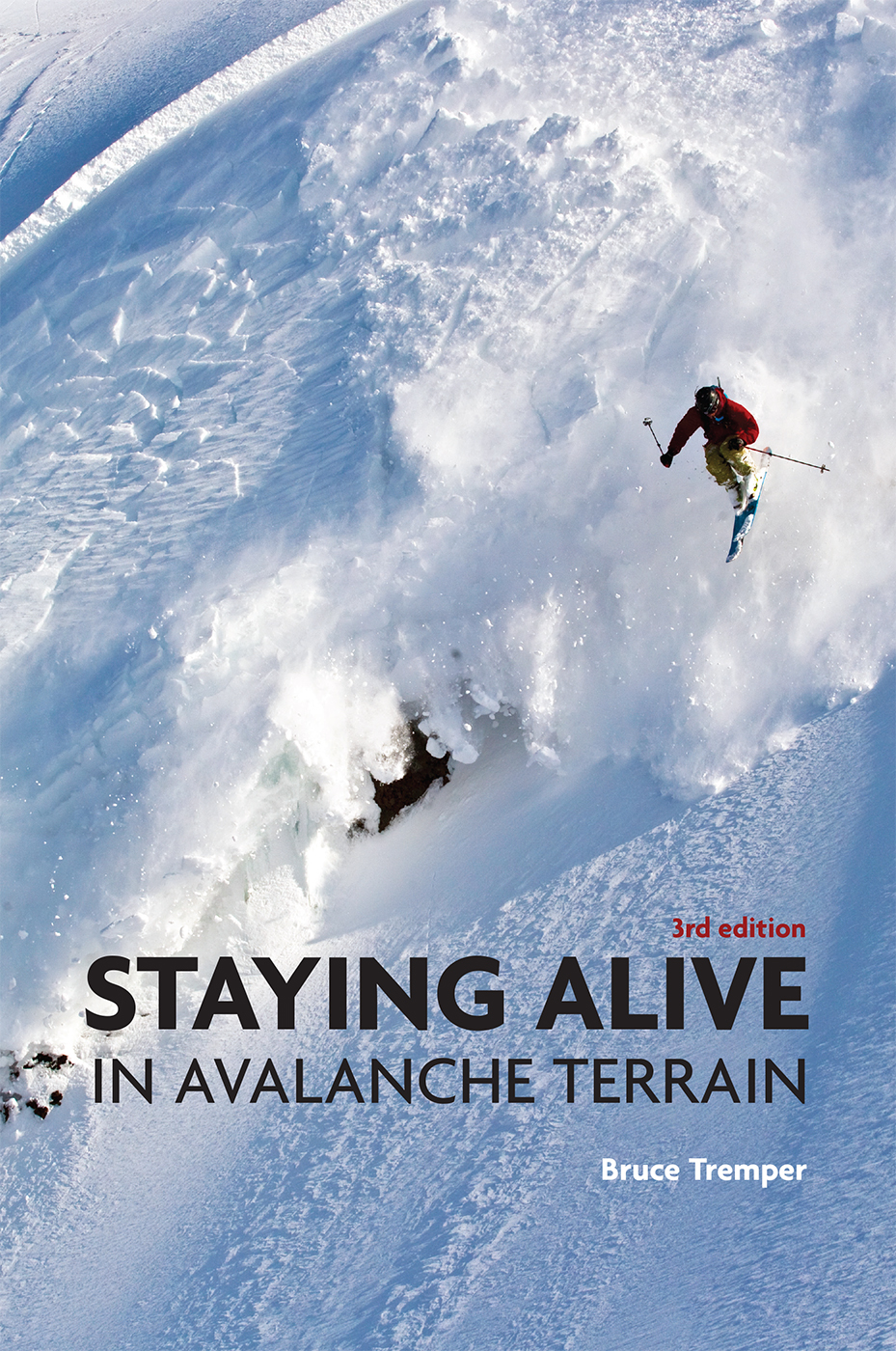

STAYING ALIVE

IN AVALANCHE TERRAIN

3rd edition

STAYING ALIVE

IN AVALANCHE TERRAIN

Bruce Tremper

MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS is the publishing division of The Mountaineers, an organization founded in 1906 and dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas.

