Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to my husband, Drew, my daughter, Noelle, and my son, Miles, for their forbearance and support during this books evolution.

In addition, I am indebted to the stellar faculty of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing Program, with special gratitude to Douglas Glover, David Jauss, and Xu Xi, whose uncompromising commitment to excellence fostered my ambitions. Program Director Louise Crowley and Assistant Director Melissa Fisher (with a nostalgic nod to Katie Gustafson) infuse the entire community with a deep generosity of spirit. And to all the students (current and former) of that fine institution, my deepest thanks for the joyous experience that is being an MFA candidate at VCFA.

I wish to thank Kaylie Jones, Mike Lennon, and Bonnie Culver, the judges of the 2007 James Jones First Novel Fellowship, for choosing my manuscript from the pile of outstanding applicants, and Christopher Busa of Provincetown Arts, who published a chapter of the novel in 2008.

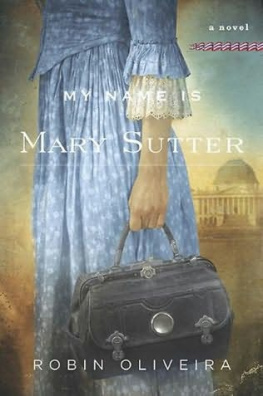

Marly Rusoff, my extraordinary agent, and her partner, Michael Radulescu, brought enthusiasm, competence, and dedication to Mary Sutter. I am a very lucky writer to have found Marly, and in turn to have been found by her. My editors, Kathryn Court and Alexis Washam, are insightful women whose eagle eyes and critical acumen drove me deeper into the story, helping me find its best and truest incarnation. The whole team at Viking has been kind and supportive.

Liesl Wilke, my dear friend, read the final manuscript and helped me unsnarl some very reluctant sentences. My husband, a physician, tutored me on the finer points of childbirth. Dennis and Kathy Hogan spent a week one winter driving me around the greater D.C. area visiting Civil War sites and museums. In addition, Domenic Stansberry read my final manuscript and made several helpful suggestions. For their words of encouragement, I also wish to thank Andre Dubus III and Wally Lamb. And finally, to Douglas Glover, an enduring and heartfelt thank-you for the gift of the question that guided me home.

People have asked me about the amount and type of research I conducted. What follows is a brief and by no means comprehensive account of an effort that spanned several years and myriad institutions and was gleaned from books, Web sites, historians, libraries, museums, and various primary documents, including newspapers, journals, government publications, lectures, and diaries. Most important, I delved into the records of the National Archives for the original documents from the Union Hotel Hospital. The Library of Congress proved invaluable for Dorothea Dixs letters and the records of the Sanitary Commissions visit to Fort Albany. The New York Public Library also provided me with additional information about the Sanitary Commission. The Interlibrary Loan of the King County Library hunted down book after book and untold amounts of microfilm reels for me. The Special Collections at the University of Washington Medical School Library holds a plethora of books on medicine and midwifery that I plundered. I made heavy use of the New York Timess online archives. I would also like to note the Son of the South Web site for posting issues of the magazine Harpers Weekly.

A number of researchers steered me toward some invaluable discoveries. I am especially grateful to the online librarian at the Library of Congress who directed me to Clara Bartons War Lecture, which provided firsthand documentation of the aftermath of the Second Battle of Bull Run and South Mountain. I hope Miss Barton wont mind that occasionally I used her specific details; they captured the peril under which the men and women at Fairfax Station and South Mountain were working, particularly her fear of the candles catching the hay on fire and her conversation with a surgeon who intimated that triage occurred after the battle. The inimitable Miss Barton also was at Antietam, but there we parted ways. I relied mostly on my imagination and on Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign by Kathleen Ernst.

Other books of great help were Civil War Medicine by C. Keith Wilbur, M.D.; all volumes of the Pictorial Encyclopedia of Civil War Medical Instruments and Equipment by Dr. Gordon Dammann; A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, July 1-November 20, 1863 by Gregory A. Coco; Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace; Mr. Lincolns City by Richard M. Lee; Loudonville: Traveling the Loudon Plank Road by Sharon Bright Holub; Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt by Herman Haupt; and Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War by George Worthington Adams. The Personal Memoirs of John H. Brinton, Major and Surgeon U.S.V., 1861-1865 detailed for me some of the history behind the founding of the Army Medical Museum, which eventually became the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Also, his captivating observations about battlefield rigor mortis enlivened the aftermath of battles more than almost any other detail that I read. The six-volume Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, first encountered at the National Archives and later through interlibrary loan, provided critical medical information. My special thanks to the Journal of Forensic Sciences, Volume 51, Issue 1, pages 11-17, The Effects of Chemical and Heat Maceration Techniques on the Recovery of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA from Bone, for the methods and list of chemicals that might have been employed to skeletonize bone.

Historians and rangers at the National Parks of Gettysburg, Antietam, Fords Theatre, and Bull Run were helpful not only with verifying obscure points of history, but also in directing me toward primary documents that proved pivotal, especially Herman Haupts memoir. Frank Cucurullo at Arlington House not only educated me as to the significance of the site, but also read a chapter of the book and made suggestions. The director of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland, George Wunderlich, spent time on the telephone with me early on in my research. I am also grateful to Terry Reimer, director of research at the museum, for her generosity. In addition, the museums exhibits helped in visualization of battlefield care. Also, the National Museum of Medicine at Walter Reed has a wonderful Civil War exhibit. The Albany Institute of History and Arts archives yielded critical information on nineteenth-century Albany. To Erin McLeary, Michael G. Rhode, Brian F. Spatola, and Franklin E. Damann, curator, Anatomical Division, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, thank you for helping me track down information on bone preservation. Special thanks to the Town of Colonie historian, Kevin Franklin, for information on Irelands Corners, or Loudonville, as it is currently known. And to Kathy Sheehan of the Rensselaer County Historical Society, thank you for walking me around the historic district of Troy, New York. Many thanks to James Dierks of the New York Museum of Transportation for answering my questions regarding transportation speeds in the nineteenth century. More thanks to Martha Gude, Roger S. Baskes, Joan R. McKenzie, and Jane Estes.

When I read in Louisa May Alcotts account of her brief tenure at the Union Hotel Hospital in January of 1863 that a rat had nested in her clothing and stolen even the meager amount of food that she had purchased at a corner grocer and set aside for herself in hope of augmenting the paltry army hospital diet, I knew I had a view into the destitute conditions under which both the nurses and patients were suffering. I acknowledge that I was perhaps a bit hard on Dorothea Dix, though I believe I portrayed her as she was perceived at the time. I am happy that history has revealed her courage and independence.

I am deeply grateful to my husband, Drew, my daughter, Noelle, and my son, Miles, for their forbearance and support during this books evolution.

I am deeply grateful to my husband, Drew, my daughter, Noelle, and my son, Miles, for their forbearance and support during this books evolution.