Contents

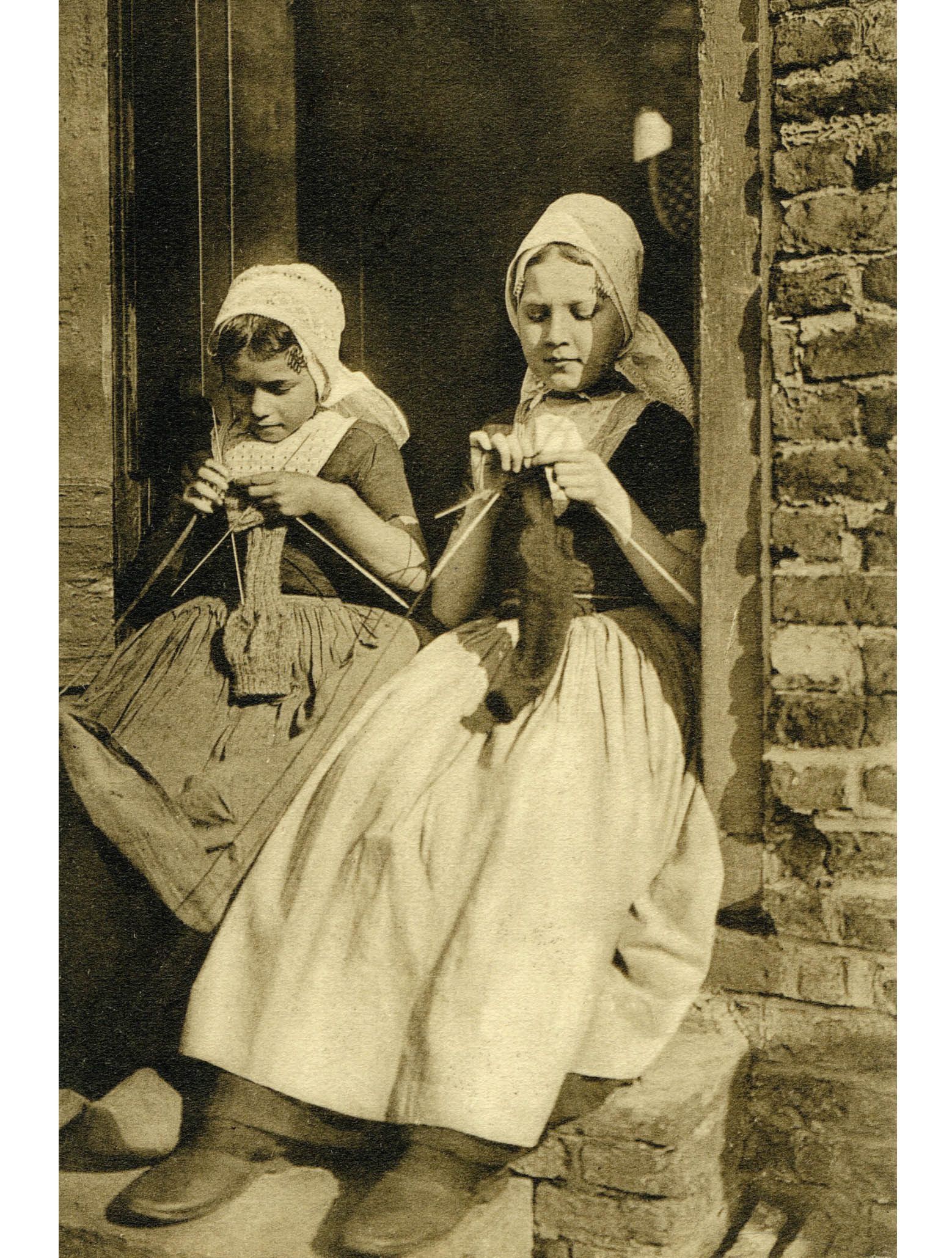

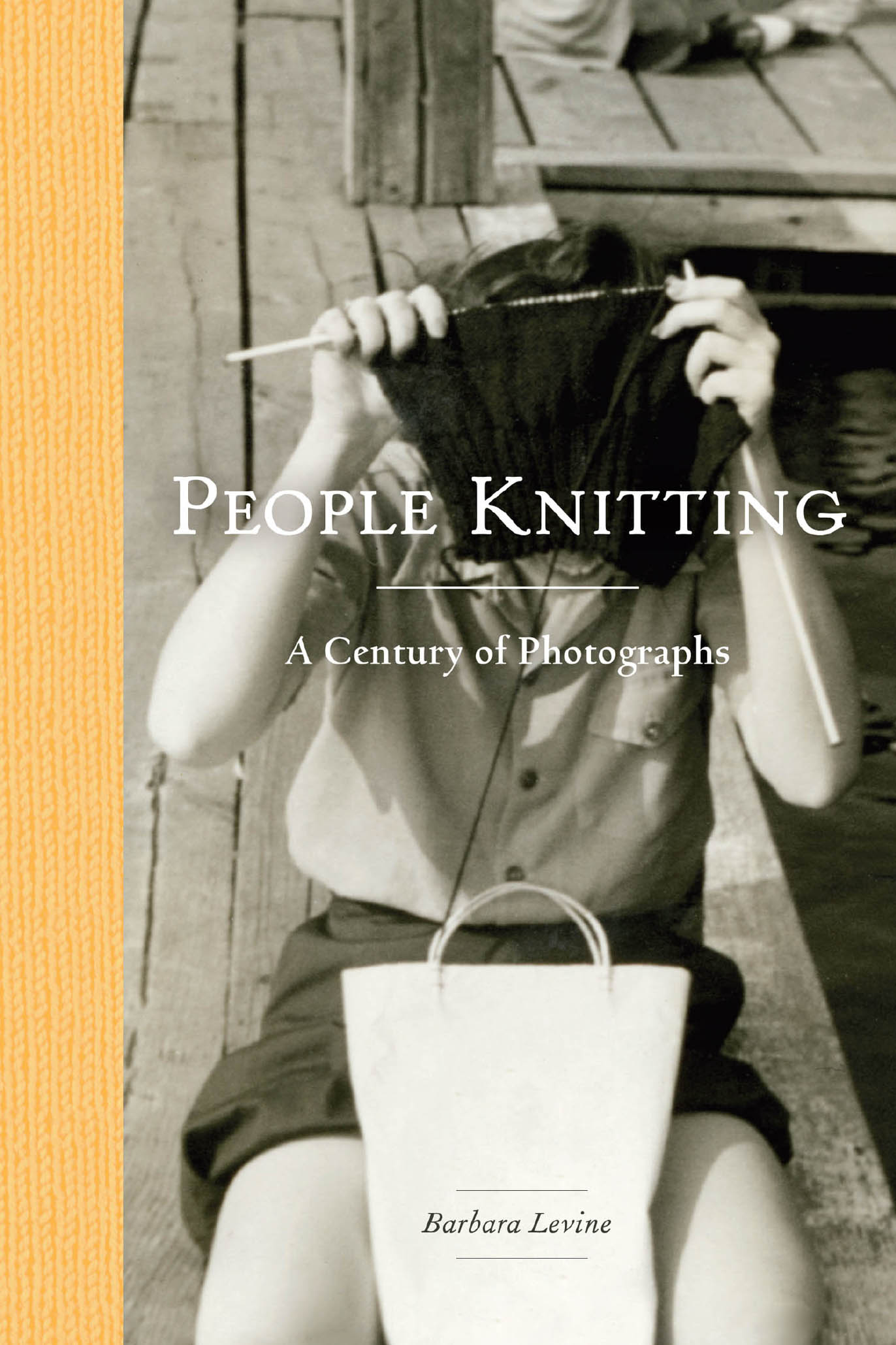

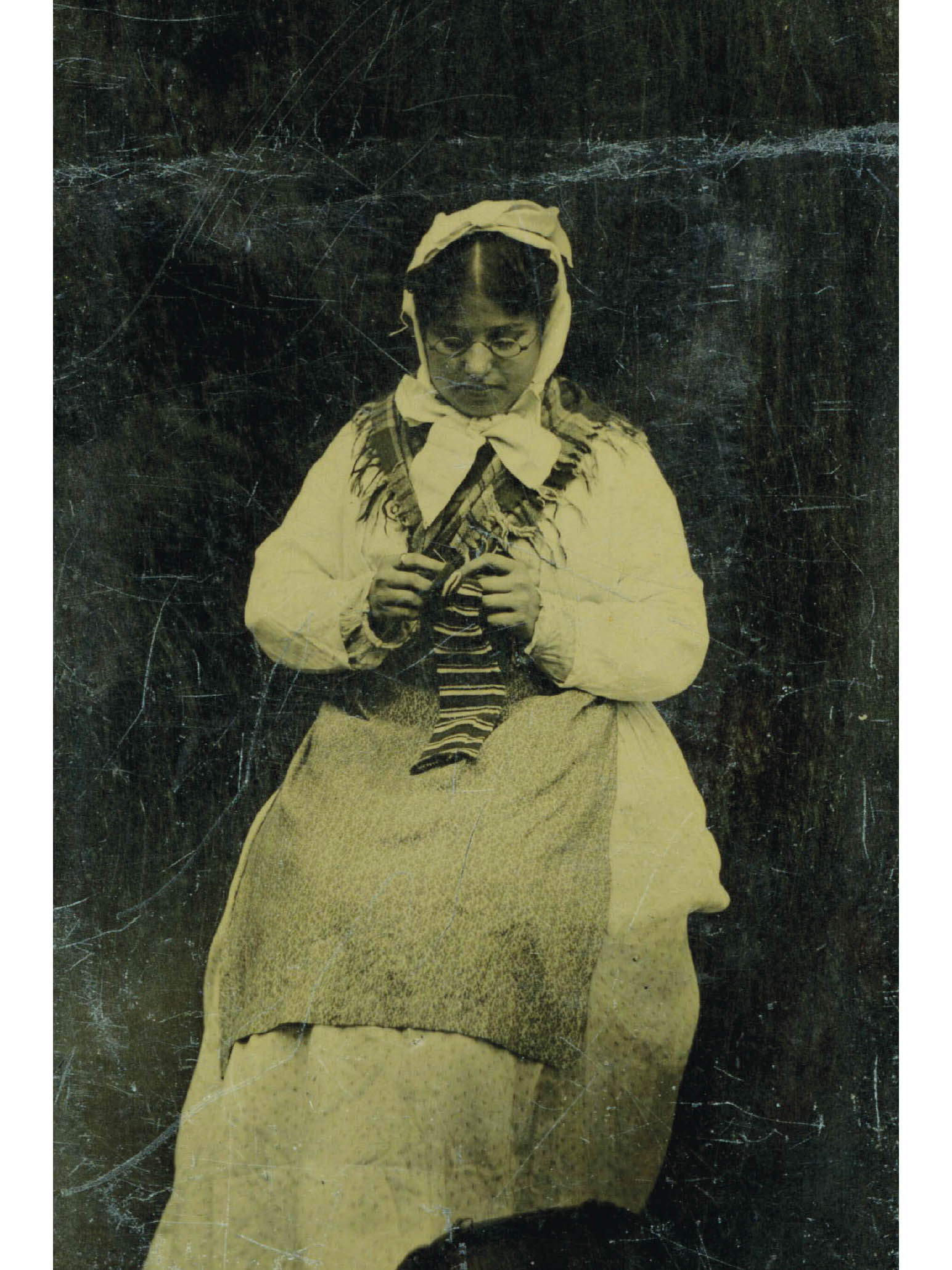

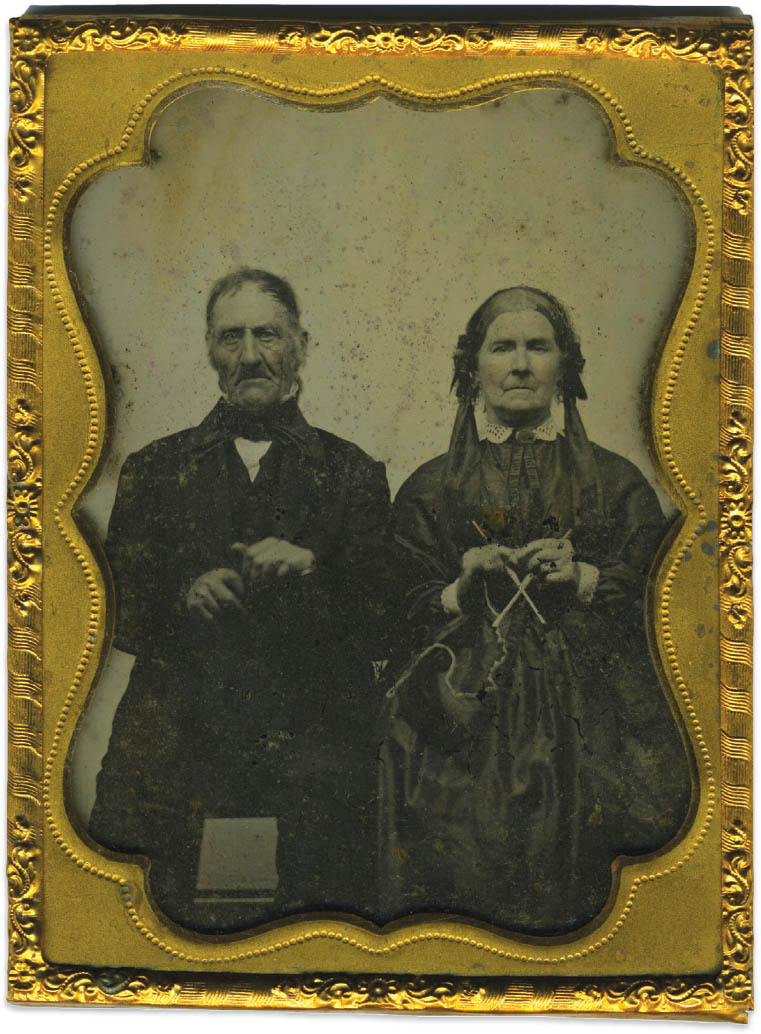

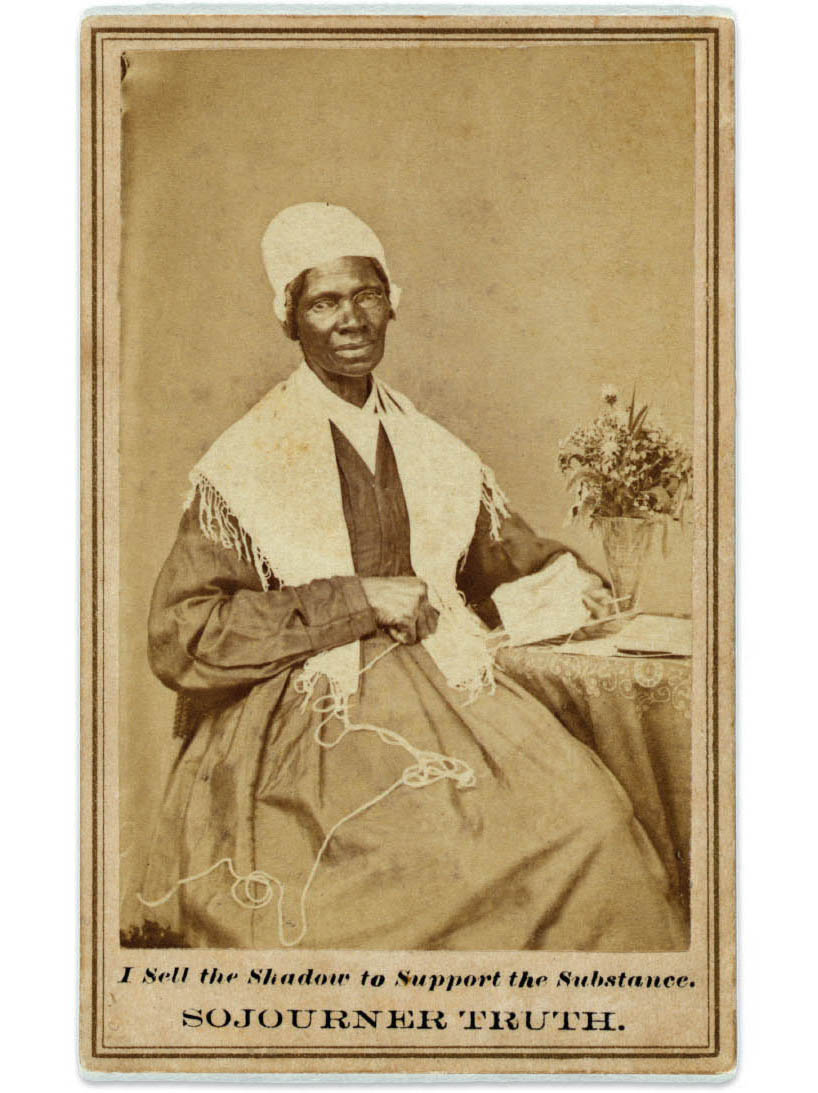

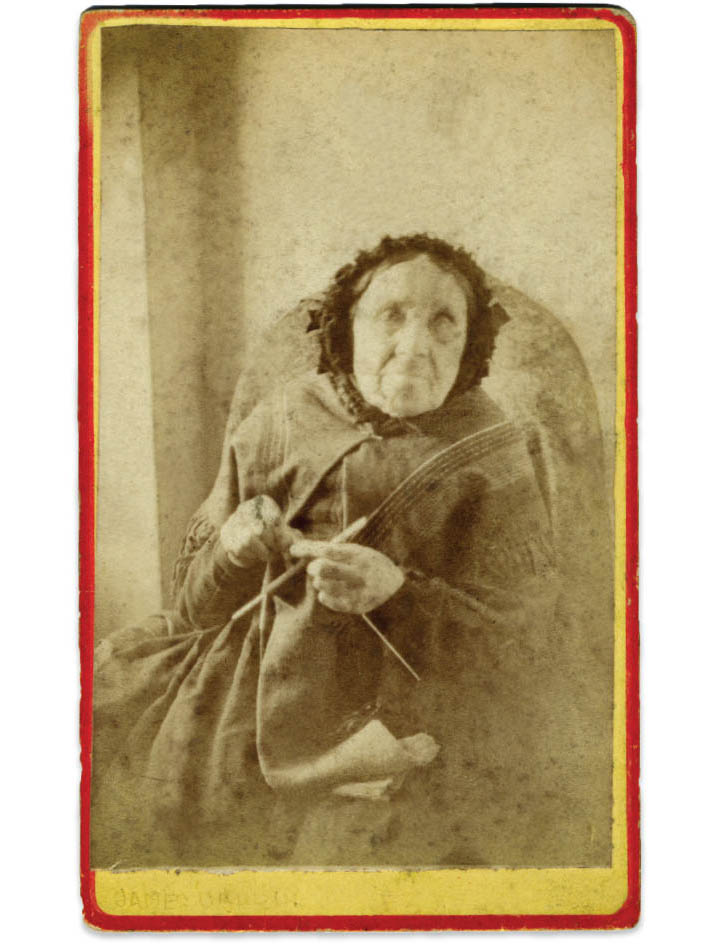

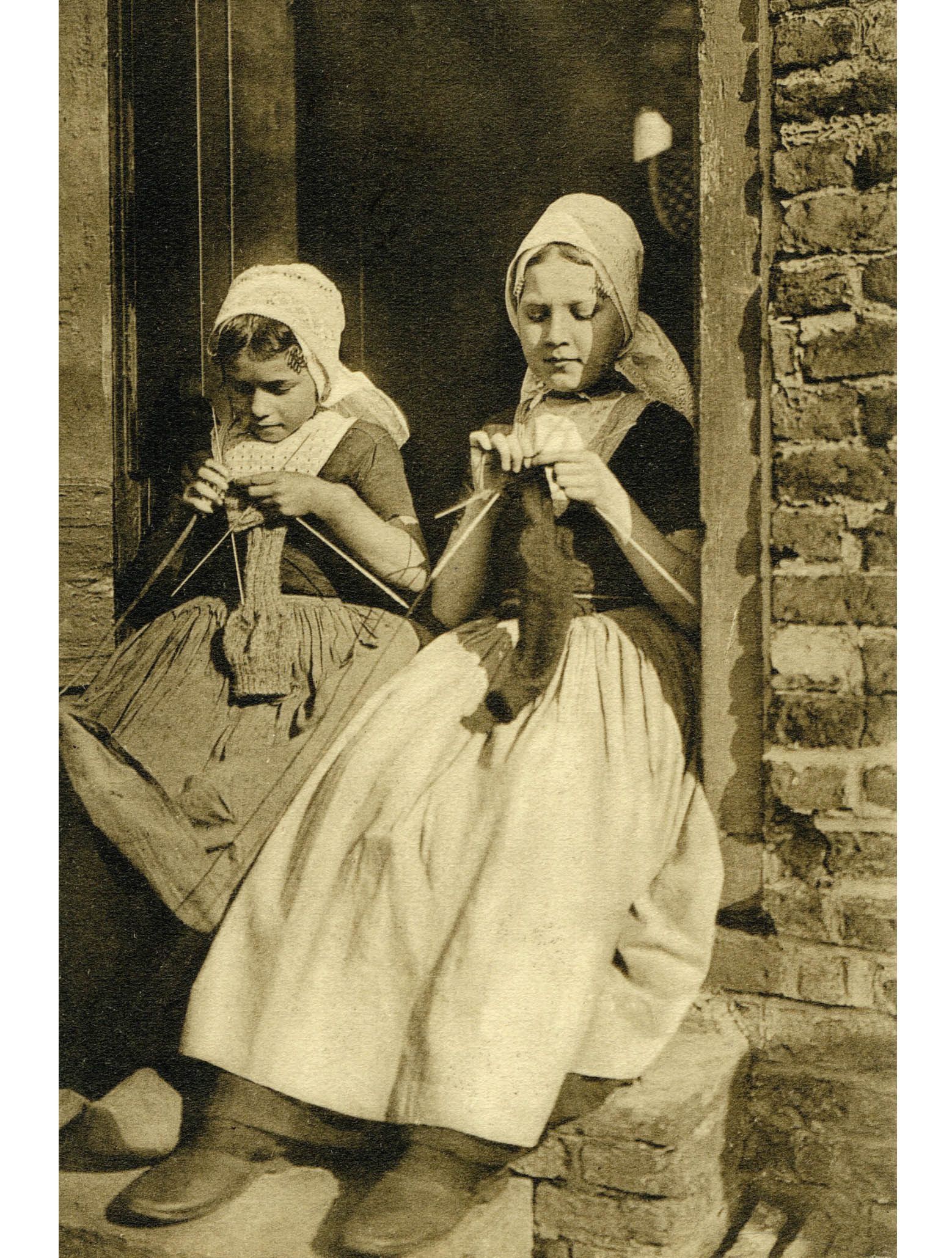

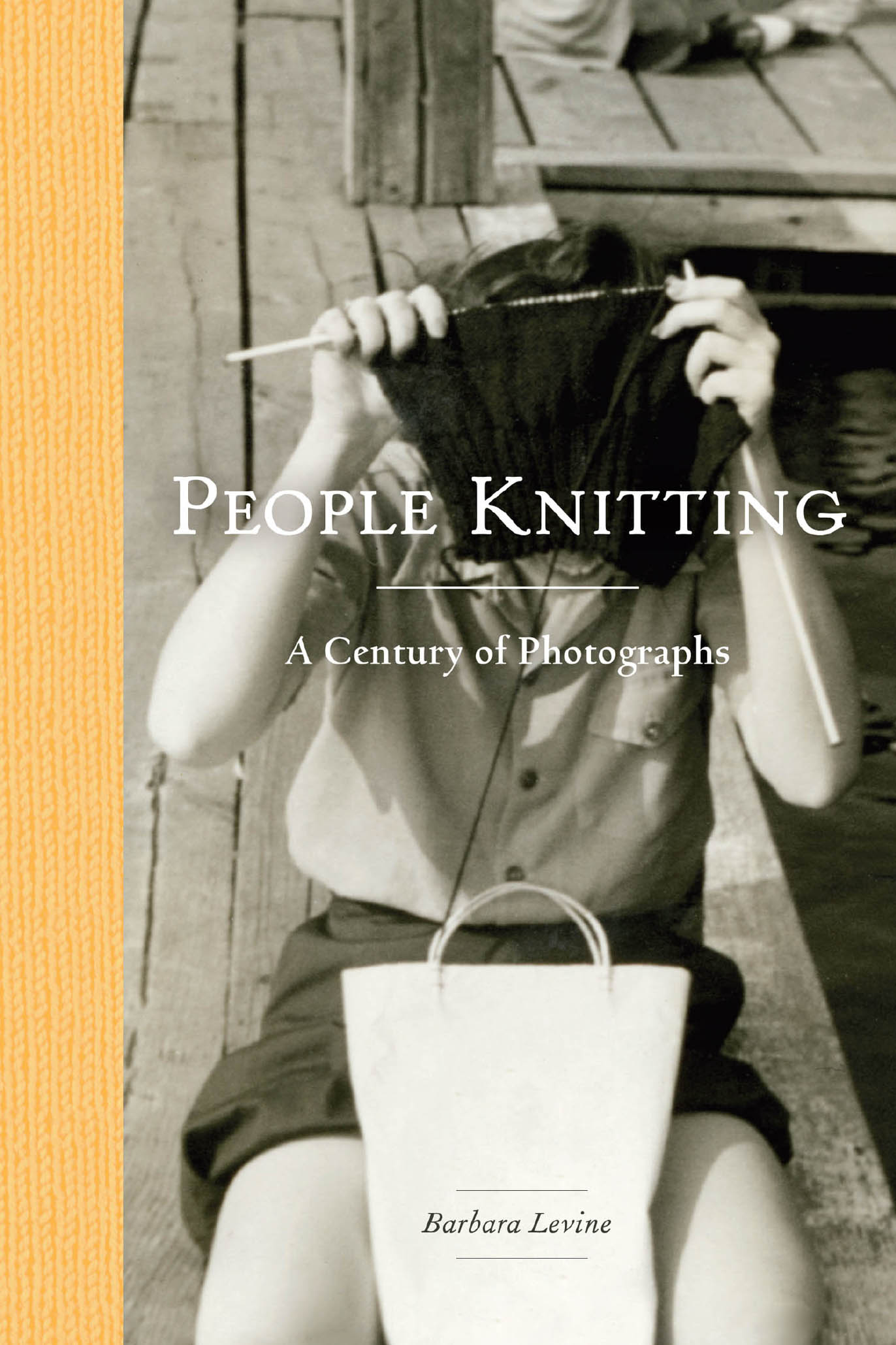

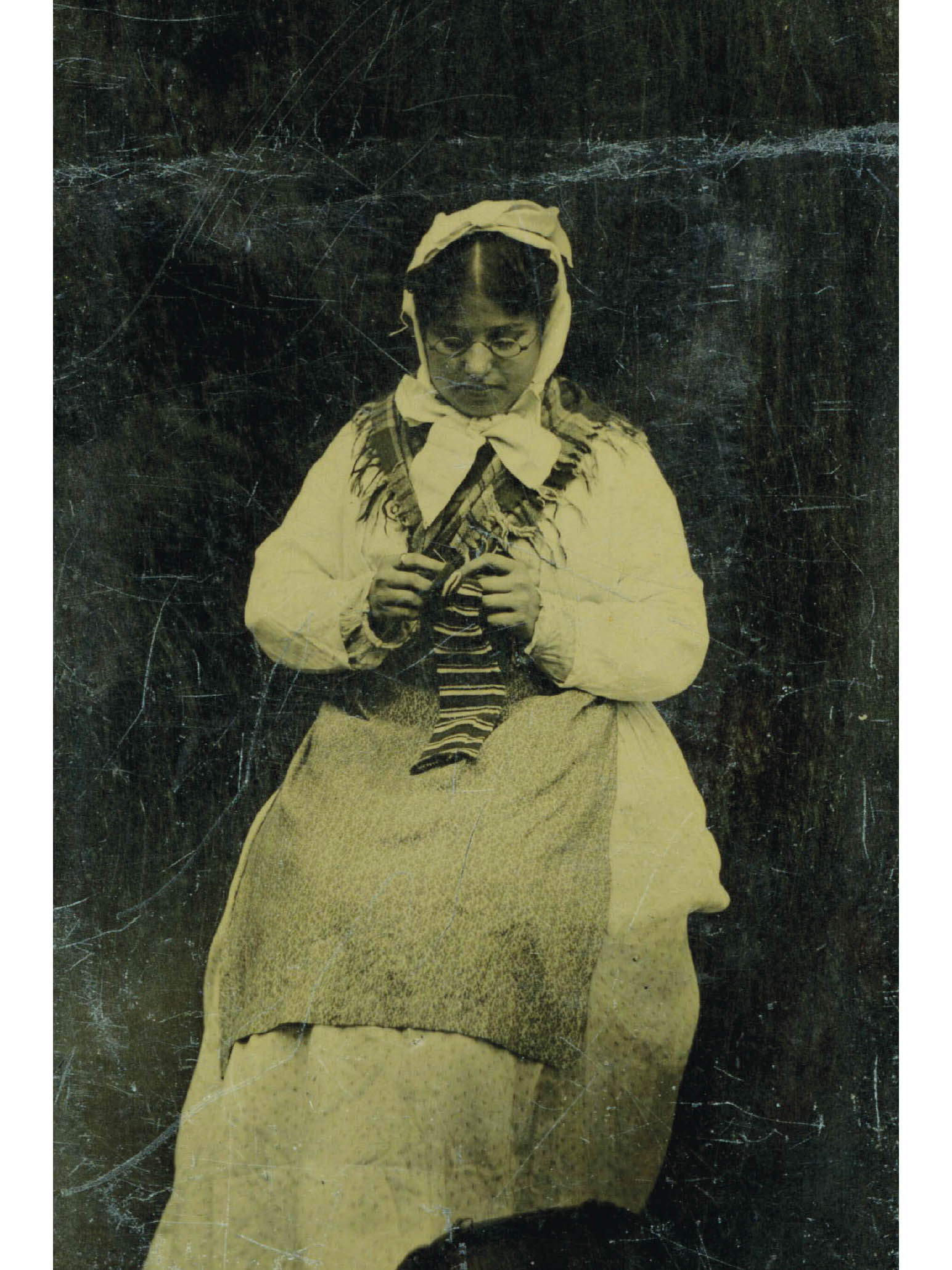