1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98134

800-553-4453, www.mountaineersbooks.org

Copyright 2018 by Bruce Tremper

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed in the United Kingdom by Cordee, www.cordee.co.uk

First edition, 2001. Second edition, 2008. Third edition, 2018.

Copyeditor: Ginger Everhart

Design: Peggy Egerdahl

Additional design, layout, graphs, and charts: McKenzie Long, Cardinal Innovative

Illustrator: John McMullen

Cover photograph: Skier on Mount Baker in Washington (copyright by GrantGunderson.com)

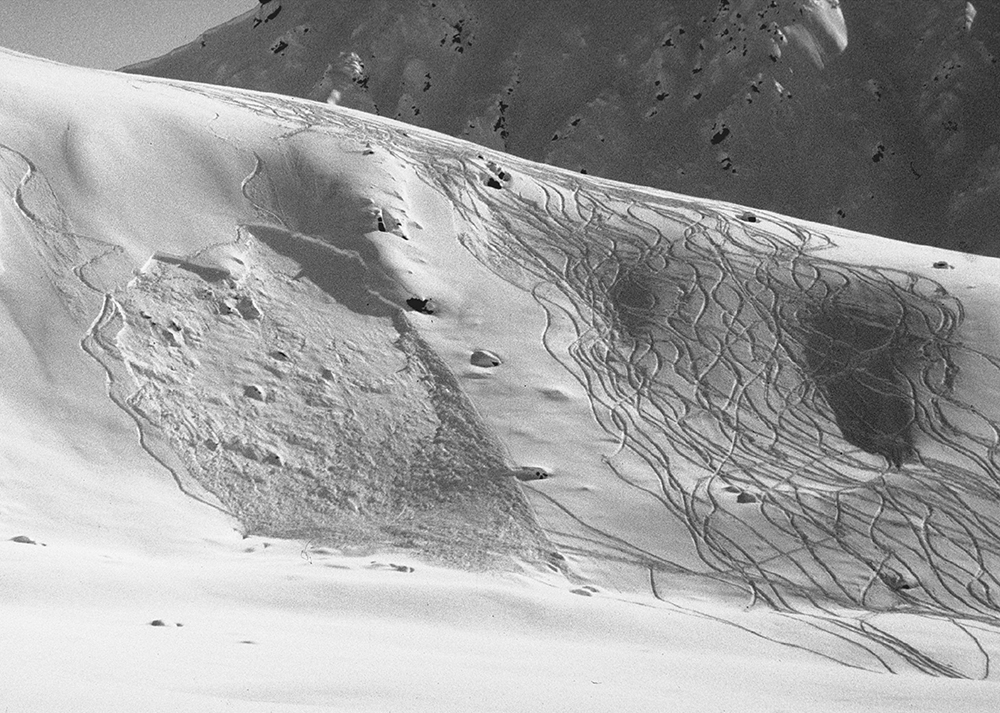

Frontispiece: This photo tells the story of a very close call, in this case, one with a happy ending that provided a cheap lesson.

All photos by the author in Wasatch Range, Utah, unless otherwise noted.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tremper, Bruce, 1953- author.

Title: Staying alive in avalanche terrain / Bruce Tremper.

Description: Third Edition. | Seattle, Washington : Mountaineers Books,

[2018] | First edition, 2001. Second edition, 2008. Third edition:

2018.T.p. verso. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020637| ISBN 9781680511383 (paperback) | ISBN 9781680511390 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: MountaineeringSafety measures. | AvalanchesSafety measures.

Classification: LCC GV200.18 .T74 2018 | DDC 796.9028/9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020637

Mountaineers Books titles may be purchased for corporate, educational, or other promotional sales, and our authors are available for a wide range of events. For information on special discounts or booking an author, contact our customer service at 800-553-4453 or .

