THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Urbina, Ian, author.

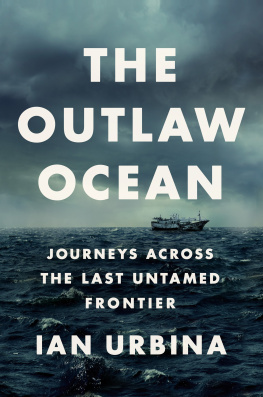

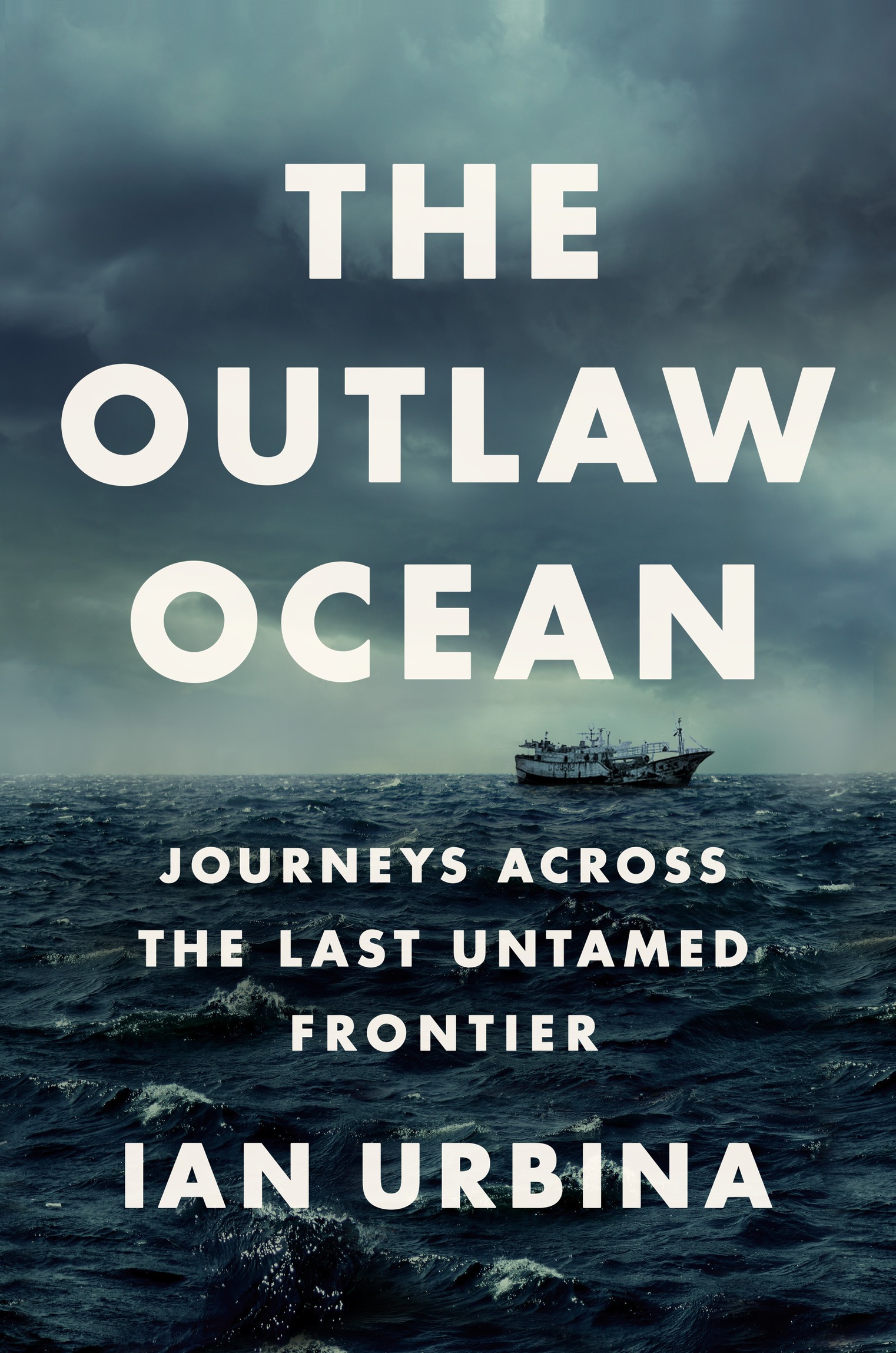

Title: The outlaw ocean : journeys across the last untamed frontier / by Ian Urbina.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001735 (print) | LCCN 2019011143 (ebook) | ISBN 9780451492951 (e-book) | ISBN 9780451492944 (hardback) | ISBN 9781524711641 (open market)

Subjects: LCSH: FisheriesCorrupt practices. | Law of the sea. | Oceania. | Ocean. | Urbina, IanTravel. | BISAC: TRAVEL / Special Interest / Adventure. | TRAVEL / Asia / General. | TRUE CRIME / General.

