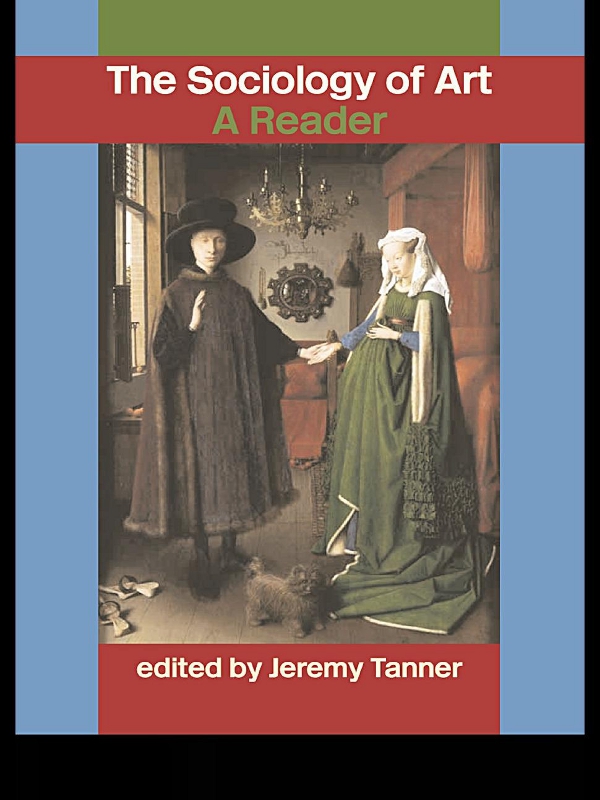

The book is divided into five parts exploring key themes in the sociology and social history of art:

With the addition of an introductory essay that not only contextualises the readings within the traditions of sociology and art history, but which also draws fascinating parallels between the origins and development of these two disciplines, this book opens up a productive interdisciplinary dialogue between sociology and art history as well as providing a comprehensive overview of the subject.

This book is essential reading both for students of the sociology of art and for students of art history.

First published 2003

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004.

2003 Jeremy Tanner for selection and editorial matter; the contributors and publishers for their chapters (as specified in the Acknowledgements)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

The sociology of art: a reader/edited by Jeremy Tanner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Art and society. 2. ArtSocial aspects. I. Tanner, Jeremy, 1963

N72.S6S62 2003

306.4'7dc21 2003001918

ISBN 0-203-63364-4 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-63698-8 (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0-415-30884-4 (hbk)

ISBN 0-415-30883-6 (pbk)

Preface

THIS READER IS DESIGNED to provide students with an introduction to the fundamental theoretical orientations which have characterised the sociology of art from its nineteenth-century origins, in Marxism, to contemporary contributions. Readings have been selected which are both representative of the major debates in the sociology of art and lend themselves most strongly to informing contemporary theoretical debates between art history and the sociology of art.

The introduction explores the development of both art history and sociology as new discourses which developed during the course of the nineteenth century in response to the development of modern social structures and cultural institutions. Consequently, many of the classics of sociological and art-historical thought for example Weber and Wlfflin have commonalities both in their intellectual background and in the kinds of intellectual problems in which they are interested: the relationship between collective structures and individual freedom, cultural evolution and the systematic character of processes of cultural change. In other cases, essays which are now recognised as classics in their own fields Panofskys essay on the methodology of iconographic and iconological interpretation and Karl Mannheims introduction to the interpretation of Weltanschauungen (worldviews) were originally written in response to each other, and are much better understood in relationship to each other than in the disciplinary isolation in which they are normally read today. My introduction goes on to explore some of the reasons why art history and sociology developed in separate directions during the course of the twentieth century, and some of the more recent attempts to cross the disciplinary divide, most notably in the sociology of art of Pierre Bourdieu and Michael Baxandalls critical art history.

The core of the Reader consists in five parts each exploring a key area in the sociology of art: the classic theoretical perspectives of Marx, Weber, Simmel and Durkheim; the social production of art; the sociology of the artist; sociological perspectives on high culture and museums; sociological approaches to style and aesthetic form. Each of the parts begins with a short introductory commentary. These commentaries discuss the main issues and approaches characteristic of the sociology of art in each of these areas, and in particular seek to characterise the distinctiveness of sociological from mainstream art-historical approaches, as well as pointing out areas where each discipline could benefit from deeper insight into and collaboration with the other. The intellectual background and key concepts of each of the selected readings are also introduced and explained in these introductory commentaries.

Any selection of readings in a particular academic discipline, whatever claims it may make to being representative of its field and I hope this Reader is representative is also programmatic. This volume is no different. It has two primary goals. First, intellectual excitement: it includes work by some of the finest sociological thinkers from the nineteenth century until today Marx, Weber, Durkheim, Simmel, Mannheim, Parsons, Elias, Habermas, Bourdieu all addressing problems which are crucial to our understanding of art: the social functions of high culture, the nature of artistic creativity, the relationship between social structure and aesthetic form. Second, interdisci-plinarity: the best art history is, implicitly at least, sociologically informed, and the best sociology of art places questions of artistic agency and aesthetic form at the core of its research. Consequently, a primary aim of this Reader is to make it easier for art history students to see the potential reward of exploring sociological perspectives on art in a more systematic way, and for sociologists to regain access to a critical tradition in art-historical and art-sociological thought which can allow them to address contemporary problems in the sometimes more nuanced, aesthetically informed manner characteristic of certain earlier strands of sociological thought.

Full bibliographical details have been given with each reading, for students wishing to return to the original source. Many of the original texts have been cut, and original notes and references omitted, where it was thought inessential to the main argument of the reading. Conventions of spelling and capitalisation, as also the use of language which might now seem unacceptably gender-biased, have been left unchanged.

Acknowledgements

Many friends and colleagues have contributed to this book in one way or another. In particular, I owe a great debt of gratitude to my teachers in both art history and sociology, especially Mary Beard, Harold Bershady, Robin Cormack, Victor Lidz, Robin Osborne and Anthony Snodgrass. Equally, this book would not have been written without the stimulus of my students in the Comparative Art MA programme at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Jas Elsner provided the proximate cause for this particular project, and I am profoundly indebted to him not only for his considerable help in bringing this work to fruition but for his intellectual companionship and many personal kindnesses over a number of years.