Contents

This World Is Small:

Prophecy and Reality in 1492

To Constitute Spain to the Service of God:

The Extinction of Islam in Western Europe

I Can See the Horsemen:

The Strivings of Islam in Africa

No Sight More Pitiable:

The Mediterranean World and the Redistribution of the Sephardim

Is God Angry with Us?:

Culture and Conflict in Italy

Toward the Land of Darkness:

Russia and the Eastern Marches of Christendom

That Sea of Blood:

Columbus and the Transatlantic Link

Among the Singing Willows:

China, Japan, and Korea

The Seas of Milk and Butter:

The Indian Ocean Rim

The Fourth World:

Indigenous Societies in the Atlantic and the Americas

The World Were In

This World Is Small

Prophecy and Reality in 1492

June 17: Martin Behaim is at work making a globe of

the world in Nuremberg.

I n 1491, a prophet appeared in Rome in rags, flourishing, as his greatest possession, a wooden cross. People thronged large squares to hear him announce that tears and tribulations would be their lot throughout the coming year. An Angelic Pope would then emerge and save the Church by abandoning worldly power for the power of prayer.1

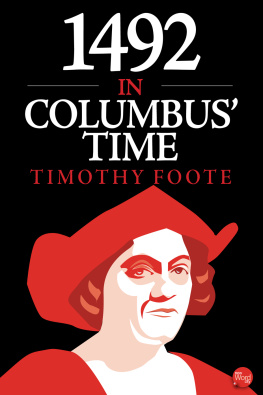

The prediction could not have been more wrong. There was a papal election in 1492, but it produced one of the most corrupt popes ever to have disgraced his see. Worldly power continued to mock spiritual prioritiesthough a ferocious conflict between the two began in the same year. The Church did not enter a new age but continued to invite and disappoint hopes of reform. The events the prophet failed to foresee were, in any case, far more momentous than those he predicted. The year 1492 did not just transform Christendom, but also refashioned the world.

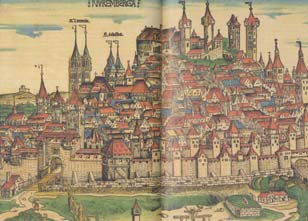

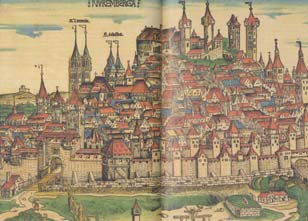

Late fifteenth-century humanists thought Nuremberg as significant as Athens or Rome. Illustrators of the world-overview, published there in 1493 at rich citizens expense, concurred.

Hartmann Schedel, Weltchronik [ The Nuremberg Chronicle ] (Nuremberg, 1493), engraving by Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydonwurff.

Until then, the world was divided among sundered cultures and divergent ecosystems. Divergence began perhaps about 150 million years ago, with the fracture of Pangaeathe planets single great landmass that poked above the surface of the oceans. The continents formed, and continental drift began. Continents and islands got ever farther apart. In each place, evolution followed a distinctive course. Every continent had its peculiar repertoire of plants and animals. Life-forms grew apart, even more spectacularly than the differences that grew between peoples, whose cultural variety multiplied, and whose appearance and behavior diverged so much that when they began to reestablish contact, they at first had difficulty recognizing each other as belonging to the same species or sharing the same moral community.

With extraordinary suddenness, in 1492 this long-standing pattern went into reverse. The aeons-old history of divergence virtually came to an end, and a new, convergent era of the history of the planet began. The world stumbled over the brink of an ecological revolution, and ever since, ecological exchanges have wiped out the most marked effects of 150 million years of evolutionary divergence. Today, the same life-forms occur, the same crops grow, the same species thrive, the same creatures collaborate and compete, and the same microorganisms live off them in similar climatic zones all over the planet.

Meanwhile, between formerly sundered peoples, renewed contacts have threaded the world together to the point where almost everyone on earth fits into a single web of contact, communication, contagion, and cultural exchange. Transoceanic migrations have swapped and swiveled human populations across the globe, while ecological exchange has transplanted other life-forms. Our own mutual divergence lasted for most of the previous one hundred thousand years, when our ancestors began to leave their East African homeland. As they adapted to new environments in newly colonized parts of the planet, they lost touch with each other, and lost even the capacity to recognize each other as fellow members of a single species, linked by common humanity. The cultures they created grew more and more unlike each other. Languages, religions, customs, and lifeways proliferated, and although a long period of overlapping divergence and contact preceded 1492, only then did a renewal of worldwide links become possible.

For seaborne routes of contact depend on the winds and currents, and until Columbus exposed the wind system of the Atlantic, the winds of the world were like a code that no one could crack. The northeast trades, which Columbus used to cross the Atlantic, lead almost to where the Brazil Current sweeps shipping southward into the path of the westerlies of the South Atlantic and on around the entire globe. Once navigators had detected the pattern, the exploration of the oceans was an irreversible processthough of course slow and long and interrupted by many frustrations. The process is now almost over. Uncontacted peoplerefugees, perhaps, from cultural convergencestill turn up from time to time in the depths of Amazonia, but now the process of reconvergence seems almost complete. We live in one world. We acknowledge all peoples as part of a single, worldwide moral community. The Dominican friar, Bartolom de Las Casas (14841566), who was, in effect, Columbuss literary executor, perceived the unity of humankind as a result of his experiences with indigenous people in a Caribbean island that Columbus colonized. All the peoples of the world, Las Casas wrote, in what has become one of the worlds most celebrated tautologies, are human, with common rights and freedoms.2

Because so much of the world we inhabit began then, 1492 seems an obviousand amazingly neglectedchoice, for a historian, of a single year of global history. Its commonest associations are with Columbuss discovery of a route to Americaa world-changing event if ever there was one. It put the Old World in touch with the New and united formerly sundered civilizations in conflict, commerce, contagion, and cultural exchange. It made genuinely global historya real world systempossible, in which events everywhere resonate together in an interconnected world, and in which the effects of thoughts and transactions cross oceans like the stirrings aroused by the flap of a butterflys wings. It initiated European long-range imperialism, which went on to recarve the world. It brought the Americas into the world of the West, multiplying the resources of Western civilization and making possible the eventual eclipse of long-hegemonic empires and economies in Asia.

By opening the Americas to Christian evangelization and European migration, the events of 1492 radically redrafted the map of world religions and shifted the distribution and balance of world civilizations. Christendom, formerly dwarfed by Islam, began to climb to rough parity, with periods of numerical and territorial superiority. Until 1492, it seemed unthinkable that the Westa few lands at the poor end of Eurasiacould rival China or India. Columbuss anxiety to find ways to reach those places was a tribute to their magnetism and the sense of the inferiority Europeans felt when they imagined them or read about them. But when Westerners got privileged access to an underexploited New World, the prospects altered. Initiativethe power of some groups of people to change othershad formerly been concentrated in Asia. Now it was accessible to interlopers from elsewhere. In the same year, unrelated events on the eastern edge of Christendom, where prophecy was even more heated about the imminent end of the world, elevated a new power, Russia, to the status of a great empire and a potential hegemon.