Classification: LCC SH319.A2 (ebook) | LCC SH319.A2 U73 2019 (print) | DDC 639.2dc23

Cover photographs: Palauan marine authorities approach the Taiwanese tuna long-liner called the Sheng Chi Huei 12 in Palauan waters by Benjamin Lowy / Getty Images; (background) Sadik Demiroz / Getty Images

For all its mayhem and exhaustion, there has been no greater adventure and no prouder project than being a part of your pit crew

INTRODUCTION

About a hundred miles off the coast of Thailand, three dozen Cambodian boys and men worked barefoot all day and into the night on the deck of a purse seiner fishing ship. Fifteen-foot swells climbed the sides of the ship, clipping the crew below the knees. Ocean spray and fish innards made the floor skating-rink slippery. Seesawing erratically from the rough seas and gale winds, the deck was an obstacle course of jagged tackle, spinning winches, and tall stacks of five-hundred-pound nets.

Rain or shine, shifts ran eighteen to twenty hours. At night, the crew cast their nets when the small silver fish they targetmostly jack mackerel and herringwere more reflective and easier to spot in darker waters. During the day, when the sun was high, temperatures topped a hundred degrees Fahrenheit, but they worked nonstop. Drinking water was tightly rationed. Most countertops were crawling with roaches. The toilet was a removable wooden floorboard on deck. At night, vermin cleaned the boys unwashed plates. The ships mangy dog barely lifted her head when the rats, which roamed on board like carefree city squirrels, ate from her bowl.

If they were not fishing, the crew sorted their catch and fixed their nets, which were prone to ripping. One boy, his shirt smudged with fish guts, proudly showed off his two missing fingers, severed by a net that had coiled around a spinning crank. Their hands, which virtually never fully dried, had open wounds, slit from fish scales and torn from the nets friction. The boys stitched closed the deeper cuts themselves. Infections were constant. Captains never lacked for amphetamines to help the crews work longer, but they rarely stocked antibiotics for infected wounds.

On boats like these, deckhands were often beaten for small transgressions, like fixing a torn net too slowly or mistakenly placing a mackerel into a bucket for sablefish or herring. Disobedience on these ships was less a misdemeanor than a capital offense. In 2009, the UN conducted a survey of about fifty Cambodian men and boys sold to Thai fishing boats. Of those interviewed by UN personnel, twenty-nine said they witnessed their captain or other officers kill a worker.

The boys and men who typically worked on these ships were invisible to the authorities because most were undocumented immigrants. Dispatched into the unknown, they were beyond where society could help them, usually on so-called ghost shipsunregistered vessels that the Thai government had no ability to track. They usually did not speak the language of their Thai captains, did not know how to swim, and, being from inland villages, had never seen the sea before this encounter with it.

Virtually all of the crew had a debt to clear, part of their indentured servitude, a travel now, pay later labor system that requires working to pay off money they often had to borrow to sneak illegally into a new country. One of the Cambodian boys approached me, and deeper into our conversation he tried to explain in broken English how elusive this debt became once they left land. Pointing to his own shadow and moving around as if he were trying to grab it, he said, Cant catch.

This was a brutal place, one that I spent five weeks in the winter of 2014 trying to visit. Fishing boats on the South China Sea, especially in the Thai fleet, had for years been notorious for using so-called sea slaves, mostly migrants forced offshore by debt or duress. The worst among these ships were the long haulers, many of which fished hundreds of miles from shore, staying at sea sometimes for over a year as mother ships provided supplies and shuttled their catch back to shore. No captain had been willing to carry me and a photographer the full distance, more than a hundred miles, out to these long-haul boats. So, we instead hopscotched from boat to boatforty miles on one, forty on the next, and so onto get out far enough.

As I watched the Cambodians, who, like some water-bound chain gang, chanted to ensure synchronicity in pulling their nets, I was reminded of an incongruity that confronted me time and again over several years of reporting offshore. For all its breathtaking beauty, the ocean is also a dystopian place, home to dark inhumanities. The rule of lawoften so solid on land, bolstered and clarified by centuries of careful wordsmithing, hard-fought jurisdictional lines, and robust enforcement regimesis fluid at sea, if its to be found at all.

There were other contradictions. At a time when we know exponentially more about the world around us, with so much at our fingertips and but a swipe or a tap away, we know shockingly little about the sea. Fully half of the worlds peoples now live within a hundred miles of the ocean, and merchant ships haul about 90 percent of the worlds goods. Over 56 million people globally work at sea on fishing boats and another 1.6 million on freighters, tankers, and other types of merchant vessels. And yet journalism about this realm is a rarity, save for the occasional story about Somali pirates or massive oil spills. For most of us, the sea is simply a place we fly over, a broad canvas of darker and lighter blues. Though it can seem vast and all-powerful, it is vulnerable and fragile in part because environmental threats travel far, transcending the arbitrary borders that mapmakers have applied to the oceans over the centuries.

Like a dissonant chorus in the background, these paradoxes captivated me throughout my journeys spanning forty months, 251,000 miles, eighty-five planes, forty cities, every continent, over 12,000 nautical miles across all five oceans and twenty other seas. Those travels provided the stories for this book, a compendium of narratives about this unruly frontier. My goal was not only to report on the plight of sea slaves but also to bring to life the full cast of characters who roam the high seas. They included vigilante conservationists, wreck thieves, maritime mercenaries, defiant whalers, offshore repo men, sea-bound abortion providers, clandestine oil dumpers, elusive poachers, abandoned seafarers, and cast-adrift stowaways.