When I started looking through the stories from Western writers on my desk, I took my pencil and marked the Japanese names and terms that appeared a little off to my Japanese eye. Thats not a Japanese name Id note, or The spelling of the term should be But soon, as I got into each story, I threw my pencil aside. Forget it. Theyre all right just how they are. We know Tagomi doesnt sound like an ordinary Japanese name, but that didnt hurt The Man in the High Castle .

Later, a translation for one of the Japanese stories landed on my desk, and I started reading. Soon, I got a strange feeling Wait. This story can be understood much more clearly in English than in Japanese. What happened? It was as though the story had been waiting to be in English a really long time.

I enjoyed the privilege of being the first reader for all the fantastic works created in the spirit of cross-cultural understanding. This is the moment when weve truly met one another on the same page. Then, whats on the next page? More stories! I hope we can continue to explore this joy of reading together.

Thank you very much to all the contributors and translators who participated in this anthology. And special thanks to our copy editor, Rebecca Downer, who has worked tirelessly on every Haikasoru title.

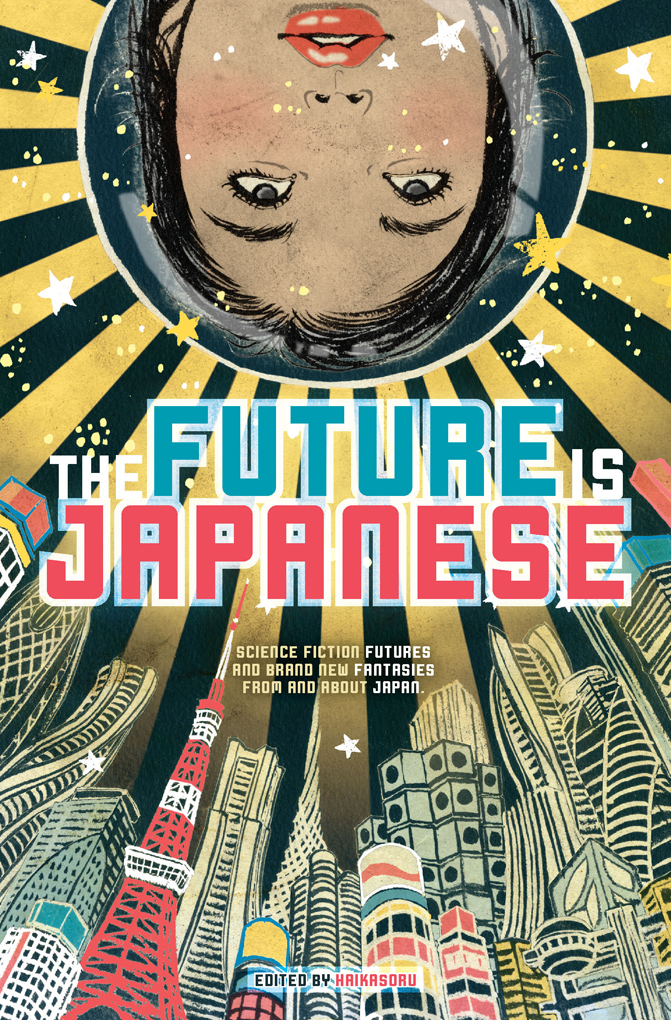

A few years ago, when I accepted a job editing Haikasoru, an imprint of Japanese science fiction, fantasy, and horror, I had little idea of what to expect. There had been some anthologies of Japanese SF in translation, but they tended to concentrate on the historical. Like many people, Id guessed that Japanese SF was heavy on the cyberpunk, with yakuza heroes and flickering neon everywhere, characters motivated by bushido, with the occasional socially relevant story about Japan getting its economic revenge on the US for the Second World War and subsequent occupation. I was wrong. Happily, gloriously wrong.

Japanese science fiction is just like Western science fiction, in that it is hard and soft, dark and whimsical, rigorous and fantastical. Indeed, there are few fans of Western SF as enthusiastic as Japanese SF writers. The Japanese know much about science fiction as it is practiced in the West; Westerners still know too little about Japan. Video games, manga, and anime have filled the knowledge gap, but not completely. My own inaccurate vision of Japanese SF actually came from American science fictional visions of Japanthe neon and the economic rivalry were Western preoccupations. Then theres the problem of Western writers appropriating Japanese cultural concepts and stereotypes of Japanese behaviors and using them as the building blocks for alien species. Reading about Japan in the West is often like looking at a funhouse mirror through a kaleidoscope.

The Future Is Japanese is an attempt to bridge the gap between Western and Japanese SF and fantasy. Many of our Japanese con- tributors wrote pieces specifically for this projecttheir work is appearing in translation here before being published in their native language. And the Western writers, many of whom have some personal connection to Japan, pulled out all the aesthetic stops. Yes, there are virtual worlds and kanji and even a squadron of giant mecha , and the stories are as authentic as they are fantastical. SF writers have always explored strange new worldswith The Future Is Japanese , we explore our own.

Nick Mamatas

San Francisco, California

February 2012

The world is shaped like the kanji for umbrella , only written so poorly, like my handwriting, that all the parts are out of proportion.

My father would be greatly ashamed at the childish way I still form my characters. Indeed, I can barely write many of them anymore. My formal schooling back in Japan had ceased when I was only eight.

Yet for present purposes, this badly drawn character will do.

The canopy up there is the solar sail. Even that distorted kanji can only give you a hint of its vast size. A hundred times thinner than rice paper, the spinning disc fans out a thousand kilometers into space like a giant kite intent on catching every passing photon. It literally blocks out the sky.

Beneath it dangles a long cable of carbon nanotubes a hundred kilometers long: strong, light, and flexible. At the end of the cable hangs the heart of the Hopeful , the habitat module, a five-hundred-meter-tall cylinder into which all the 1,021 inhabitants of the world are packed.

The light from the sun pushes against the sail, propelling us on an ever-widening, ever-accelerating, spiraling orbit away from it. The acceleration pins all of us against the decks, gives everything weight.

Our trajectory takes us toward a star called 61 Virginis. You cant see it now because it is behind the canopy of the solar sail. The Hopeful will get there in about three hundred years, more or less. With luck, my great-great-greatI calculated how many greats I need once, but I dont remember nowgrandchildren will see it.

There are no windows in the habitat module, no casual view of the stars streaming past. Most people dont care, having grown bored of seeing the stars long ago. But I like looking through the cameras mounted on the bottom of the ship so that I can gaze at this view of the receding, reddish glow of our sun, our past.

Hiroto, Dad said as he shook me awake. Pack up your things. Its time.