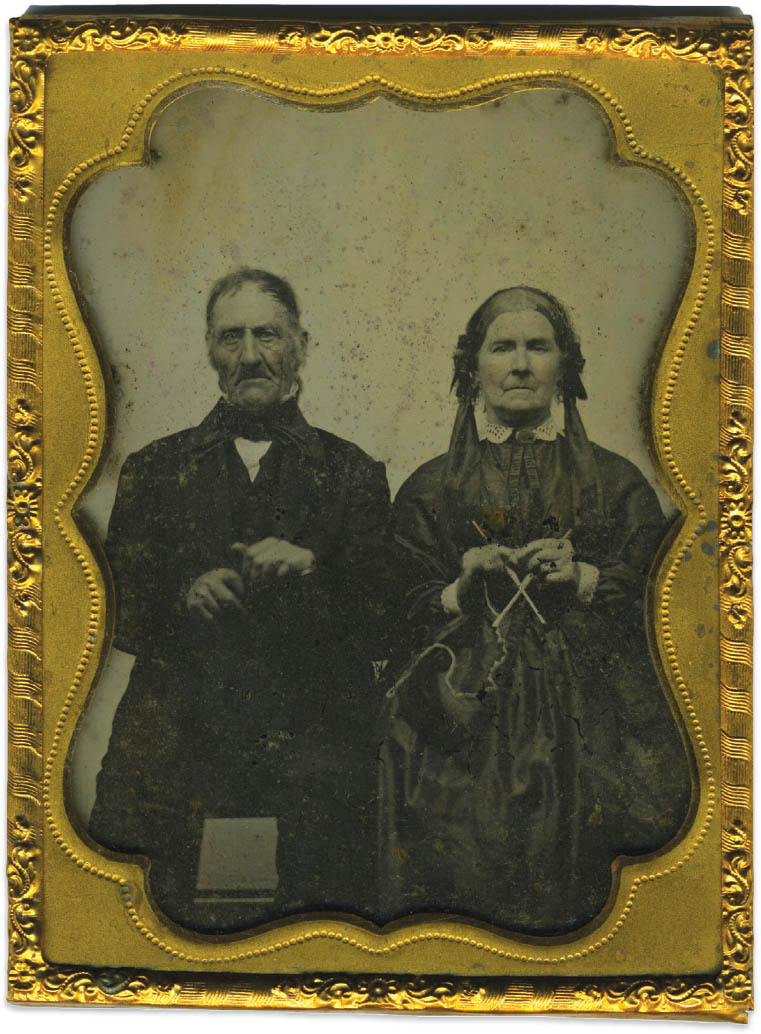

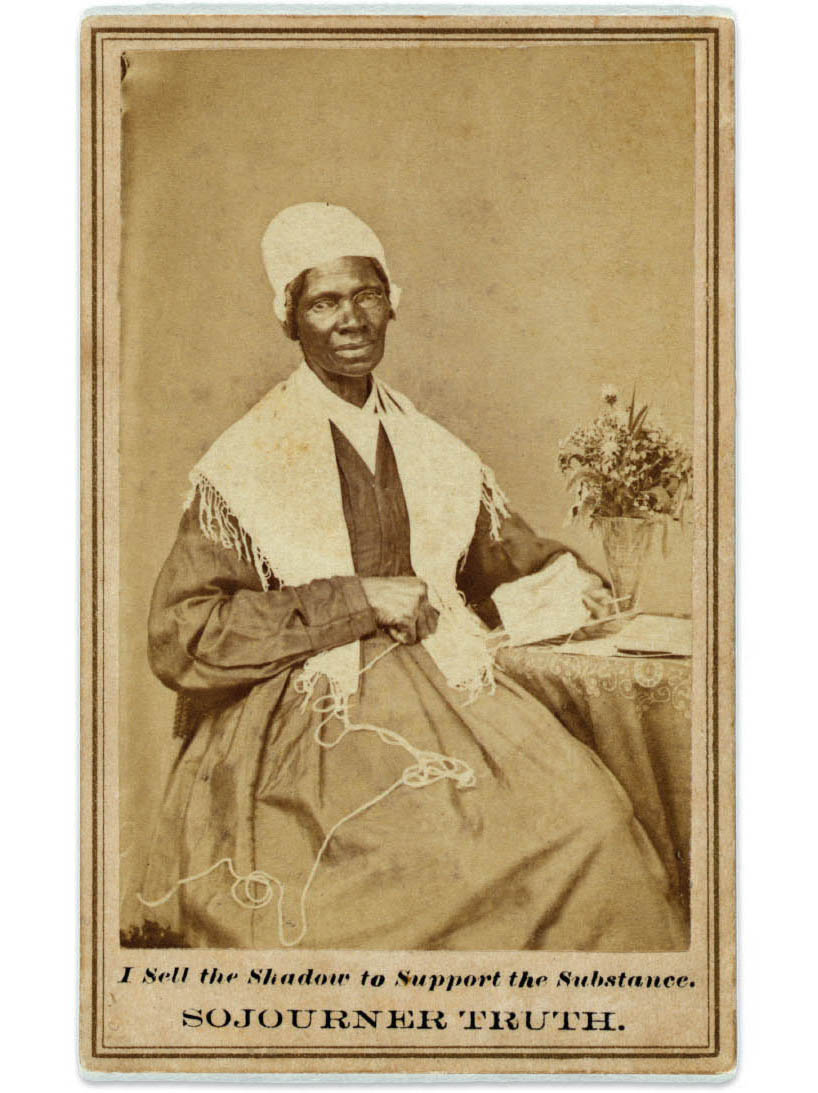

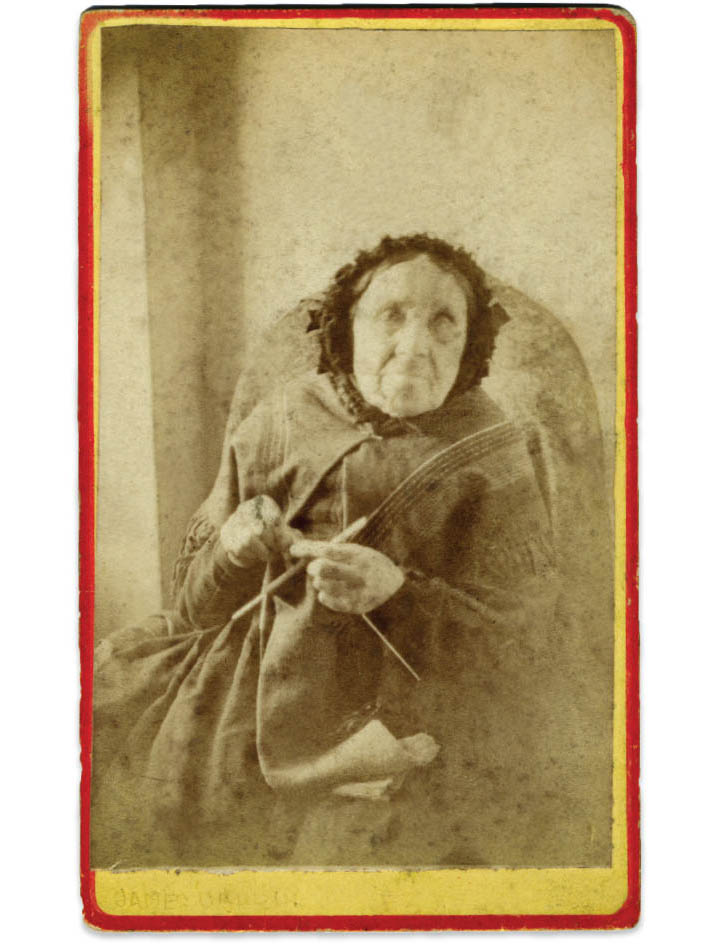

T he one hundred photographs in this book, dating from the 1860s to the 1960s, are of people knitting. They come primarily from my personal collection of vintage vernacular photographs, which I started over twenty-five years ago when a passion for old photographs took hold of me. Without fail, whenever I find a snapshot of someone knitting it makes me think of my mother. One of my earliest memories of my mother was watching her knit and listening to the sound of knitting needles constantly clicking. The combination of her intense focus on what she was doing and the rhythmic sound of her needles