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-68051-138-3

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-68051-139-0

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

When I first started dating Bruce twenty-five years ago, I thought, Cool! Now Ill get to ski all the steep and deep slopes before anyone else would dare ski them! The keys to the kingdom are mine! Boy was I wrong, at least in the way I had envisioned. Yeah, I got to ski some pretty great stuff, but not exactly with the razor-thin margin for error I had envisioned. What I learned pretty quickly about Bruce is that he is cautious. Scaredy-cat cautious. Slow, methodical, and deliberately cautious. Also, he very rarely skis in high-consequence terrain. What I learned pretty quickly about avalanche professionals in general is that they are cautious. Scaredy-cat cautious. Slow, methodical, and deliberately cautious. And they very rarely venture into high-consequence terrain.

They come by this honestly because, unfortunately, most avalanche professionals understand firsthand the heartbreaking consequences of accidents. Almost all have been in avalanches. Almost all have had friends die in avalanches. Many have dug out lifeless bodies. These tragic experiences have taught them the patience to wait until it is safe to have fun. Not just probably safesolidly safe. So, if you are reading this book to learn how to get the biggest adrenaline rush of your life and still survive, you might be better off watching some extreme videos instead. This book will almost certainly make you more cautious.

For the record, I dont have any regrets skiing with (and being married to) Bruce all these years. Even though we dont ski the kinds of slopes you see in those videos, I have learned that the true trick to skiing the backcountry is you can still have a blast in safe conditions and live to ski another fabulous day. And Ive had twenty-five years of doing just that. Thanks, Bruce!

Susi Hauser

INTRODUCTION

It is worth a reminder that there is nothing inherently safe about recreating on steep, avalanche-prone slopes.

Ian McCammon

It was November 1978. I was a cocky, ex-national-circuit ski racer, twenty-four years old, fresh out of college, and because I needed the money, I was building chairlifts at Bridger Bowl Ski Area in Montana. In the ignorance and vigor of youth, I naturally enough considered myself to be an avalanche expert. I had grown up in the mountains of western Montana, where my father had taught me about avalanches when I was ten years old, and I had been skiing in the backcountry the past several years and had so far avoided any serious mishaps. In other words, I was a typical avalanche victim.

I was skiing alone (first mistake) and not wearing a transceiver (second mistake). After all, I wasnt skiing, I was working, tightening the bolts at the base of each chairlift tower with a torque wrench. Even in my stubborn ignorance, I could see that it was clearly very dangerous. Over a foot of dense snow had fallen the night before, on top of fragile depth hoar, and the wind was blowing hard, loading up the steep slopes beneath the upper section of the chairlift with thick slabs of wind-drifted snow.

A skier-triggered, small, soft-slab avalanche in which the victim was uninjured. The victim or someone in the victims party triggers 93 percent of avalanche accidents, making avalanches the only natural hazard usually triggered by the victim. This is good news because it means we can prevent most avalanche fatalities by mastering avalanche and decision-making skills. (Talkeetna Mountains, Alaska)

Starting from the top, I skied down, stopping at each tower to torque the bolts. When I was finished with the tower at the top of the avalanche paths, I took off my skis and started walking back up the slope so I could gain the ridge and circle around to the tower beneath the avalanche paths. Then I quickly discovered my third mistake. Since I did not bring my backcountry skis or climbing skins, the easy climb was now an exhausting pig wallow back up through chest-deep snow, and the nearby snow-free cliffs were too scary to climb in my slippery plastic boots. I couldnt help but notice that only a thirty-foot-wide couloir at the base of the cliffs separated me from the safe slopes on the other side. Naturally enough, I thought a good skier like me should be able to get up speed and zip across it before anything too bad happened. Ski cutting alone and without a transceiver or partnerfourth mistake.

I did my ski cut according to the book. I built up speed and crossed the slope at about a 45-degree angle, so that, in theory, my momentum would carry me off the moving slab, in case it did break on me. Since I had never been caught in an avalanche before, I had no idea how quickly the slabafter it shatters like a pane of glasscan pick up speed. I heard a deep, muffled

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper