shifted a bit so that my face would not be visible in the rearview mirror.

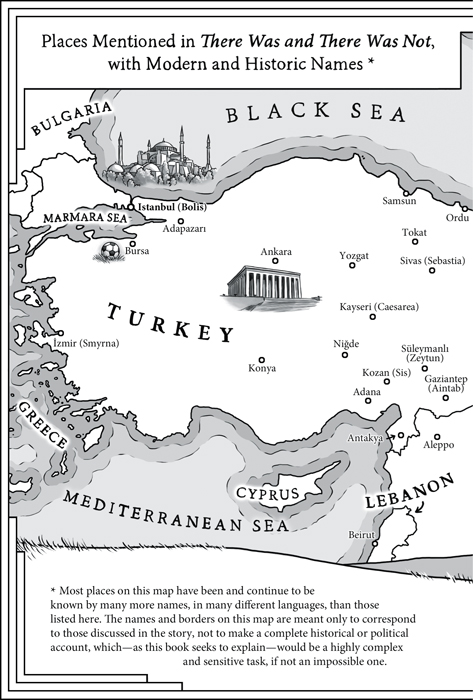

The sight of water was what did it. Istanbul is a city laced by three seas: the Marmara, the Bosphorus Strait, and the Black Sea. This struck me as utterly absurd. From as early as I knew anything, I had known Turkey only as an idea: a terrifying idea, a place filled with people I should despise. Somehow, through years of attending Armenian genocide commemorations and lectures about Turkeys denial of the genocide, of boycotting Turkish products, of attending an Armenian summer camp whose primary purpose seemed to be to indoctrinate me with the belief that I should fight to take back a fifth of the modern Turkish statesomehow in all of that, it never occurred to me to wonder what Istanbul, or the rest of Turkey, looked like. And here it was, a magnificent, sea-wrapped city, as indifferent to my imagination as I had been to its reality.

Was it anger I felt, something like what James Baldwin described when he recalled descending in a plane to the American South for the first time and seeing the stunning red hills of Georgia below him? This earth had acquired its color from the blood that dripped down from the trees, Baldwin wrote. I felt something like that, and the thought that now formed in a place I didnt know I still had within me was: how, after everything theyve done, do they get to have a place that looks like this?

No, thats not true. Anger was only what I was supposed to feel, what I perhaps even hoped to rekindle, when I arrived in Turkey, alone, looking out the window as the water chased the road all the way to my hotel. What I actually felt was loss. Not the loss of a place, of a physical homelandthat was for others to mourn. This had never been my homeland. The loss I felt was the loss of certainty, a soothing certainty of purpose that in childhood had girded me against lifes inevitable dissatisfactions; a certainty that as a college student and later as a journalist in New York City had started to fray, gradually and then drastically; a certainty whose fraying began to divide me uncomfortably from the group to which I belonged, from other Armenians. The embracing, liberating expanse of Istanbuls waters, and the bridges that crossed them, and the towers on hills that rose up and swept down in every direction, made me realize upon sight that I had spent years of emotional energy on something I had never seen or tried to understand.

This was 2005. I had come to Turkey that summer because I am Armenian and I could no longer live with the idea that I was supposed to hate, fear, and fight against an entire nation and people. I came because it had started to feel embarrassing to refuse the innocent suggestions of American friends to try a Turkish restaurant on the Upper East Side, or to bristle when someone returned from an adventurous Mediterranean vacation, to brood silently until the part about how much they loved Turkey was over. I came because being Armenian had come to feel like a choke hold, a call to conformity, and I could find no greater way to act against this and to claim a sense of myself as an individual than to come here, the last and most forbidden place.

Does it sound like Im exaggerating? Is there such a thing as nationalism that is not exaggerated?

* * *

W HEN WE TALK about what happened, there are very few stories that, once sifted through memory, research, philosophy, ideology, and politics, emerge unequivocal. But there are two things I know to be true.

One: I know that if your grandmother told you that she watched as her mother was raped and beheaded, you would feel something was yours to defend. What is that thing? Is it your grandmother you are defending? Is it the facts of what happened to her that you are defending, a page in an encyclopedia? Something as intangible as honor? Is it yourself that you are defending? If the story of the brutality that your grandmother encountered were denied or diminished in any way, you would feel certain basic facts of your selfhood extinguished. Your grandmother, who loved you and soothed you, your grandmother whose existence roots you in the world, fixes you somewhere in geography and history. Your grandmother feeds your imagination in a way that your mother and father do not. Imagination is farsighted; it needs distance to discern and define things. If somebody says no, what your grandmother suffered was not really quite as heinous as youre saying it is, they have said that your existence is not really so important. They have said nothing less than that you dont exist. This is a charge no human being can tolerate.