click,

click,

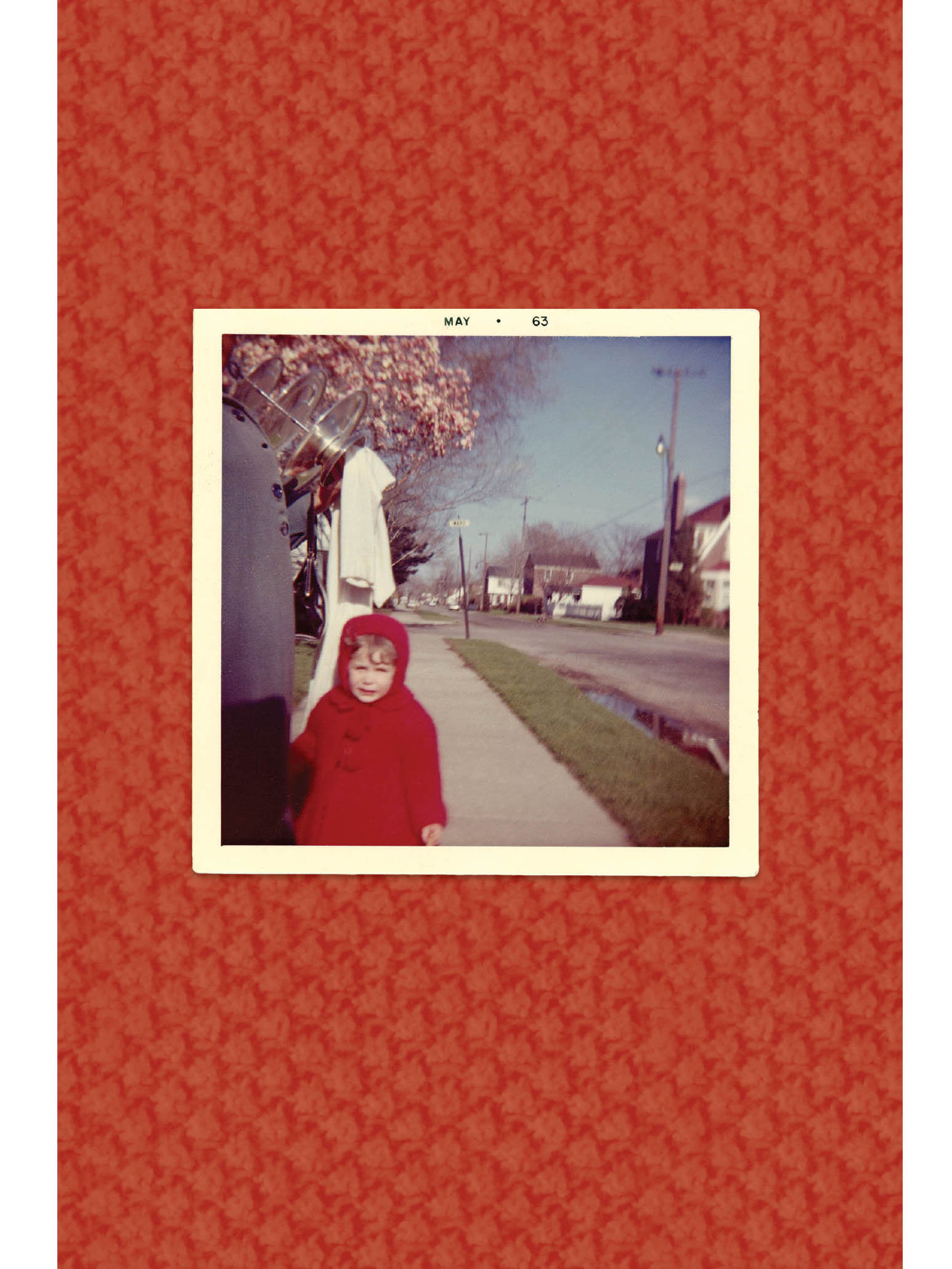

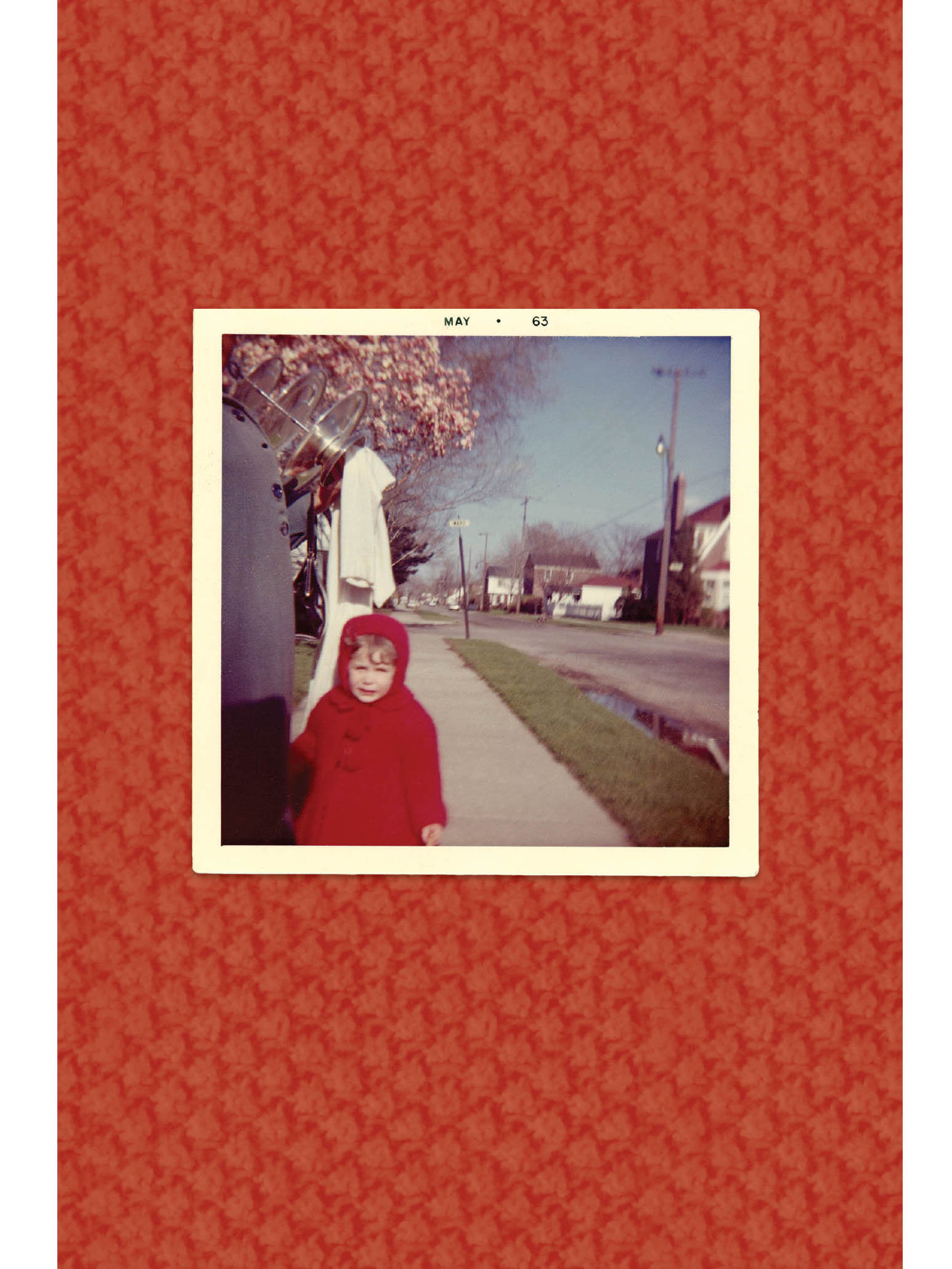

clicking created an air in the room that signaled something important was happening. Whenever my mother was in her knitting trance (as I called it), I knew not to interrupt her, and often I would complain: All you do is knit! I do not have a single snapshot of my mother knitting, but I do have photos of me as a child wearing many of her creations.

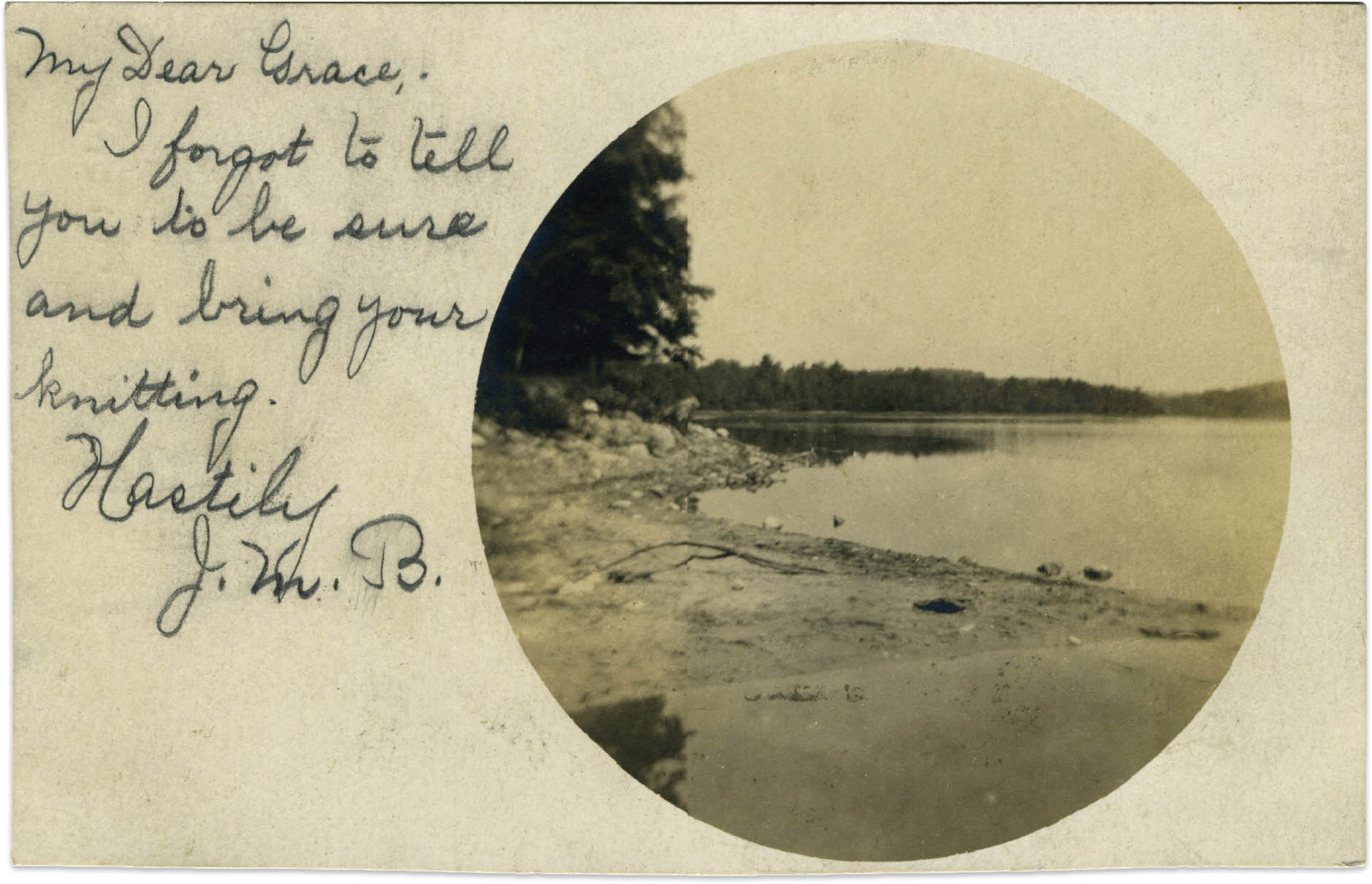

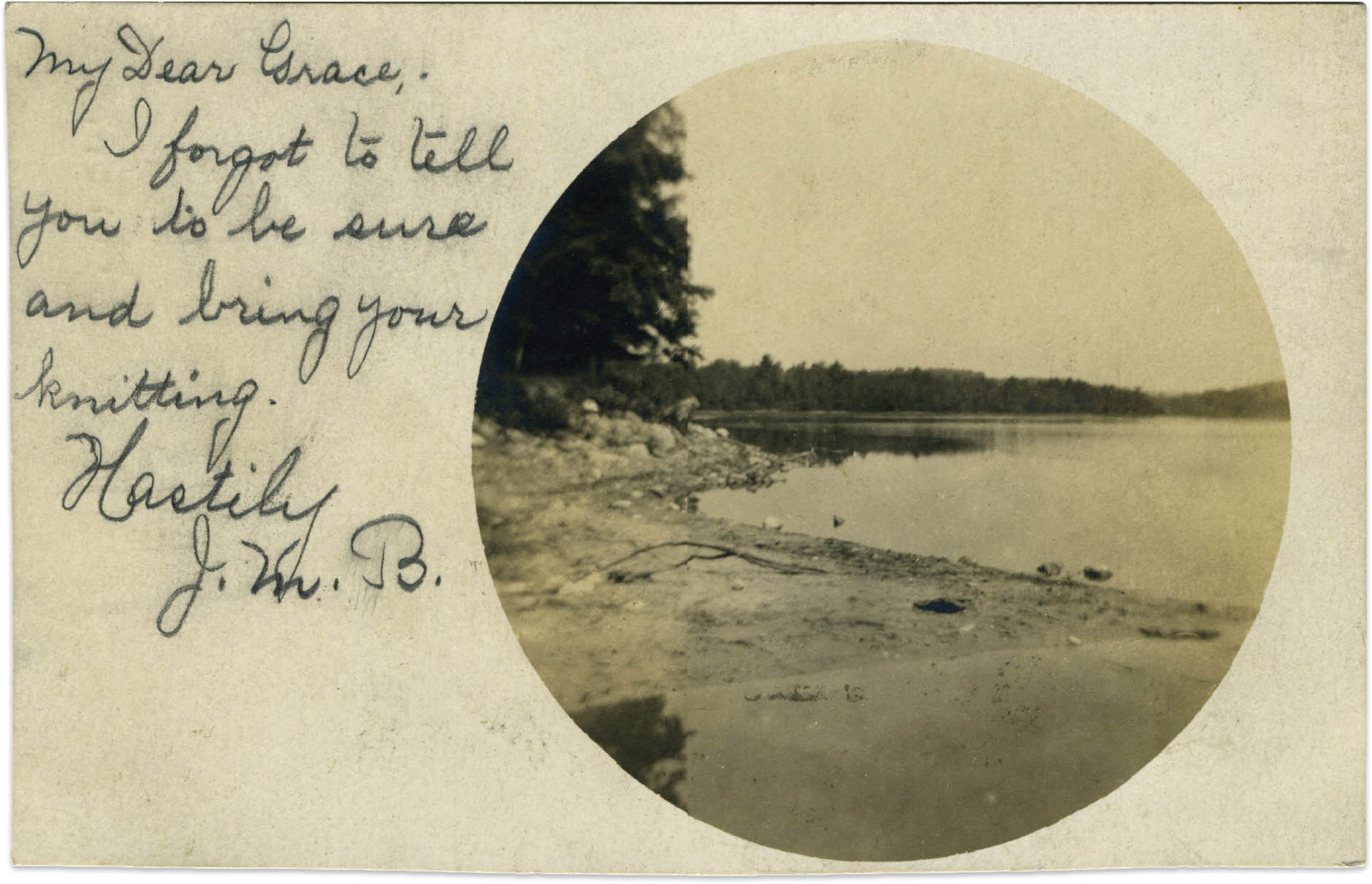

Here I am at age three standing on our Detroit sidewalk, shrouded in a blazing red mohair coat and hat that she made for me. It was hard to smile for the camera while clad head to toe in scratchy mohair on an unusually warm May day! I have never been a knitter, but I guess I could call myself a knitter-watcher. It is mesmerizing, even awe-inspiring, to see a ball of yarn transformed through some magical choreography of fingers and needles into items functional or fanciful. Yet, if youre a non-knitter, observing a knitter can also be baffling. To watch people knit is to be invited into their private world of contemplation and innermost creative expression, but at the same time, they are preoccupiedmapping out a pattern, counting a line, envisioning some future garment that you cant imagine and may never see. I have a special fascination for the intersection of knitting and photography.

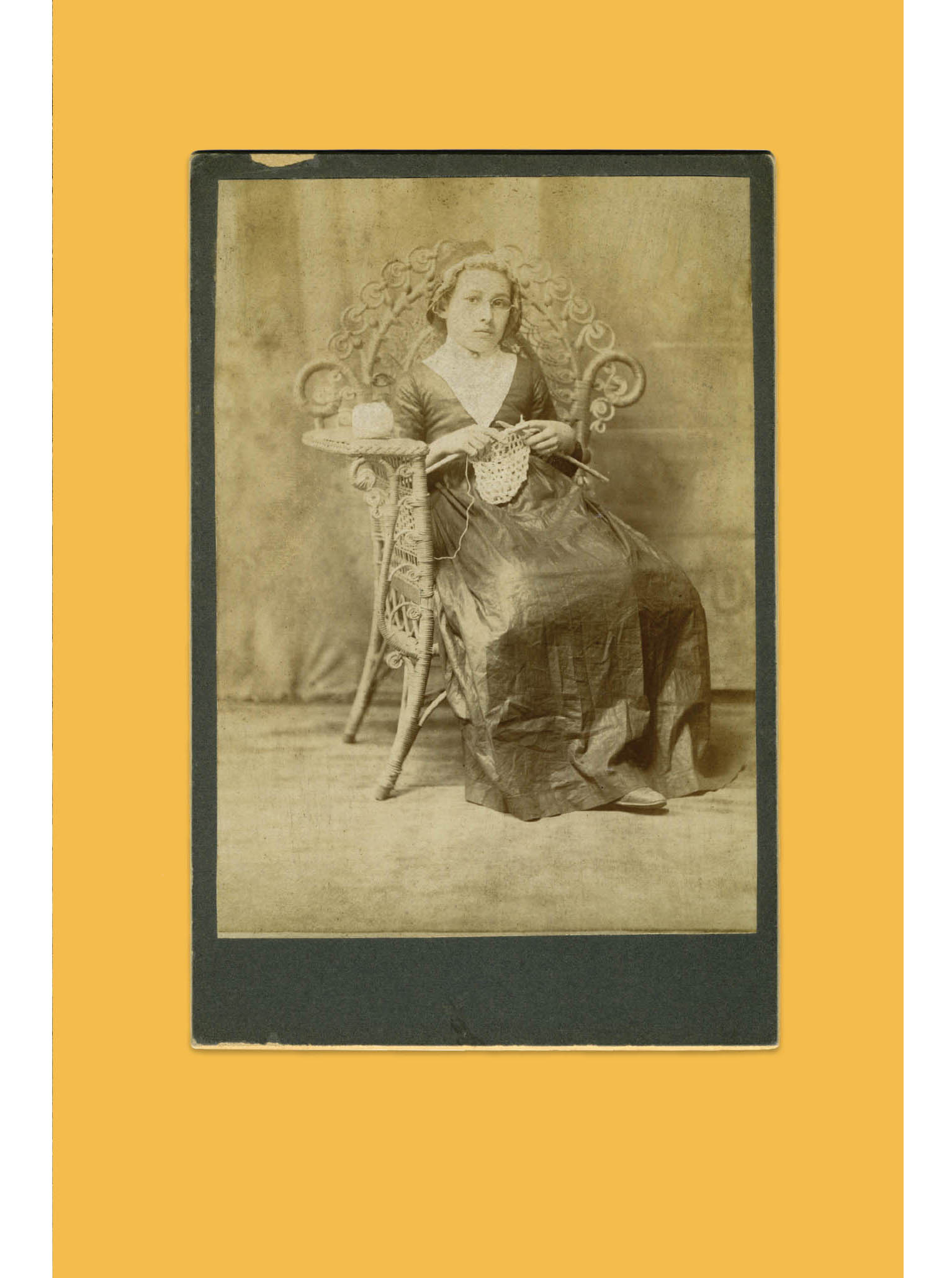

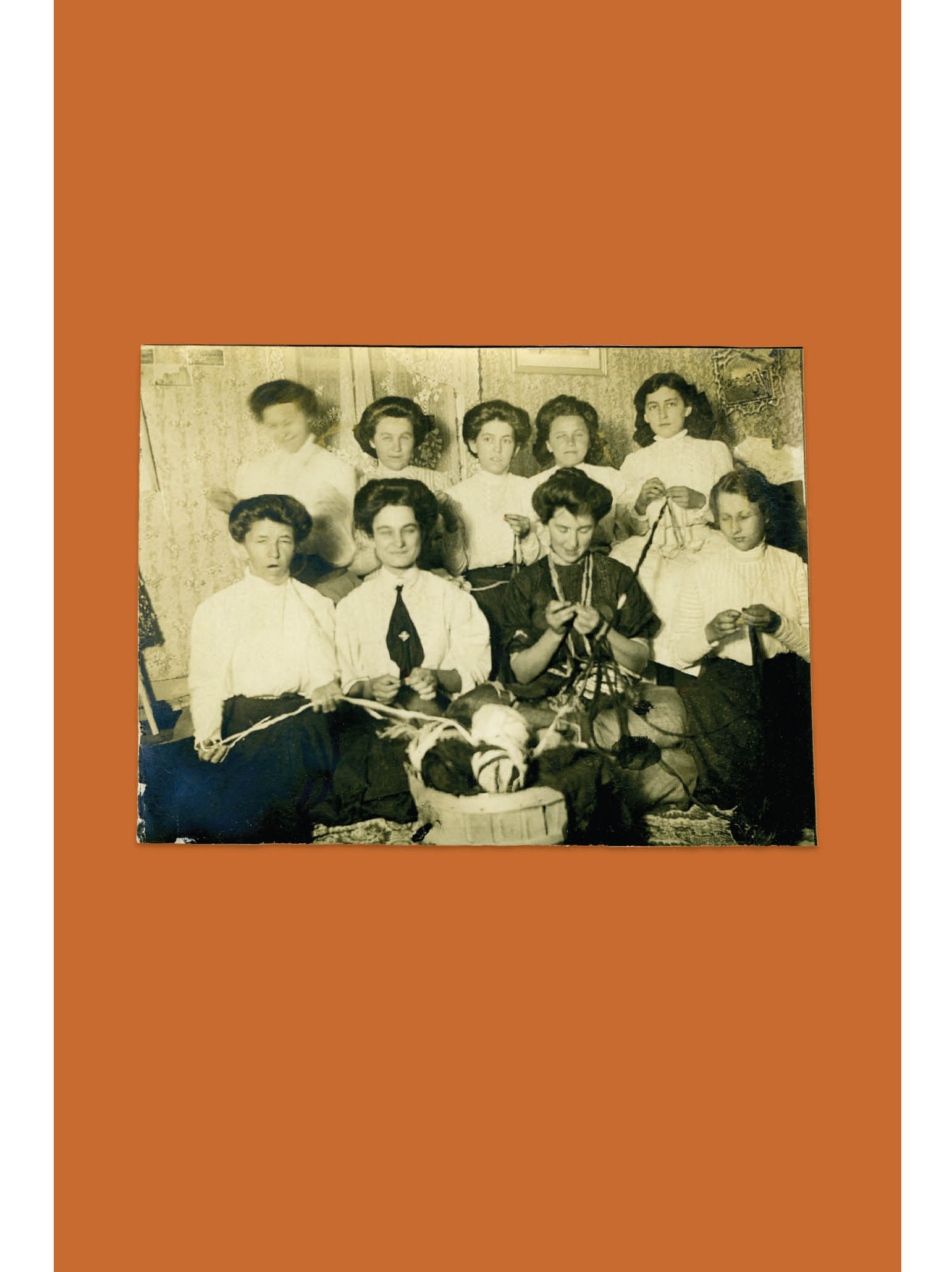

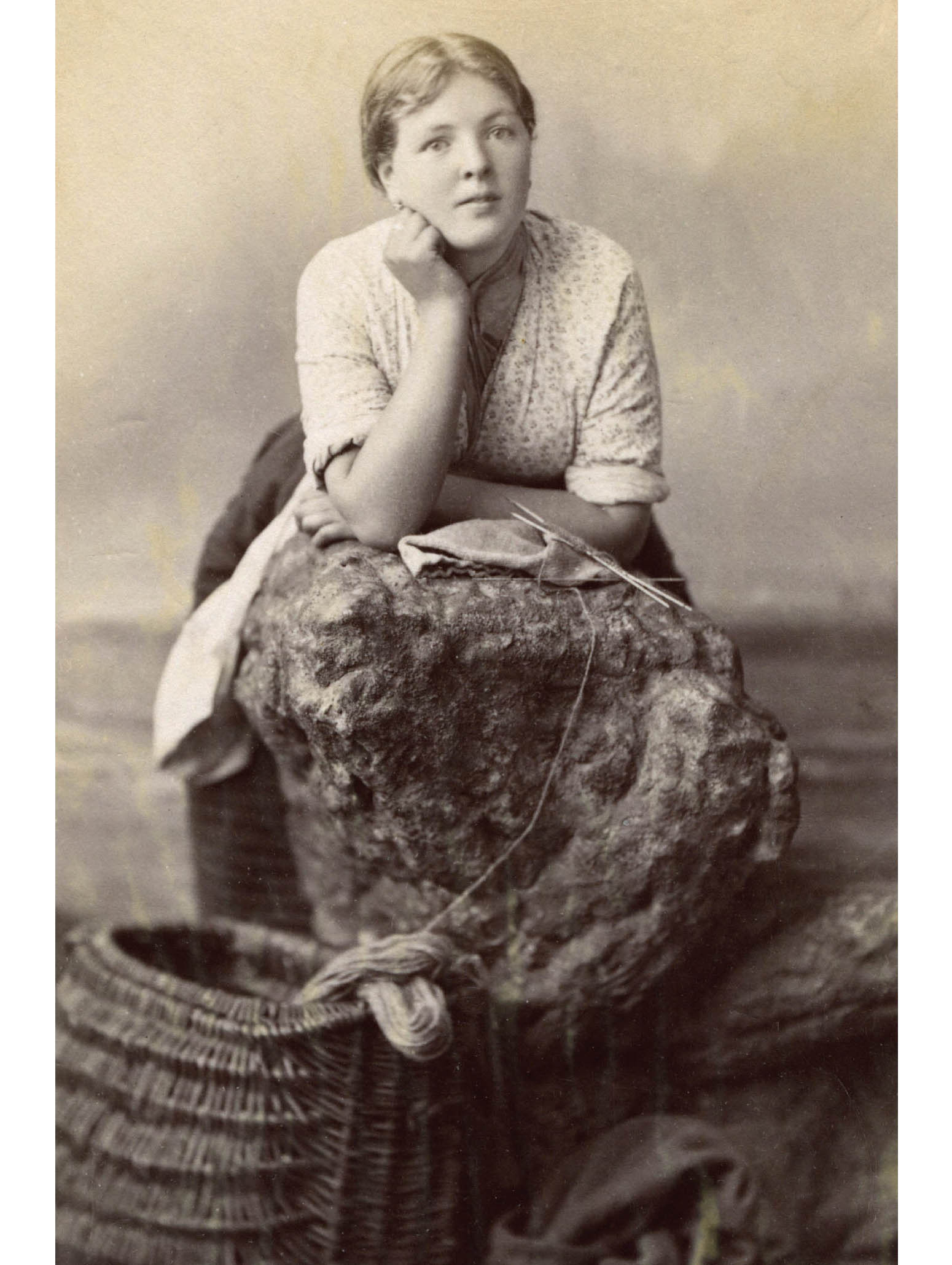

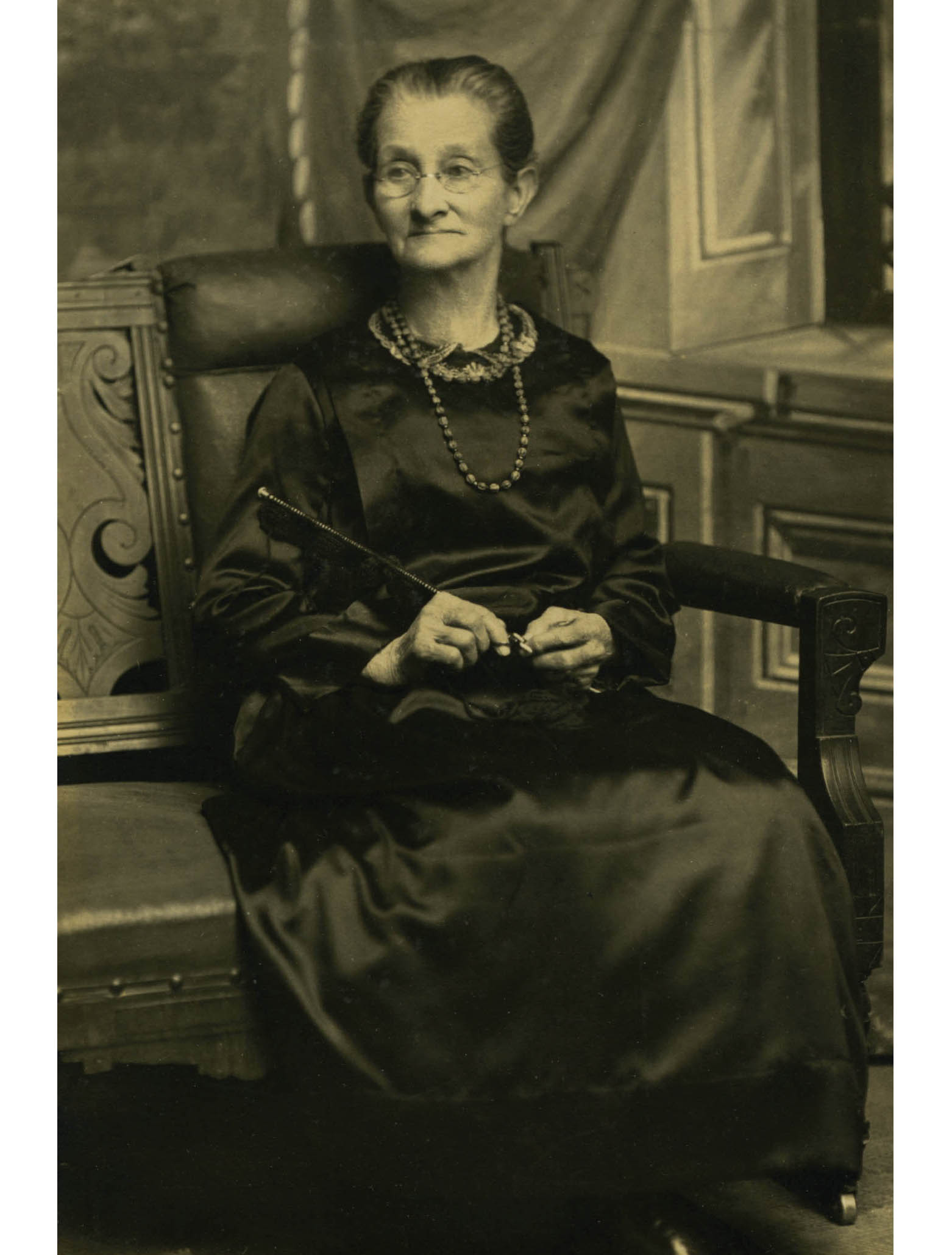

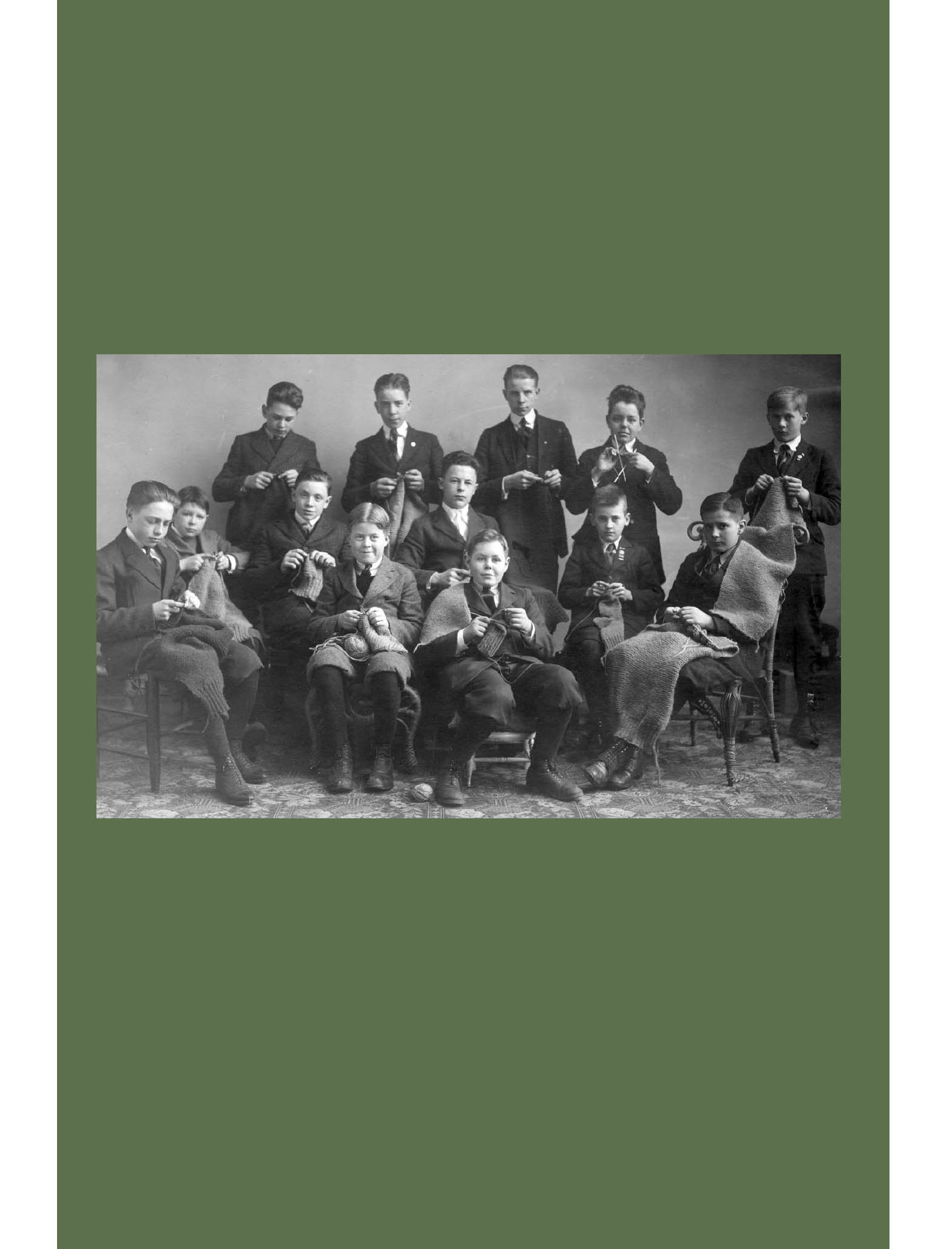

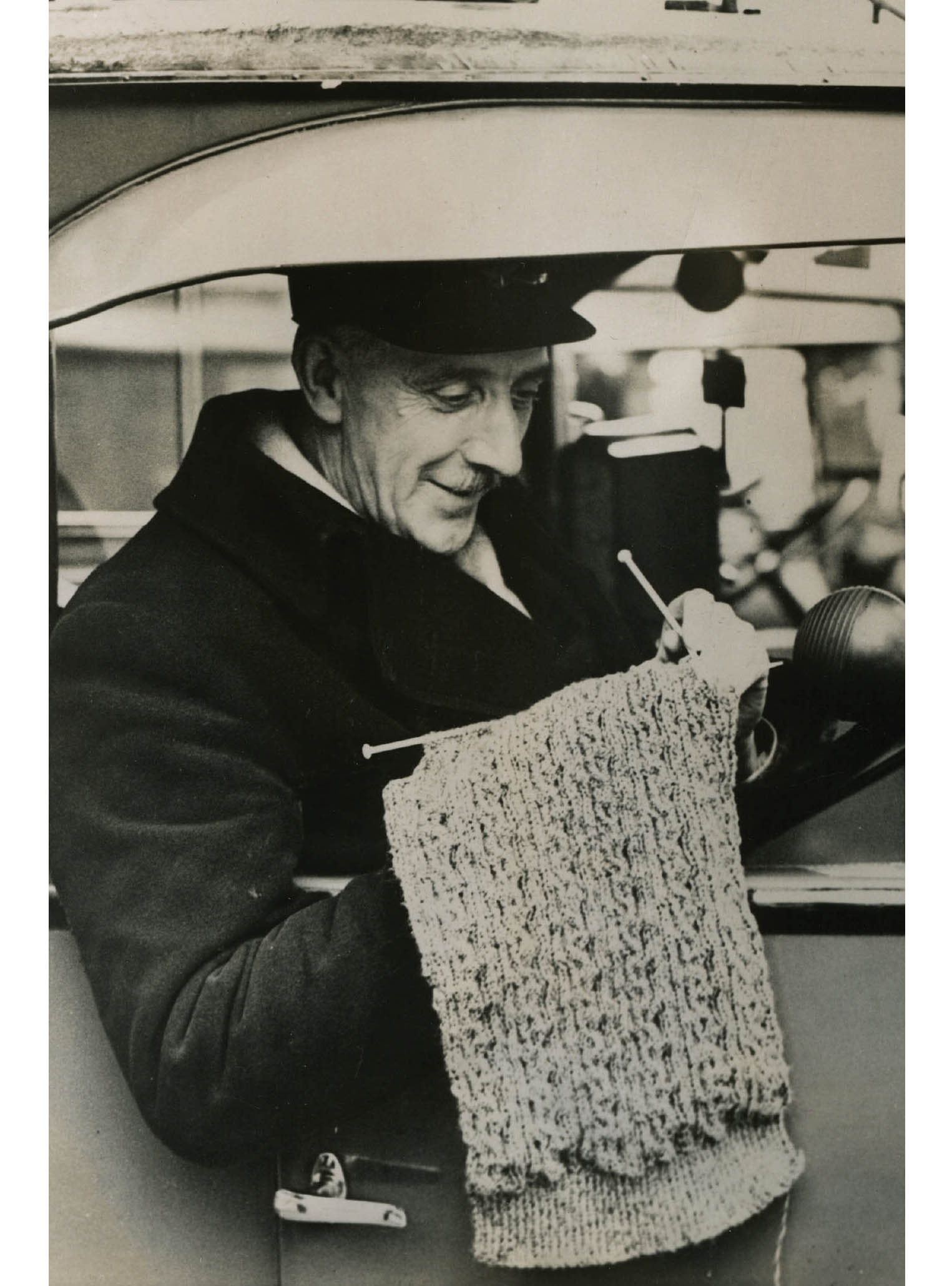

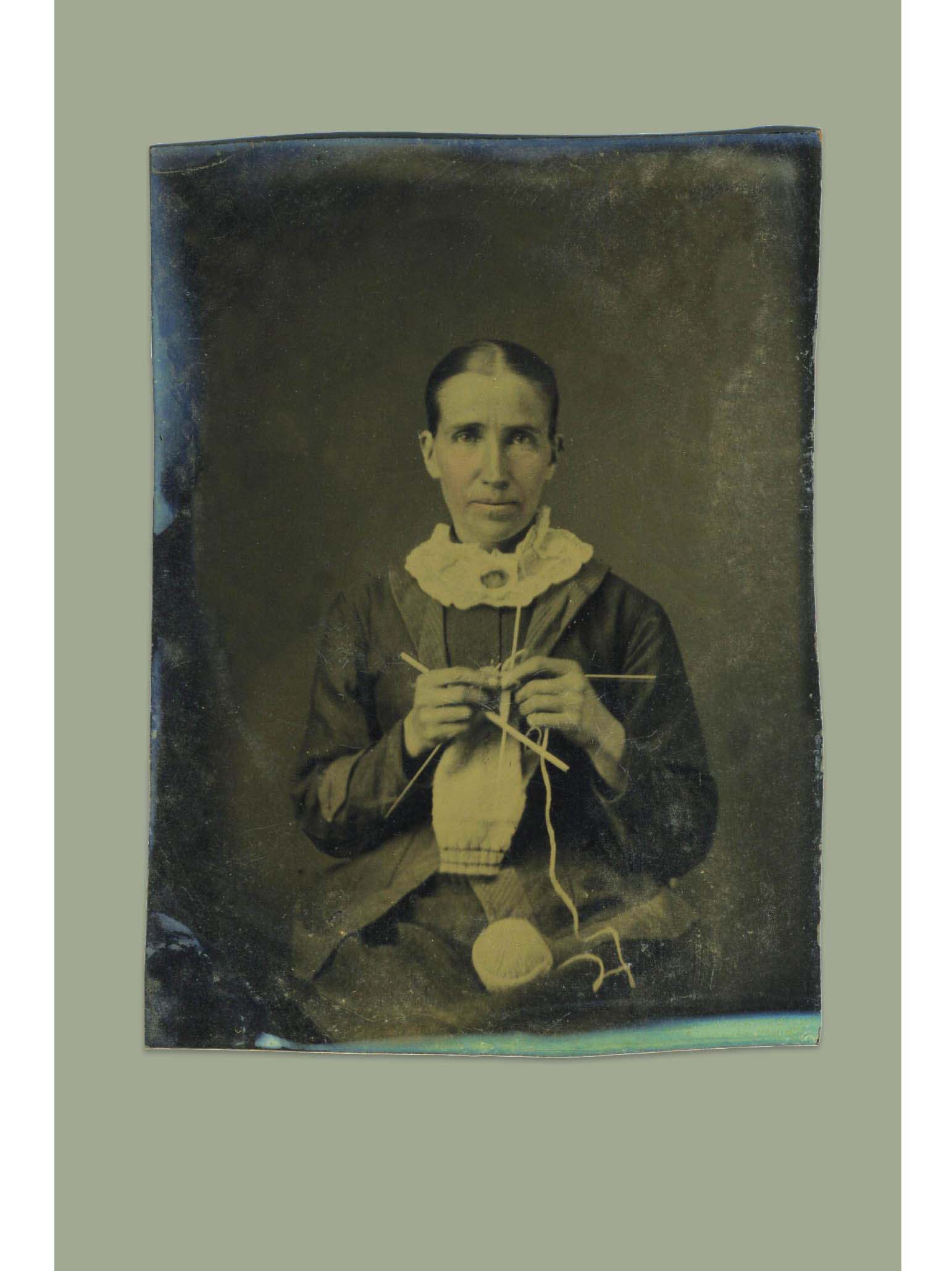

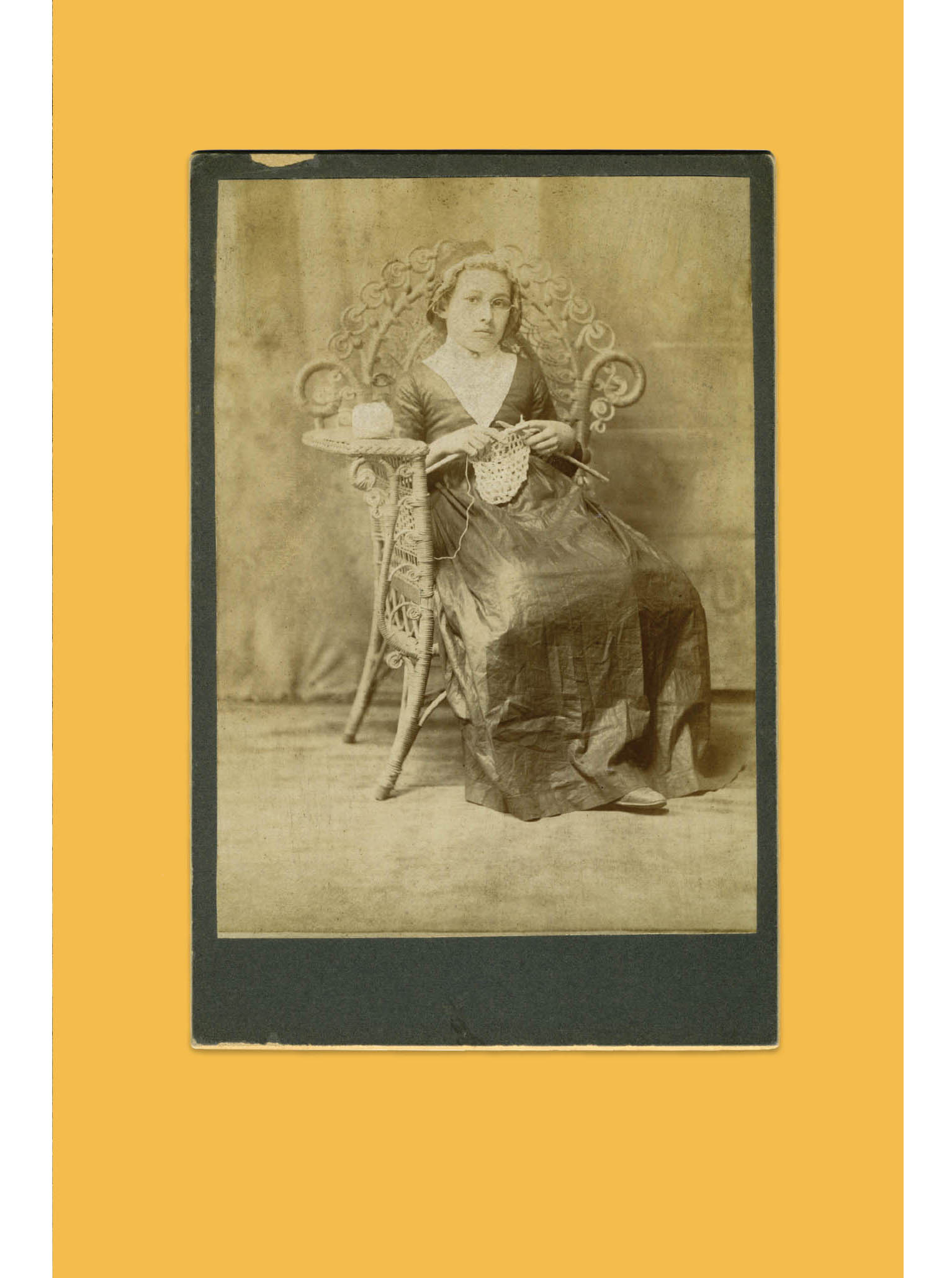

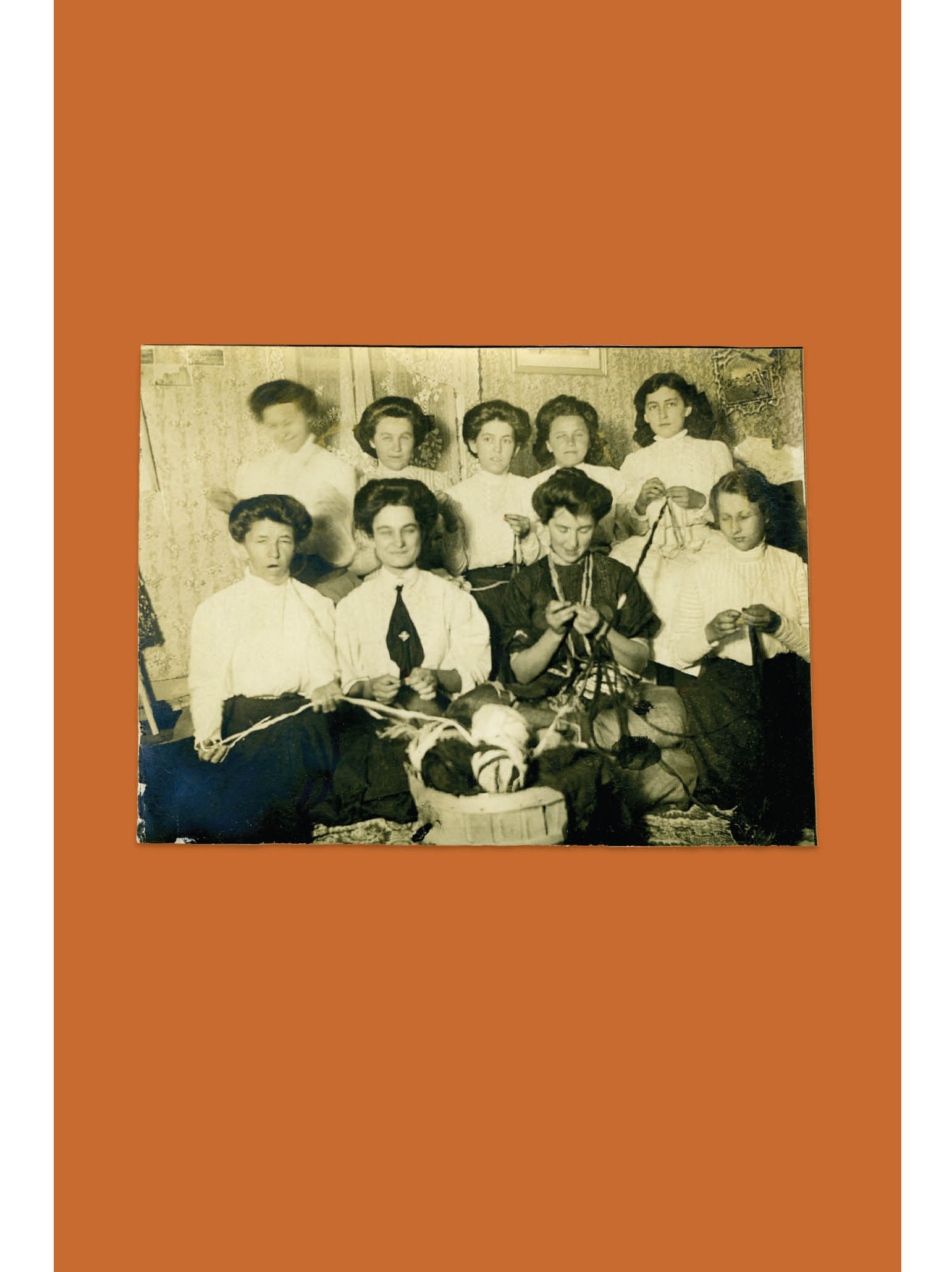

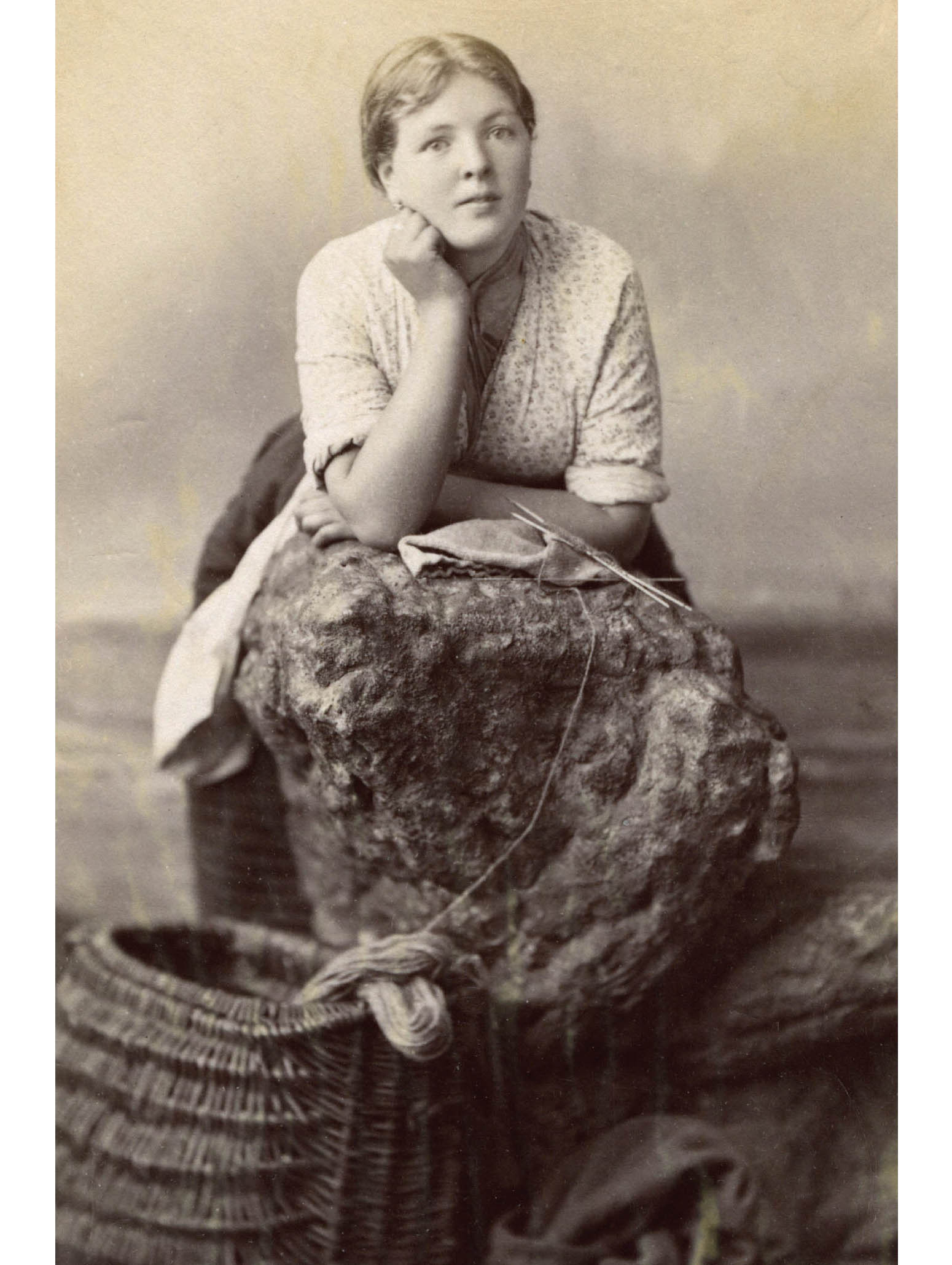

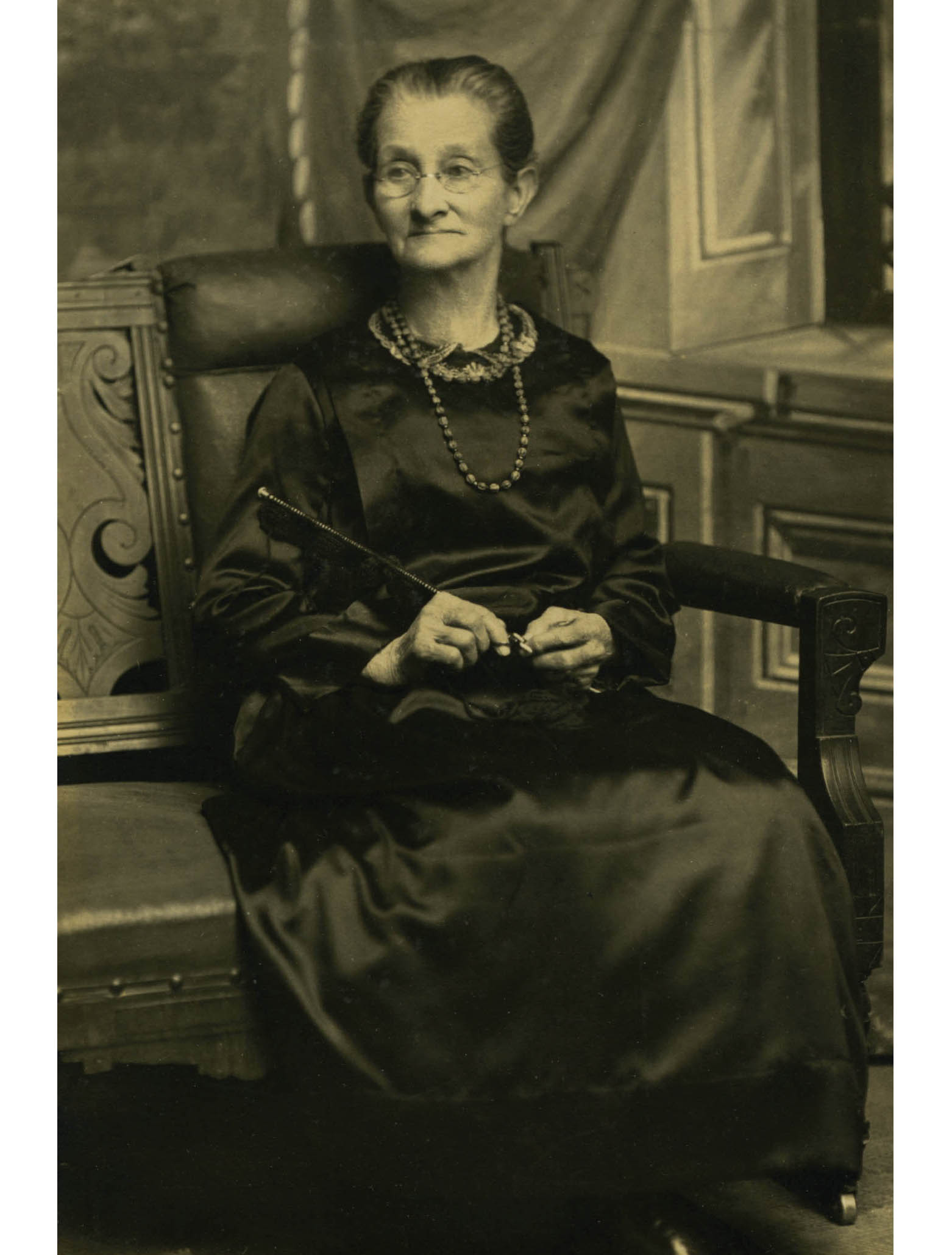

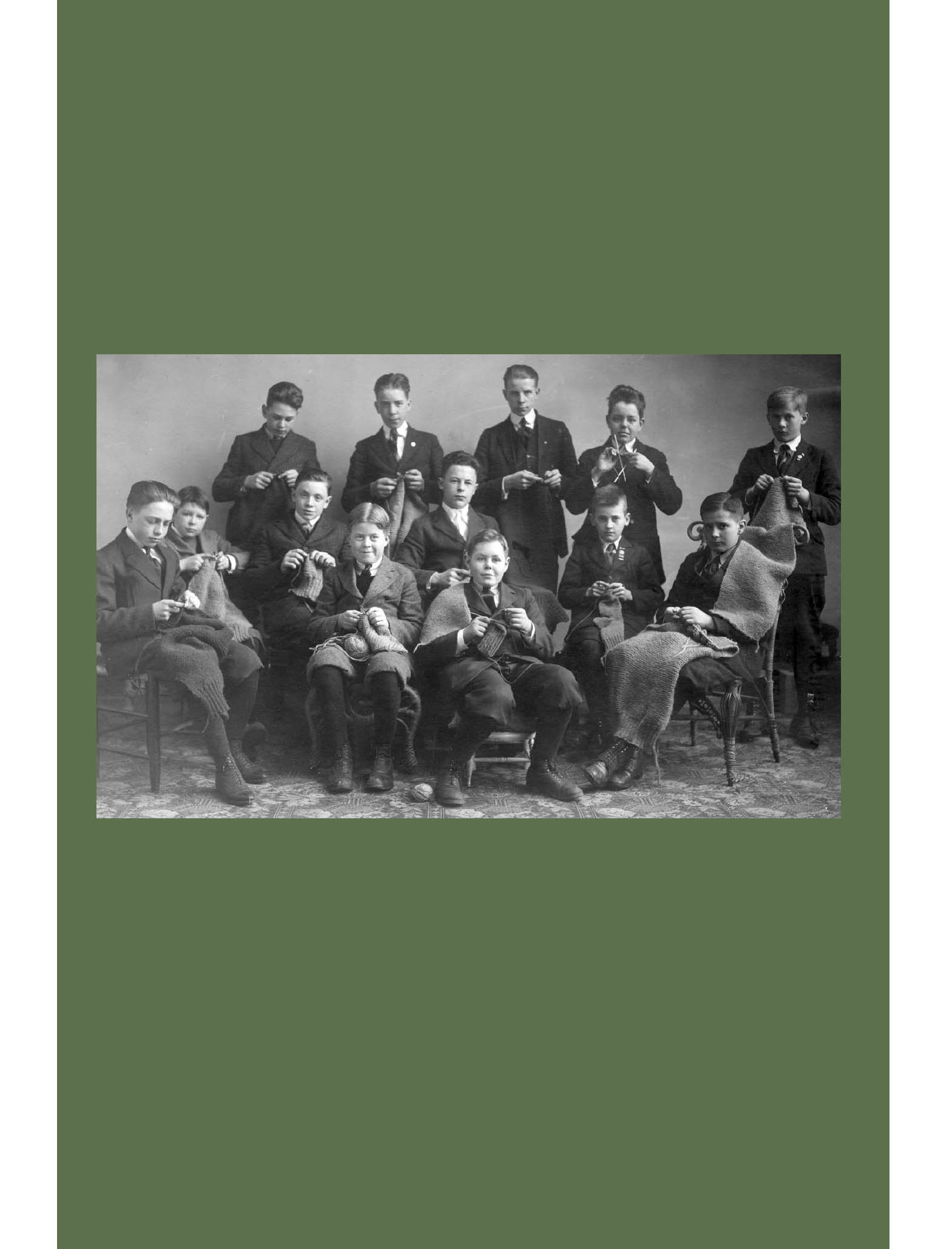

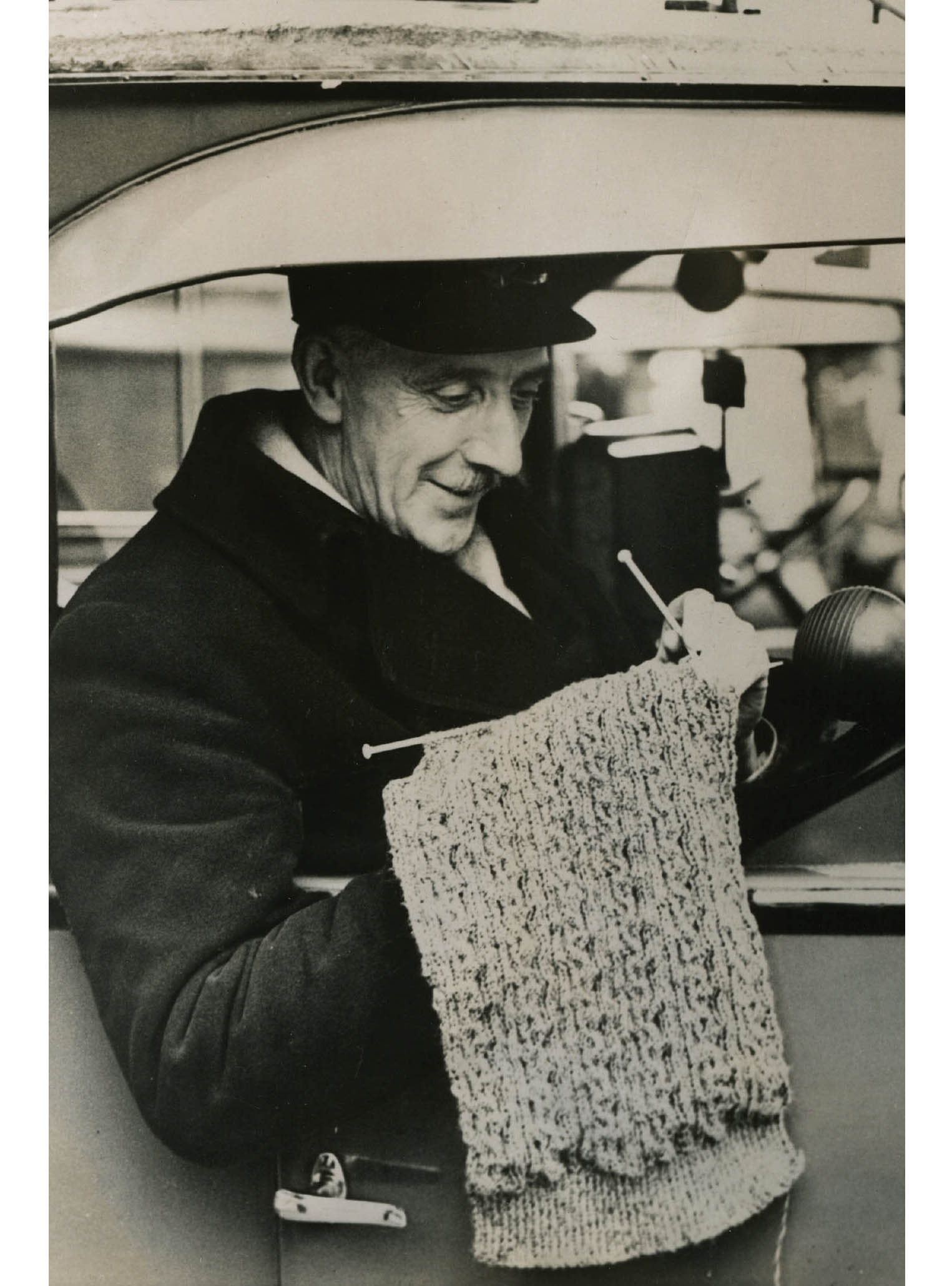

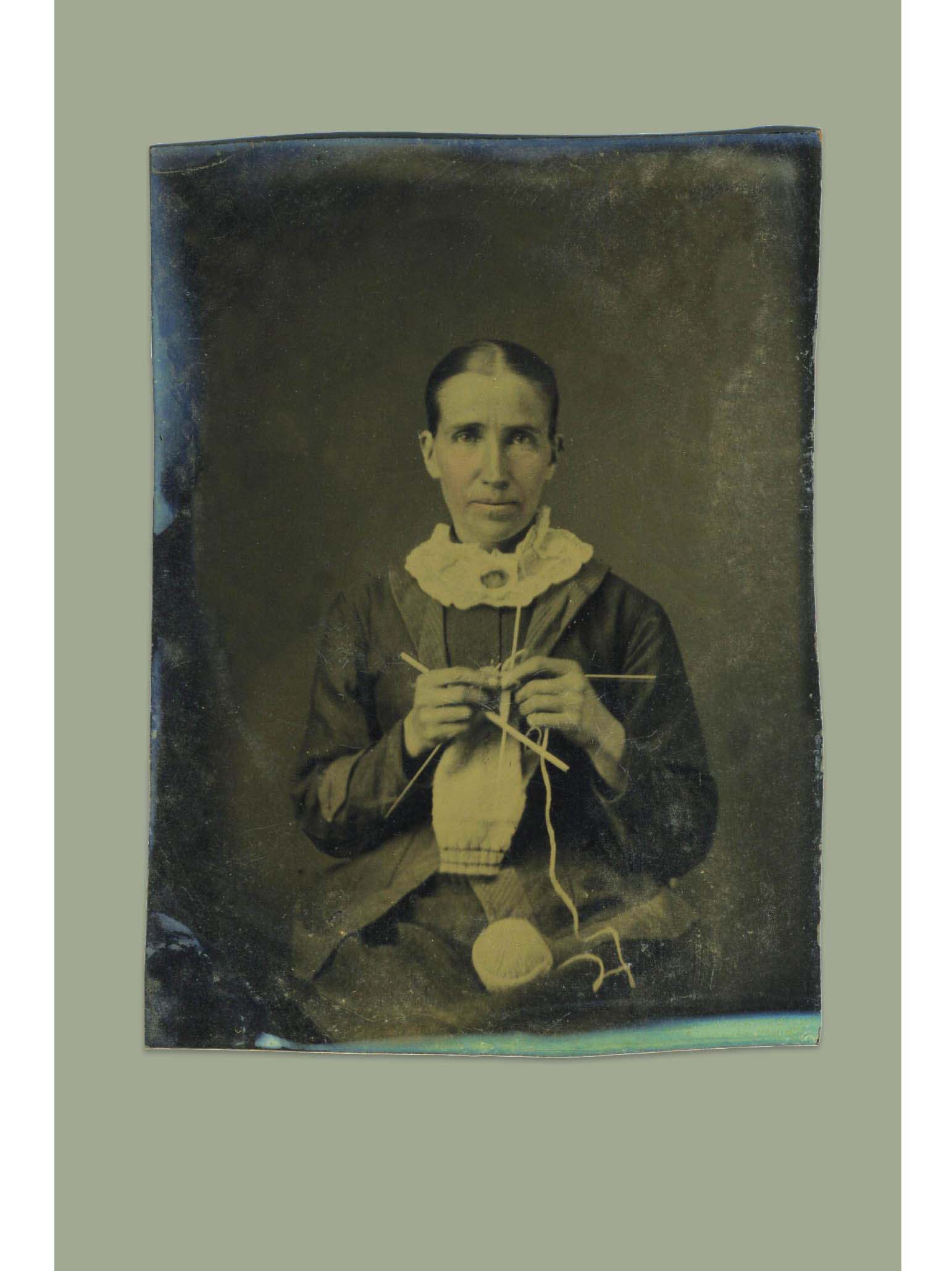

For while knitting has been around for centuries, it is only in the last 150 years that we have been able to actually photograph someonea mother, daughter, sister, brother, father, son, or friendin the meditative act of knitting. These images of knitters provide a glimpse into a daily pastime that was an unlikely subject for photography. We get to peek behind the yarn curtain, to speculate: What kinds of people liked to knit? What are they knitting? And why did they want to be photographed with their knitting? In the mid-1800s knitting wasnt just a hobby, as it often is today, but an essential household craft. When a woman was posed with her knitting in early photographs, it was an expression of her virtue and skill as a homemaker. In Victorian times knitting became fashionable among wealthy women, and many photographic portraits convey knitting as a sign of culture and artistic ability. During times of war, knittings popularity soared, and in photographs made during World War I and World War II, it is common to find movie stars, Red Cross nurses, soldiers, prisoners, and members of knitting clubsmen, women, girls, and boys of all ages and from all over the world, with their heads bent down, focused on knitting items (especially socks) for the troops.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as photography became more ubiquitous, people look more comfortable in front of the camera with their knitting. At the simplest level, the images in this book of people knitting are delightful vintage photographs we can enjoy for their individual charm as portraits, snapshots, or whimsical artifacts of bygone days. But they reward on another level, too, for they often contain a hint about what the act of knitting has meant personally and culturally at different points in history. Whether as a symbol of virtuosity (idle hands are the devils workshop)or as a gesture of wartime patriotismor to document the sitters personal idiosyncrasythese images of knitters open up worlds of interpretation, while always being, first and foremost, fun to look at. barbara levine

Knitting appears altogether mechanical, and the knitter keeps up her knitting even while she reads or is engaged in lively talk. But if we ask her how this is possible, she will hardly reply that the knitting goes on of itself.

Knitting appears altogether mechanical, and the knitter keeps up her knitting even while she reads or is engaged in lively talk. But if we ask her how this is possible, she will hardly reply that the knitting goes on of itself.

She will rather say that she has a feeling of it, that she feels in her hands that she knits and how she must knit, and that therefore the movements of knitting are called forth and regulated by the sensations associated therewithal, even when the attention is called away.  professor william james, laws of habit, popular science monthly, 1887

professor william james, laws of habit, popular science monthly, 1887

Next page

T he one hundred photographs in this book, dating from the 1860s to the 1960s, are of people knitting. They come primarily from my personal collection of vintage vernacular photographs, which I started over twenty-five years ago when a passion for old photographs took hold of me. Without fail, whenever I find a snapshot of someone knitting it makes me think of my mother. One of my earliest memories of my mother was watching her knit and listening to the sound of knitting needles constantly clicking. The combination of her intense focus on what she was doing and the rhythmic sound of her needles click, click, clicking created an air in the room that signaled something important was happening. Whenever my mother was in her knitting trance (as I called it), I knew not to interrupt her, and often I would complain: All you do is knit! I do not have a single snapshot of my mother knitting, but I do have photos of me as a child wearing many of her creations.

T he one hundred photographs in this book, dating from the 1860s to the 1960s, are of people knitting. They come primarily from my personal collection of vintage vernacular photographs, which I started over twenty-five years ago when a passion for old photographs took hold of me. Without fail, whenever I find a snapshot of someone knitting it makes me think of my mother. One of my earliest memories of my mother was watching her knit and listening to the sound of knitting needles constantly clicking. The combination of her intense focus on what she was doing and the rhythmic sound of her needles click, click, clicking created an air in the room that signaled something important was happening. Whenever my mother was in her knitting trance (as I called it), I knew not to interrupt her, and often I would complain: All you do is knit! I do not have a single snapshot of my mother knitting, but I do have photos of me as a child wearing many of her creations.

Knitting appears altogether mechanical, and the knitter keeps up her knitting even while she reads or is engaged in lively talk. But if we ask her how this is possible, she will hardly reply that the knitting goes on of itself.

Knitting appears altogether mechanical, and the knitter keeps up her knitting even while she reads or is engaged in lively talk. But if we ask her how this is possible, she will hardly reply that the knitting goes on of itself. professor william james, laws of habit, popular science monthly, 1887

professor william james, laws of habit, popular science monthly, 1887